ST. LOUIS — Judge Stephen Clark wanted to send a message.

So, he gave three former St. Louis aldermen indicted on public corruption charges prison terms just one month shy of the maximum federal guidelines would allow.

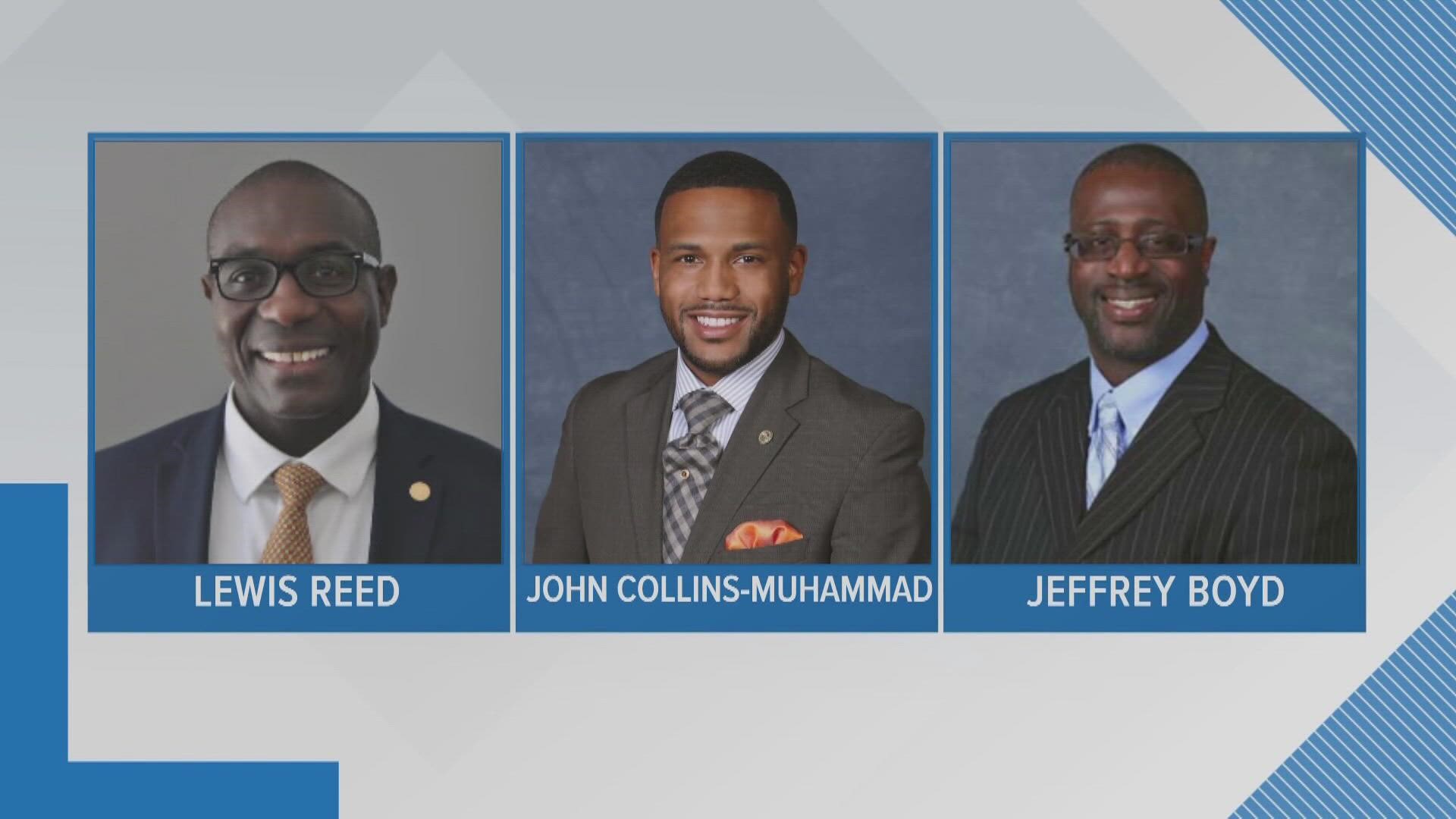

For former Board of Alderman President Lewis Reed, that was 45 months.

For former Alderman Jeffrey Boyd, that was 36 months.

For former Alderman John Collins-Muhammad, that was 45 months.

Clark spent hours painstakingly reading through all of the factors he considered before arriving at his decisions in each case Wednesday.

In all, the sentencings took about four hours.

“I have to think about deterrence,” Clark said before handing down his heavy sentences.

But the deterrent effect Clark so vehemently pursued in the heavy sentences he handed down this week just might be undermined by a law enacted by the very man who put Clark on the bench.

In 2018, then-President Donald Trump signed the First Step Act into law.

The next year, Trump appointed Clark to the bench despite heavy opposition from The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights for his views on the LGBTQ community and abortion.

In each sentence Clark doled out Wednesday, Clark talked about how he read every letter that was sent to him regarding each of the politicians.

Most of them urged leniency.

Others urged him to throw the book at them.

Regardless of the sentences Clark gave, the First Step Act was most certainly on the minds of their defense attorneys.

The federal Bureau of Prisons defines the First Step Act as a “culmination of a bi-partisan effort to improve criminal justice outcomes, as well as to reduce the size of the federal prison population while also creating mechanisms to maintain public safety.”

The act allowed federal inmates to earn up to 54 days of good time credit for every year of their imposed sentence rather than for every year of their sentence served, according to the Bureau of Prisons.

It uses the following example: If an offender is sentenced to 10 years in prison and earns the maximum good time credits each year, the offender will earn 540 days of credit.

Then, there is credit for completing substance abuse and mental health programs behind bars.

Time earned via the First Step Act plus credit for an alcohol abuse program helped former St. Louis County Executive Steve Stenger get out of federal prison in 27 months, not the 46 months he was originally sentenced to serve for his public corruption scandal in April 2019.

Nonetheless, knowing that each man would be sent to prison at all weighed heavily on them and those who came to support them at the hearings.

As Collins-Muhammad left the courthouse, his eyes and cheeks were swollen from tears he tried to wipe away.

Boyd’s family shouted, “no comment,” to reporters who asked, “What do you have to say to the taxpayers?” as they walked by.

Reed’s family engaged in some fireworks following his hearing, which included yelling profanities at a man who claimed to be a taxpayer victimized by Reed’s greed.

The man tore up a resolution that Reed had signed honoring a poetry program for children, saying it meant nothing because Reed’s signature was on it.

After that bit of unexpected theatrics, which also caught Clark off guard, the man sat just 10 feet away from Reed’s wife. She wept through much of the hearing.

She walked out of the courtroom as soon as she heard Clark say “45 months.”

Not long after Clark swung his gavel to end the hearing, one of Reed’s supporters approached the alleged taxpaying victim and shouted profanity at him. U.S. Marshals surrounded her and escorted her out of the courtroom. They then escorted the man to the elevators as about two dozen Reed supporters continued shouting at him.

When Reed walked out of the courtroom, they applauded him.

He, his wife and his children tearfully embraced.

Then, Assistant U.S. Attorney Hal Goldsmith walked out, and they launched profanities at him.

Reed waived them off.

“Stop, just stop,” he said, as he waved his hands at them.

They listened.

Reed then got into an elevator with his attorney, Scott Rosenblum.

About three years ago, Rosenblum got into one of those same elevators at the federal courthouse with his client at the time: Steve Stenger.

Figuratively speaking, I’m fairly certain Rosenblum was holding a copy of the First Step Act in his back pocket Wednesday, too.