ST. LOUIS — Many families can access centuries of history over hours, days, weeks and months, but two women have spent nearly 50 years trying to scratch the surface of just one century.

Brenda Huddleston, 74, and Janice Griffin, 72, are first cousins born and raised in St. Louis. The pair, affectionately known as “sister cousins," have spearheaded the blanks of their family tree which appears to be loosely documented and widely neglected.

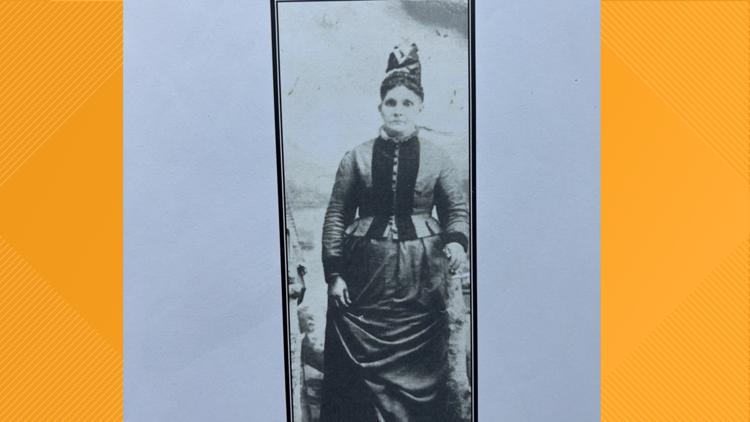

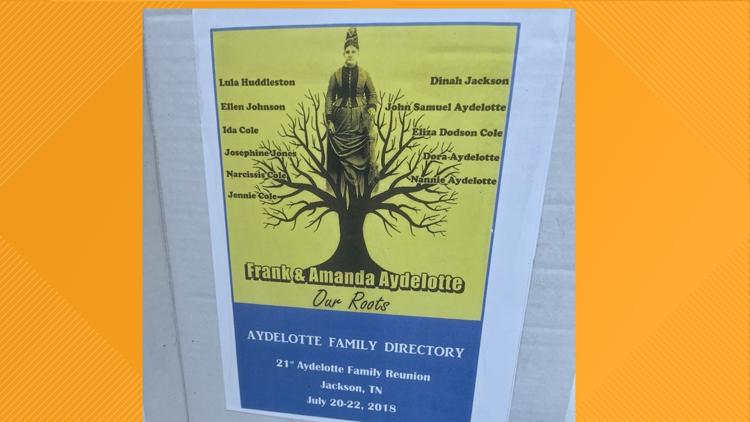

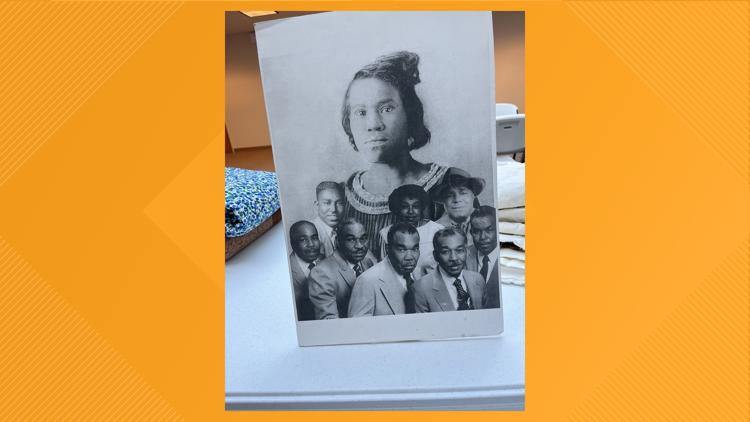

They have since found enough evidence leading them back in time to 1845 on a Memphis auction block where their ancestor, Amanda Aydelotte, a biracial slave previously owned by a St. Louis doctor, was sold for $1000. She is Huddleston and Griffin's great-great-great-grandmother.

The sister cousins have gone to great lengths to verify what information they have heard through oracles over the years, and along the way, they have woven together a tapestry linking their futures to their past.

The power of oral storytelling

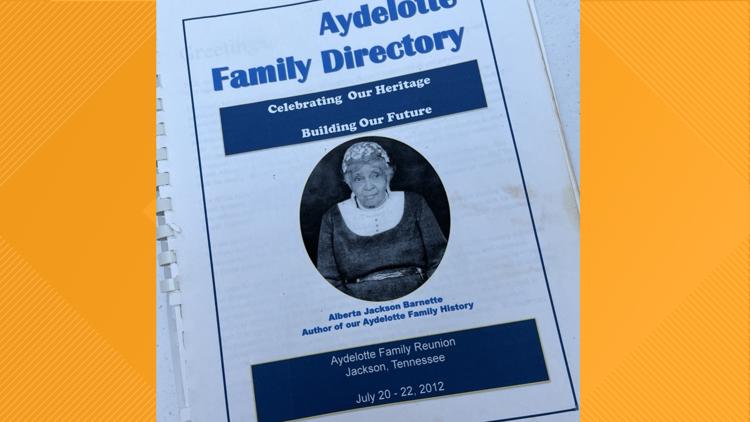

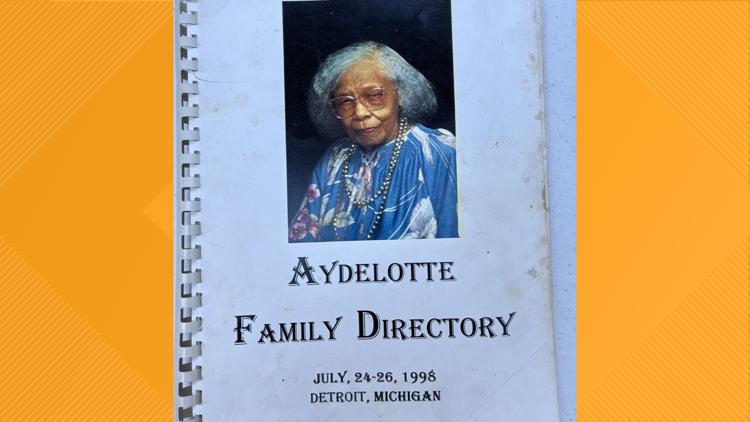

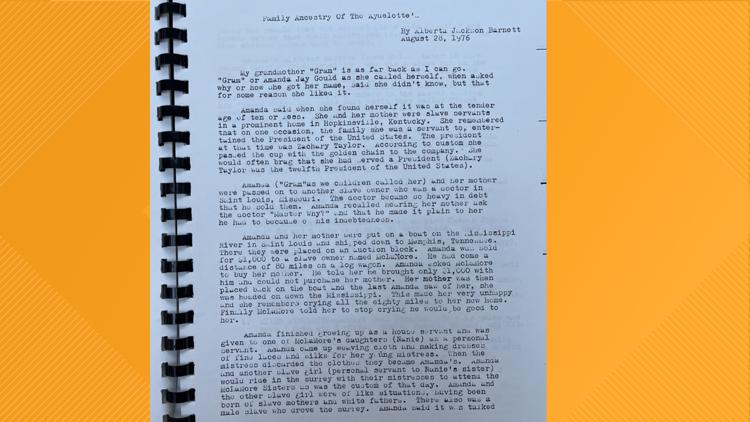

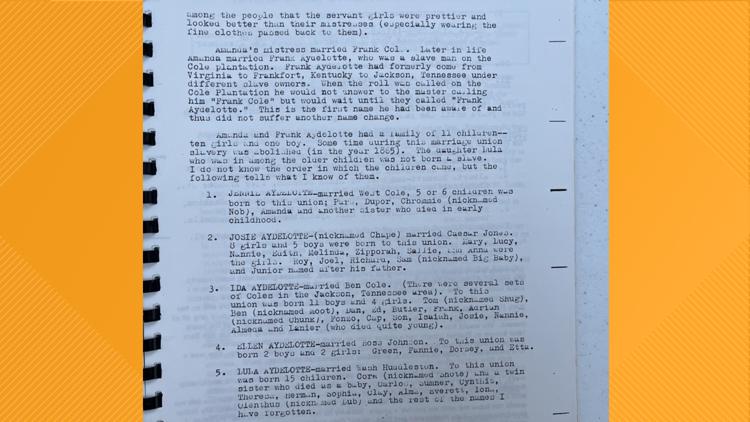

The road to uncovering history began in 1976 during a family reunion in Memphis. That's when their cousin Alberta, granddaughter of Aydelotte, shared a written copy of the family's history from memory. The holes in Alberta's story ignited a curiosity.

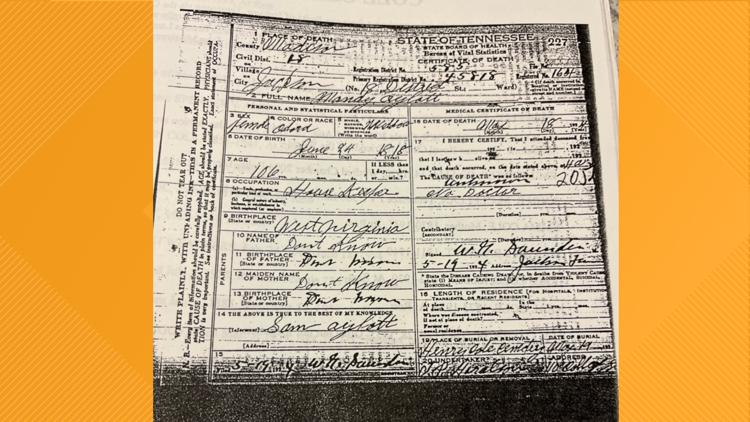

It is known that Aydelotte shared stories from her life with her 11 children. According to her death certificate, she lived until she was 106 years old, which means grandchildren and great-grandchildren heard her talk about her life as a slave.

"Stop crying! I'll be good to you" are the words Sugar McLemore, Aydelotte's first slave owner in Memphis said, according to her granddaughter, when she realized she was going to be taken from her mother at just 10 years old. When Aydelotte asked McLemore to buy her mother, he replied that he did not have more than $1,000. Therefore, it is highly possible that Aydelotte never saw her mother again.

Huddleston and Griffin started their search with the elders in their family, who by the 1970s and 1980s were also the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of Aydelotte.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, 80% of African Americans were illiterate in 1870. However, Aydelotte still passed down stories, and when the 1900s rolled around, 44% of African Americans were still illiterate.

For many African Americans, this was the only way to pass things down. The tradition lived in Huddleston and Griffin's home as well as they can recall hearing stories about their ancestors and elders throughout their childhood.

According to Pew Research Center, 76% of African Americans learn about their family history from their relatives.

"They held it," Huddleston said. "Family was important to them so they held on and they shared. We had to go to the houses and sit down and listen, and listen, and listen to get the information that we needed."

"A lot of times that history is very painful," Griffin said. "Imagine cousin Alberta listening to her grandmother Amanda telling her about how she was sold, how she was separated from her mother. Those stories are painful for them."

When the "sister cousins" ran out of information from the family, they began to look outward at the U.S. Census records, landowner records, marriage licenses and libraries, and they managed to find a journal that belonged to Aydelotte's slave owners.

"There are a lot of resources," Griffin said about how much time has changed since they began this feat. The pair now belong to several genealogy groups online.

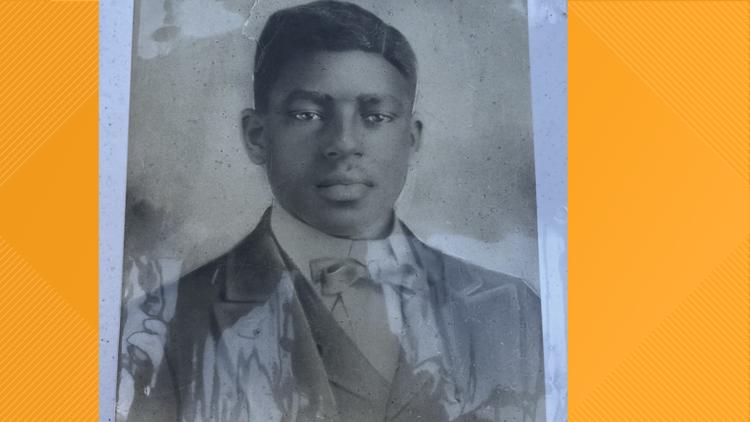

The research has given the family proof of the slave owner who purchased Aydelotte, the slave she married - who was also a slave on McLemore's plantation - Frank Aydelotte, and even the overlapping names of children recorded between the McLemores and Aydelottes.

"Janice and I would go to the library along with a few other cousins, and it would be so aggravating because you hear other people say, 'Oh, I found such and such,' but it's never us," Huddleston said. "So as a result of that, it's just so important to have that information for generations to come."

"I always say if I could title a book, it would probably be, 'Where are my people, who are my people?'" Griffin said.

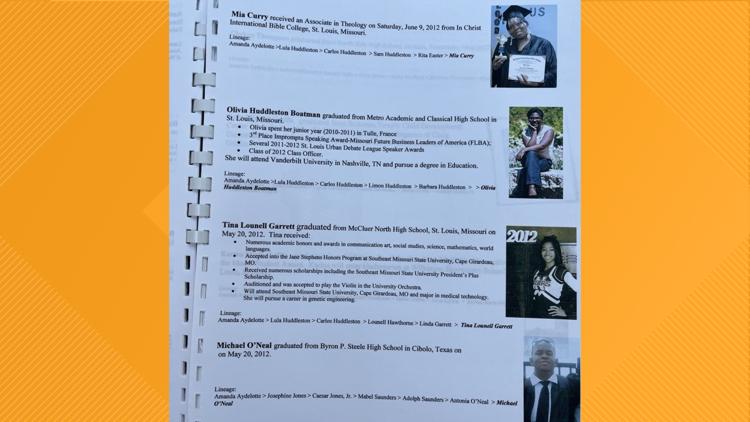

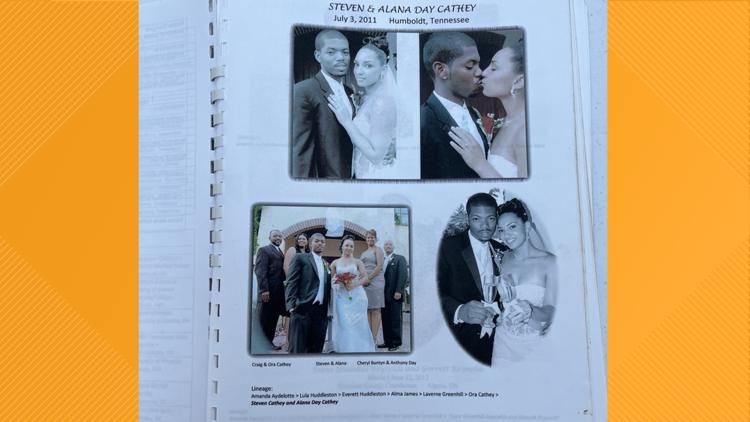

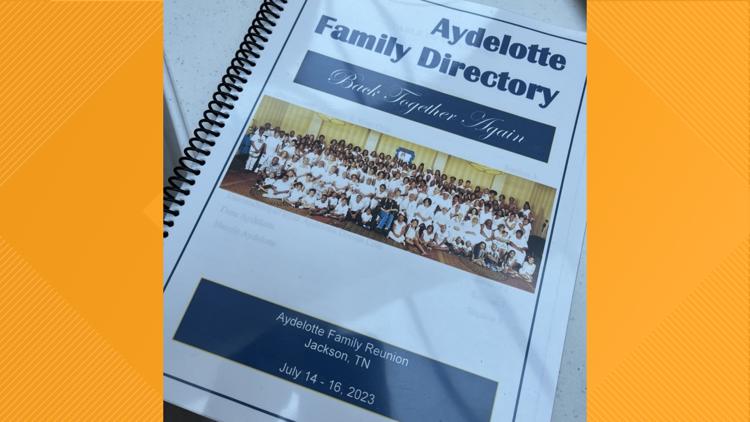

Through their extensive research, the pair have been able to find living descendants from all 11 of Aydelotte's children through birth and death certificates. As technology has advanced, they have been able to link over 5,000 living and deceased decedents to Aydelotte using Ancestry.com.

Huddleston and Griffin also learned through oracles that Aydelotte was a midwife.

"We've heard different ones say she delivered this baby or that baby," Griffin shared." I found documentation where it listed the birth of one of her grandchildren and it said, 'midwife Amanda Aydelotte.' That was confirmation."

On the rare occasion when the pair would find any clue that aligned with the oracles, they celebrated together.

"We've got it! We've got it." Griffin said enthusiastically, savoring her latest discovery.

But that’s not the only thing Aydelotte passed down.

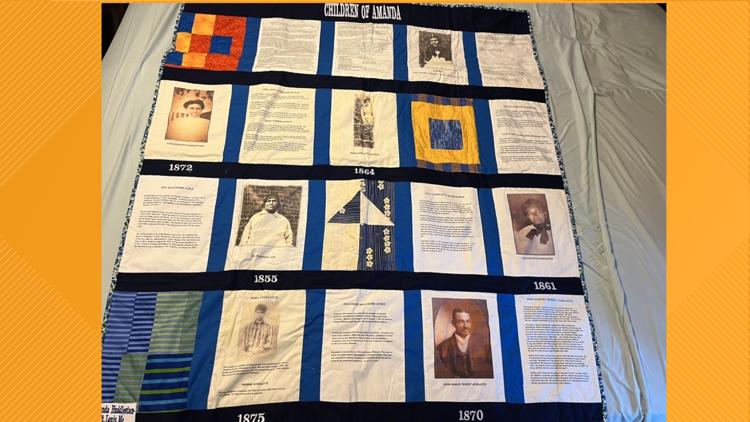

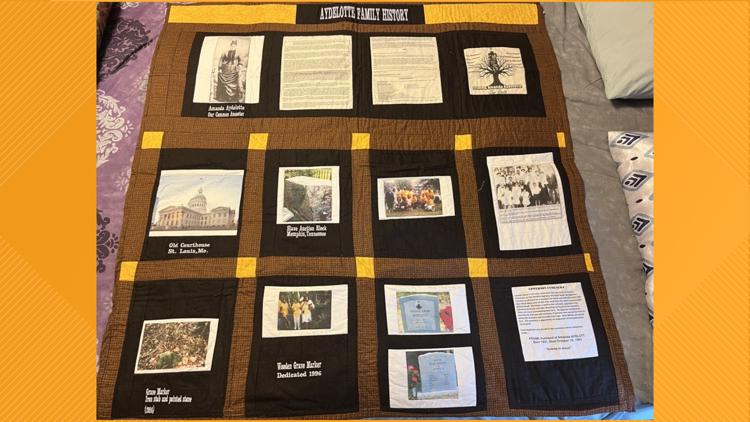

The quilts

Aydelotte was also a seamstress, according to Huddleston and Griffin's oracle data.

"I grew up looking at my grandmother and mother quilt every winter," Griffin said.

Huddleston recalls making her first quilt outside at 8 years old on the porch.

"We can see a lot of her in us," Griffin said.

"We're not fragmented people. We're very communal people, and the parts of our lives are interconnected," said the Rev. Dr. Paulette Sankofa, a mixed-media artist." What a blessing that would be for them to see that they are still here through us."

She has decided to contact the History Museum on behalf of Aydelotte's family, all thanks to Huddleston and Griffin's discoveries.

Sankofa did her doctorate on African-American elder women's resilience. She has spent her career focusing on helping others tell their story and leave their legacy.

"Developing a love for fabric you develop it on a lot of different levels because it's a visual you can see the colors, you can see the pattern," she said. "... You kind of get a vision of what something can become because I always say when I make something, I ask the fabric what it wants to be. So like do you want to be an image of somebody, do you want to be some fruit? What do you want to be? Because in your mind it's not an immediate translation like an orange for an orange. It's where you see something beyond what it is, and the fabric kind of helps you dictate that. It's kind of exciting for me. Sometimes, I make things right away, and sometimes, I just wait and ruminate over it."

Much like the fabric in Sankofa's hands, the "sister cousins" seem to be led by the stories they've received throughout the years.

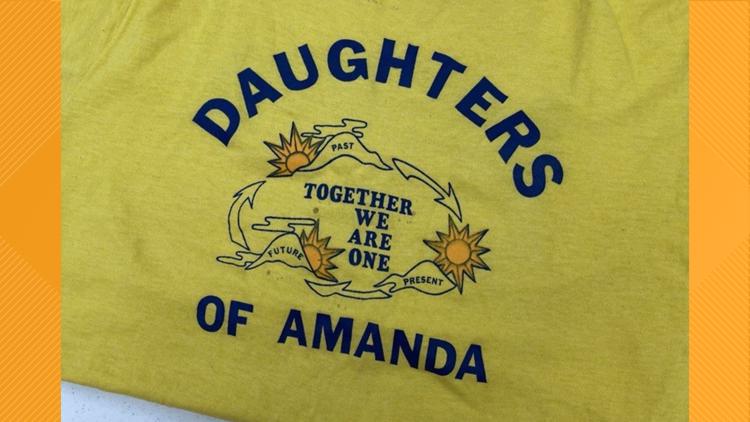

The pair took their needlework a step further when they decided to make family quilts. One of the reasons the quilts are so large is because those who quilt in the family commit to creating nine patches, and then once each portion is completed, all of the portions are threaded together. When a family member who has contributed to the quilt dies, they take a piece of the quilt and bury it with the family member.

"In West Africa, it was men that created fabric and still do ... When that got transferred to America it didn't happen, and I expect it's because of the division of labor. Men were now expected to do other types of things," Sankofa said. Back in Africa, "they were in societies where women did a lot of planting and growing, and men made fabric and did other types of things that were protections and covering for their family."

In America, needlework continued through women like Aydelotte.

A quilt is a love note, Sankofa said. It is also evident that Aydelotte passed down those love notes.

"I developed my own research method of critical womanist ethnography and how stories are captured, how stories are told and what you have to do with them that is critical work. Because once I discovered something in the midst of finding out about a story, I have to do something about it," Sankofa said.

The sister cousin's findings

The brick wall

The obstruction in the African American lineage is called a "brick wall" in the world of genealogy. According to the National Genealogical Society, the enslaved people were not added to the federal census by name until 1870. Before that time, the slaves were documented by sex, age and tick marks.

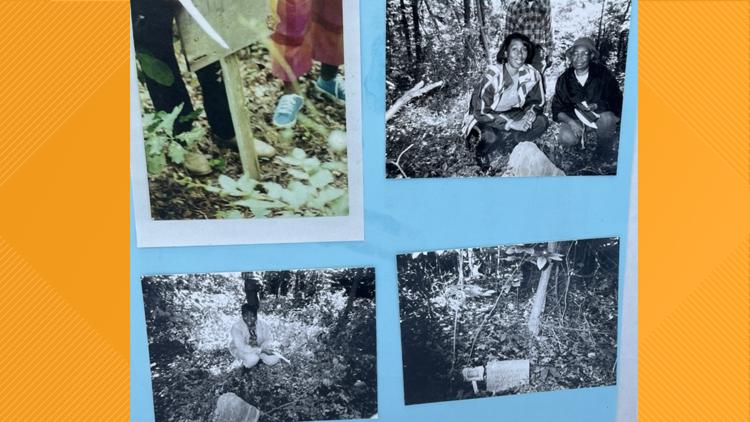

The sister cousins have tried to contact descendants of McLemore, the slave owner that bought Aydelotte, and although they found proof of the purchase, they have been unable to learn more.

"I can probably tell you more about his family (the McLemores), and that's not unusual for Black people doing research," Griffin said.

"The brick wall is being able to find and cite those sources," Griffin said. "You don't withhold information, and sometimes in just that sharing, there is a common thread or spark, and they can take that spark and build on it."

Now, the "sister cousins" have set their sights on learning more about Aydelotte's mother. After all, "on the backs of these people, you have what you have," Huddleston said.

"There is someone somewhere who knows a little bit about Amanda and her mother," Griffin said. "And somewhere in Kentucky because Amanda and her mother were servants in a prominent family before they came to St. Louis."

Aydelotte told her children stories of serving President Zachery Taylor with a cup that had a gold chain.

"That's that huge brick wall," Huddleston said.

For generations to come, these sister cousins have become a resource for their family and have left documentation for the seed of the free.