ST. LOUIS — Sheila Forrest boarded a plane from California to St. Louis as soon as she heard the coronavirus had hit the Midwest.

Her parents, both in their 80s, live here, and she said she was “terrified” of what could happen to them if they contracted the disease.

And, as much as it pained her, she knew she had to shut down the family business, Afro World, during its 50th anniversary year.

The business began when Forrest’s father, Russ Little Sr., started losing his hair and needed a toupe made for a black man and couldn’t find one to his liking.

So, he made his own.

He got so many compliments on it that he eventually quit his job as an engineer for McDonnell Douglas and founded the family business. In addition to toupes for men, the business expanded into hair extensions for women as well as African-inspired merchandise, including clothing, jewelry, artwork, greeting cards, games and other goods.

“We call ourselves the keepers of the culture,” she said.

Telling the staff to go home without knowing when or if they would ever be back was devastating, said Sheila Forrest.

She left California in such a hurry that she forgot to bring face masks home for her parents.

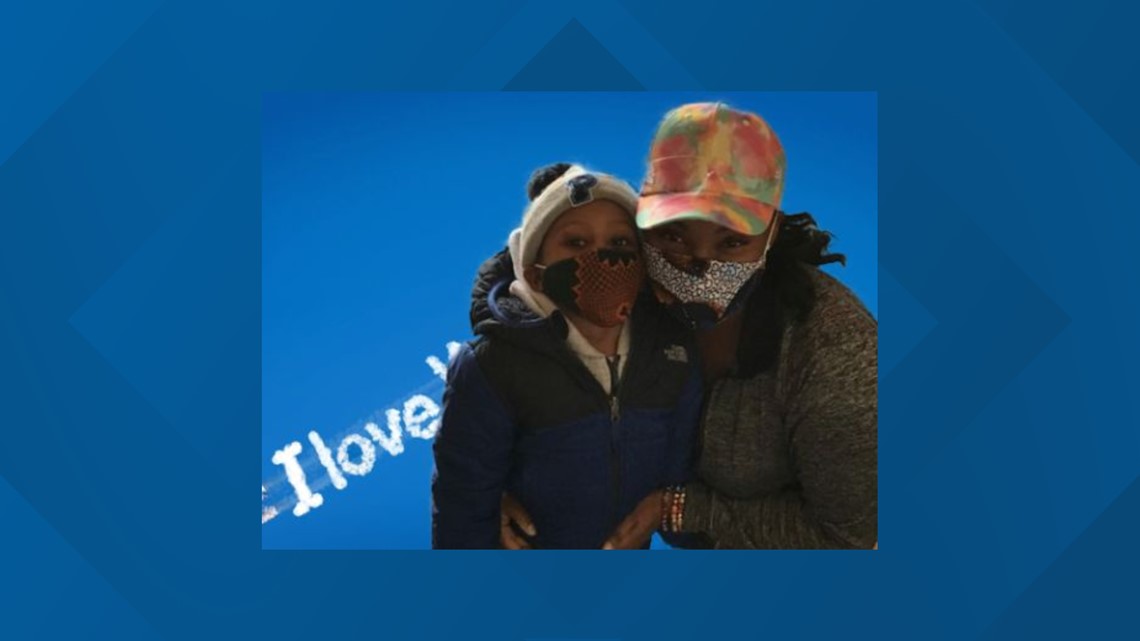

She called one of her clothing vendors, asking if they could make some face masks out of their African-inspired fabrics for her parents. They said they could only do a bulk order, so she posted pictures of the extra masks on the store’s social media pages saying they were available.

“It just exploded,” she said. “We couldn’t keep up.”

That was about three weeks ago, and Afro World has now become a mail-order only business selling African-inspired cloth facemasks.

Sheila Forrest is not allowing the store’s employees to come back to work, so even though she's the president of the company, she’s filling all of the orders in the store by herself.

"Let's not get caught up on titles," she quipped. "You might as well call me the janitor at this point because I'm doing it, too."

She estimates that she’s been sending out 100 to 200 masks daily for $15 each. And they’re being sent all over the country, she said.

She said she hopes the newfound niche will help keep the business afloat so the employees will have jobs when the pandemic ends.

“We are a business,” she said. “We have to survive. And we have bills to pay.

“We have to create our own stimulus. As much as I would love for the government to send me a check, it’s not going to happen for all the businesses. It makes my heart really feel sad to know that the foundation of this country isn’t going to have a lot of small mom and pop businesses because I don’t know how they’re going to survive this.”

The building where the store now stands used to be a bank, so the drive-thru window is still intact.

Forrest was using it to sell masks to customers. She put them in plastic bags. Handled them with gloves. Wore a mask herself. And accepted payment only over the phone to avoid touching anyone’s credit cards.

Most of those who came through were elderly. She could see her mother’s face in theirs. Scared. And unprepared, having no masks of their own.

The drive-thru window is quiet for now.

St. Louis County counselors sent her a letter ordering her to shutter the business because they had received a complaint that she was not adhering to essential business restrictions. Her brother, Russ Littlr Jr., the business’s technology coordinator, was furious about the county’s counselor’s actions, saying they based the notice on a complaint that came from the county’s website without doing any investigation.

“They sent us a cease and desist letter based on no evidence whatsoever,” he said. “What level of due process is that?”

Even though she said she believes her set-up was sterile and that selling facemasks to people in the underserved north St. Louis County was an essential service, she is not taking any chances.

Now, the business is mail-order only. But, she added, county counselors have since approved of the mask-selling operation and "acted immediately, because they knew of the need in our community."

“I could have a five-year plan and it would never included a pandemic,” she said. “I could never have saved enough money for this. You have to keep all avenues open and take one moment at a time.

“This is our stimulus. Hopefully, we will be here another 50 years.”

But she also knows, eventually, the pandemic will end. And people won’t need masks anymore. They will need jobs – many of which won’t be there, which means they will have less to spend on the goods at Afro World.

“I don’t know what the future is,” she said. “I don’t know what it’s going to look like for us on the other side of this thing.”

For now, it is one mask at a time.