ILLINOIS, USA — A little-known, government-sponsored war was fought across Illinois during the 1930s and '40s, the enemy of which can still be heard on chilly winds to this day

Bombing squads were deployed. Explosions splintered trees and blew off body parts. Blood and guts periodically rained down.

The war was waged not on hostile humans but on perceived avian adversaries. Millions of dollars were spent to defeat the enemy, all for the state to ultimately lose the war. The conflict would even be lost to time, with even the Illinois Department of Natural Resources telling 5 On Your Side they had no record of the bombing campaign.

5 On Your Side uncovered the truth of the battles, and why they were eventually ineffective.

Illinois' crow war: Bombs used to blow up 'feathered gangsters'

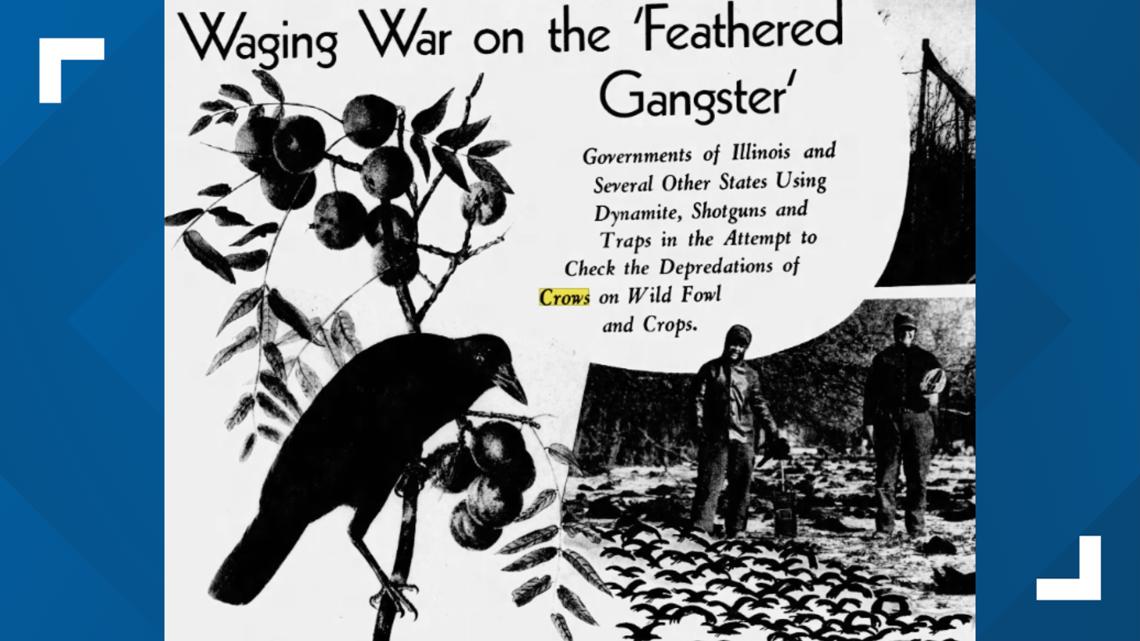

Millions of crows called Illinois home during the winter months, to the dismay of area farmers. The birds were accused of damaging farm crops and preying on song and game birds throughout the state. They were even demonized in the local newspapers, including an article in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch about an anthropomorphized duck named "Susie."

"Out of the sky swooped a group of black furies, yelling hoarsely. Sharp black bills assailed Susie, striking fiercely at head and eyes ... In a few moments the raiders were soaring away, and with them went the eight greenish eggs ... Quaking her anguish Mre. Mallard watched the departure of her offspring that would never waddle down to water," the article written by Keith Kerman said.

The angry voices were loud enough to get the attention of officials from the then-Illinois Department of Conservation, a department that has since merged with the IDNR.

In response, conservation officials would spend years experimenting with dynamite bombs for a blitzkrieg on roots, or large gatherings of crows who huddle together for warmth. They reportedly "perfected" a killing machine.

"Frank N. Davis, inspector in charge of predatory control, ... is said to have perfected one that is less expensive than those used several years ago and also more effective," according to a 1940 article in the Belvidere Daily Republican. "It's a cylindrical cartridge about 10 inches long and two inches wide, containing an eight-inch stick of dynamite ... (surrounded by)two and one-fourth points of No. 6 1/2 steelblast shot and bits of broken metal."

Officials would set the bombs off in trees where the crows would roost, each one killing between 3,000 to 20,000 birds in a single blast.

One campaign in Decatur involved setting off 110 bombs, killing enough crows to fill "several haywagon loads," according to a 1939 Herald and Review article.

TIME Magazine reported conservationists set off 180 bombs near New Berlin in 1939, which killed an estimated 30,000 crows.

"There were crippled crows around here for the longest time after (the bombing)," said Pitman farmer Bert Aikman while recalling the bombing campaign during an interview in the 1970s. "They would have a wing shot off or a leg shot off."

Why Illinois lost the crow war

IDNR declined 5 On Your Side's request for comment regarding the crow bombing campaign and details on why it ended. However, similar crow bombing campaigns in other states, and their lacking results, shine a light on why Illinois officials stopped the practice.

Despite the vast death and millions of dollars spent attempting to eradicate the bird, the crows persisted. In fact, when the smoke settled, all of the bombs didn't even make a dent in the total population. It may have actually made matters worse for local farms.

USDA Ornithologist Richard Dolbeer studied the bombing and killing of 3.8 million crows in Oklahoma between 1934 and 1945 and wrote about the results in a chapter of "Ecology and Management of Blackbirds (Icteridae) in North America." No evidence showed that the explosions had any long-term effect on crow population levels, agricultural damage, or waterfowl production.

Other evidence would suggest bombing crows actually increased crow populations in the long term. Writer Mary Roach, in her book "Fuzz: When Nature Breaks the Law," uncovered USDA oral history transcripts detailing a phenomenon called "compensatory reproduction."

"Destroy a chunk of the population, and now there's more food for the ones who remain," wrote Roach, describing the phenomenon. "Through a variety of physiological responses - shorter gestation periods, larger broods, delayed implantation - a well-fed individual produces more offspring than one that's struggling or just getting by. With ample food, both the well-fed parents and their well-stuffed young are more likely to produce."

It's most likely not the fault of the modern IDNR that it no longer has documentation of why the practice of crow bombing ended in Illinois, let alone was allowed to begin in the first place. The practice has long been discredited and largely abandoned due to numerous factors including labor, expense, hazards involved and a lack of effectiveness evidence.

In the end, the Illinois Crow War acts as yet another example in the United States' often inside-out history of conservation.