ST. CHARLES COUNTY, Mo. — Earl Cox sucked the air out of a St. Charles County courtroom Thursday.

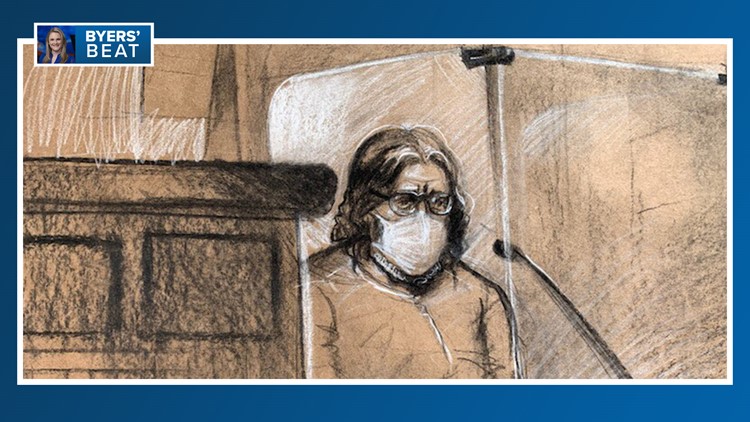

First, his walker appeared in the doorway where inmates enter. His pale white hands gripped its handles and an orange jumpsuit draped over his frail frame.

He shuffled toward his public defender, and somewhat awkwardly plopped into his seat -- as if his body were too weak to support him without his walker.

His dull dark grey hair fell just beyond his shoulders and curled at the ends. Wisps of white hair framed his face.

His white beard jutted below the surgical mask he wore. His dark brown framed glasses almost hid his deep-set eyes.

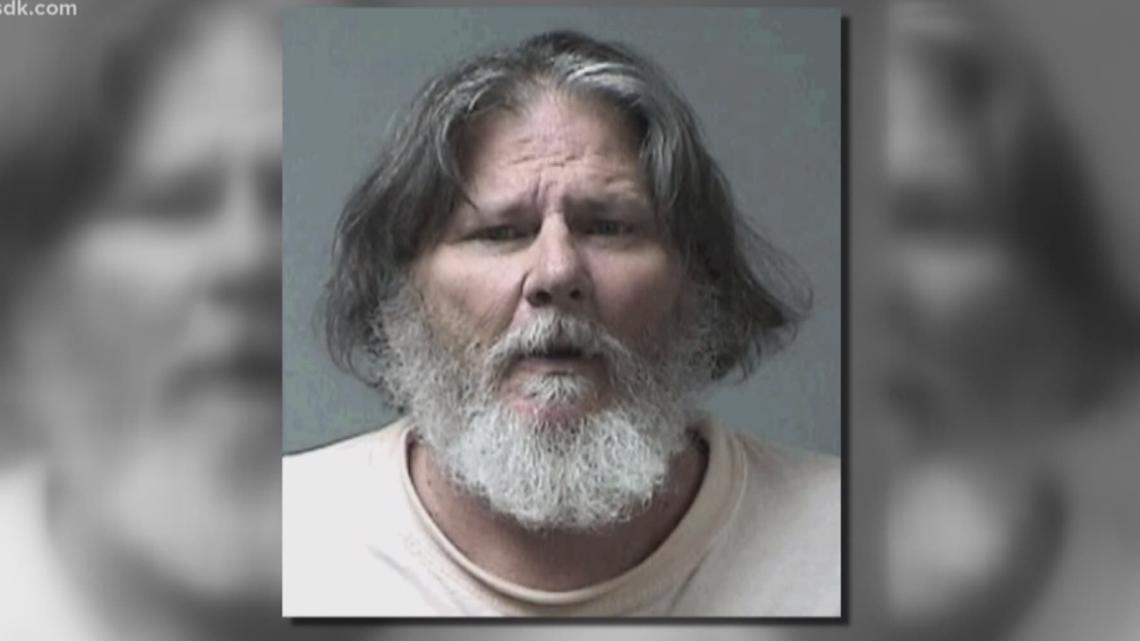

He had lost weight since his mugshot was taken during his 2019 arrest for the 1993 abduction, sexual assault and murder of 9-year-old Angie Housman -- a case that sat unsolved for 25 years and gripped the community in fear.

He looked well above his 63 years.

For one hour and 40 minutes, he answered questions from Judge Jon Cunningham – who agreed to sentence him to life in prison without the chance for probation or parole for Angie’s murder.

St. Charles County Prosecutor Tim Lohmar struck a deal with Cox that would allow him to spend the rest of his life in prison – and not face the death penalty – should he admit to the crime.

Most of what Cox said consisted of, “Yes sir,” in response to the judge’s questions.

When he spoke, he sounded like a 90-year-old man who wasn’t wearing his dentures.

But there were a few times he went beyond the two-word response.

“Do you believe your mind is clear?” Cunningham asked, to ensure he was not under the influence of any drugs or alcohol as he was pleading guilty.

“As much as it’s capable of being,” he said.

Cunningham methodically read through every piece of the facts of the case that Cox admitted to, but ad-libbed at times.

Cox told the court he had never seen Angie before she got off her school bus on Nov. 18, 1993. He had pulled to the side of the road about a half block from Angie's St. Ann home because he was having car troubles. At that point, he was already a convicted serial child predator, having been released from prison just 11 months before.

“If there were another girl, would you have taken her?” the judge asked.

“I don’t know how to answer that.”

He said he was driving an orange car then. He said Angie was crying, cold and tired. He insinuated that Angie got in his car willingly.

“So I said, ‘If you want to sit down, sit down,’ and she did,” he said.

His public defender, Michael Sato, then had a sidebar with his client – one of several. The 20 or so friends and family members allowed inside the socially-distanced courtroom gallery audibly gasped and a few shook their heads. About 20 people watched the hearing from a gallery set up outside the courtroom with a TV.

Cunningham quickly moved on, asking if Cox assaulted Angie with an object.

“As far as I know, yes,” he said.

Lohmar said it is typical for child predators to try to distance themselves from the more awful aspects of their crimes, or minimize them as a way to perhaps try to live with themselves.

Lohmar told me at least twice when Cox shuffled his way to the witness stand and back to his council table, he glared at him.

"There was nothing weak and feeble in those eyes," he said. "Pure evil."

Cox certainly did that several times Thursday, especially when Cunningham asked him if he left Angie naked, bound, gagged and tied to a tree in the Busch Wildlife Area with duct tape over her eyes and mouth in the sub-freezing temperatures knowing she would die there.

He didn’t answer right away.

His attorney jumped up again.

It was a key element of the deal – Cox had to admit he knew his actions would cause her death in order to plead guilty to first-degree murder.

Lohmar told me in his initial confession, he tried to say he put here there hoping someone would find her. But the evidence – including the fact that the location was so remote and he didn’t give her any way to scream for help – proved otherwise.

Cunningham repeated the question.

“Yes, sir,” Cox said.

Five people gave victim impact statements. First, Angie’s step-father and half-brother Ron Bone Sr., 61, and Ron Bone Jr., 29, spoke. Angie was living with them at the time of her disappearance.

Her step-father was once considered a suspect. Diane Bone died in 2016 from cancer at 52, but her husband told the court she died of a broken heart long before that.

“I believe in an eye for an eye,” he told Cunningham.

His son tearfully told the court how his mother was never the same after his sister’s murder.

“I already lost a sister, and, at 10 years old, I had to keep my mom from harming herself,” he said.

He said he blamed himself for the murder, too. He was a toddler, and his mother was working two jobs as well as taking care of him. She usually met Angie at the school bus, but that day, her son had taken a nap and she had dozed off, too, her sister, Sandra Hill, told me.

“If I had not been such a rambunctious 2-year-old, maybe she’d still be alive,” he said.

During her statement, Hill turned to her nephew and told him he wasn’t a mistake and the family loved him. She also described Angie as an extremely trusting little girl, and said Cox exploited her kindness as a weakness. She talked about how the family didn’t teach Angie about stranger danger.

“We don’t teach our kids to be scared to go out in the world,” she said.

One of Angie’s cousins also spoke, as did Hill and her biological father’s sister, Debbie Skaggs.

Skaggs told the courtroom that her brother chose not attend the hearing, fearing he would attack Cox and not be able to handle the graphic details of his daughter’s final days.

Cunningham then asked Cox if he wanted to make a statement.

“No sir,” he told him.

Cunningham then made a statement of his own before imparting his sentence.

“Every child has a right to grow up,” he said. “You robbed Angie of all of that.”

He continued: “I would say your sadistic actions are every parent’s worst nightmare, but every parent couldn’t imagine a nightmare like this.”

He talked about the “anguish” that’s gone on within Angie’s family and the community for a quarter century.

The hearing concluded with Cunningham drilling Cox on whether he was pleased with his attorney’s representation -- another requirement to prevent any questions down the line on the legitimacy of the sentence.

That’s when Cox had the most to say.

“He spent a tremendous amount of hours with Mr. Lohmar, and, as far as I’m concerned, he’s one of the best attorneys in the country,” he said.

He shuffled back to his seat. Cunningham adjourned the hearing. Reporters dashed out the door to make their 4 p.m. live TV reports with 20 minutes to spare, print deadlines and radio broadcasts.

Some family members lingered until Cox left the room.

And the air came back in.