ST. LOUIS — For Kiku Obata's father, building a life in St. Louis started at the drafting table.

"How interesting it must have been for my dad to come here," said Obata. "He wanted to be an architect from when he was six years old,"

Eventually, it meant building the city itself.

"Priory Chapel and the planetarium are some of my favorite projects of my dad's," said Obata.

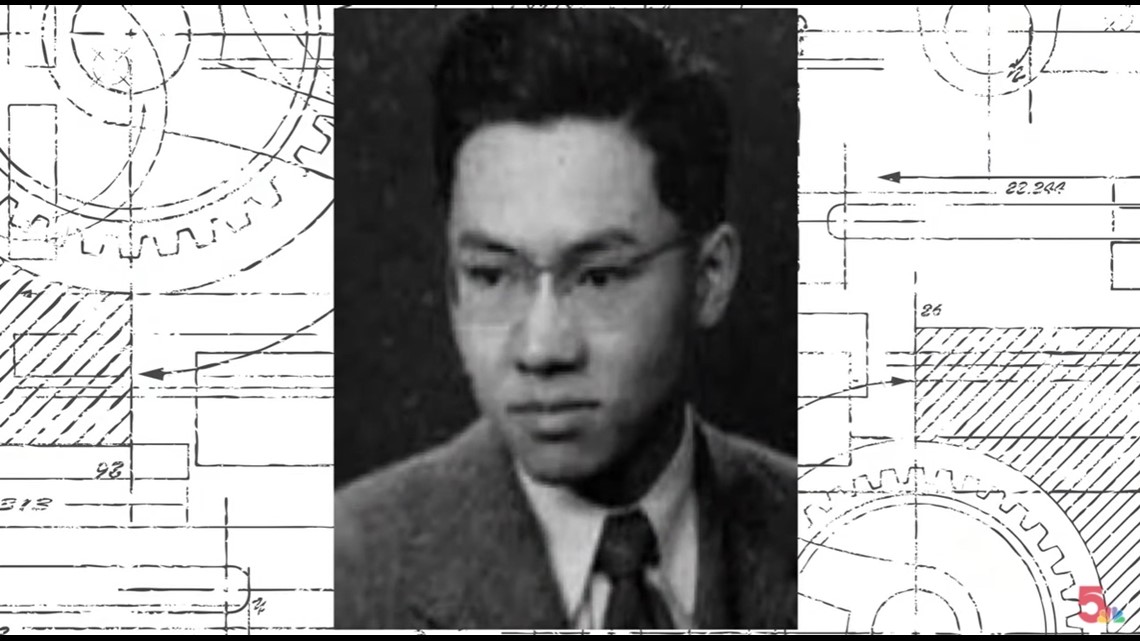

Gyo Obata was among the city's most celebrated architects. He died in March 2022 at age 99.

His daughter now runs a design firm, but St. Louis wasn't the original plan for the Obata family. Kiku's grandfather and grandmother both came independently from Japan, and Gyo was born in San Francisco in 1928. Gyo was a freshman architecture student when the Japanese military bombed Pearl Harbor. Ten weeks later, Executive Order 9066 gave the U.S. military the authority to send people of Japanese descent, living along the coast, into concentration camps.

"Most of the people lost everything," said Obata. "They had all their property."

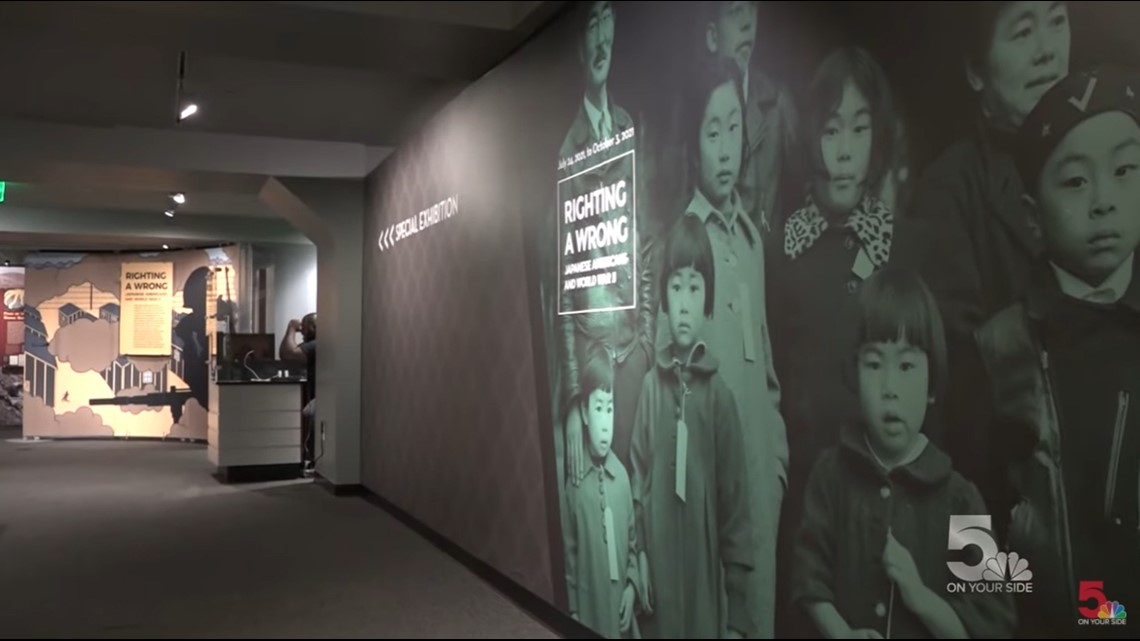

It's the focus of a traveling Smithsonian exhibit, which came to life in 2021 in the Soldiers Memorial Military Museum in downtown St. Louis. It takes a look at the years of internment when 120,000 Japanese residents and American citizens were forced to live in camps under the watch of the U.S. government.

"Imagine being forced to just walk away from everything that you've built your whole life," said Mike Venso, who is a curator for the exhibit at Soldier's Memorial Military Museum. "They had to leave behind their homes, their vehicles, their jobs, and their businesses."

One of the walls tells the story of Gyo Obata.

"He had his head down and was studying, and my grandfather said, 'Look at this political situation. You really should try to get out of here,'" said Kiku.

So Gyo applied to Washington University in St. Louis. He was accepted.

"And then a few nights later, one of my grandfather's friends, who was a colonel in the army, came to the house and said, 'Here's a pass to get out tonight on a train if you've been accepted.' So my dad left that night, and the next day everybody was rounded up to go to internment camps. It's a crazy story," said Kiku. "I mean, you just can't even imagine that happening, you know, in the United States."

It was an unimaginable reality that some are just beginning to grasp 80 years later.

"We hope that visitors to this exhibit walk away with a better understanding of what happened, what we as Americans are capable of, and hopefully learn some lessons about the consequences of our choices," said Venso.

Gyo Obata and HOK were remembered for the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, U.S. Olympic Fieldhouse in Lake Placid, home to the 1980 Miracle on Ice, Priory Chapel in St. Louis, and many more designs.

Internment was a foundational moment in history, even for those who escaped it.

"He always just loved St. Louis and has always felt he could make a difference here," said Kiku. "He felt indebted to St. Louis because of what hospitality it showed him."

Those who lived through it were sent home at the end of the war, with $25 bucks from the US government. An apology came decades later.