Byers' Beat is a weekly column written by the I-Team's Christine Byers, who has covered public safety in St. Louis for 15 years. It is intended to offer context and analysis to the week's biggest crime stories and public safety issues.

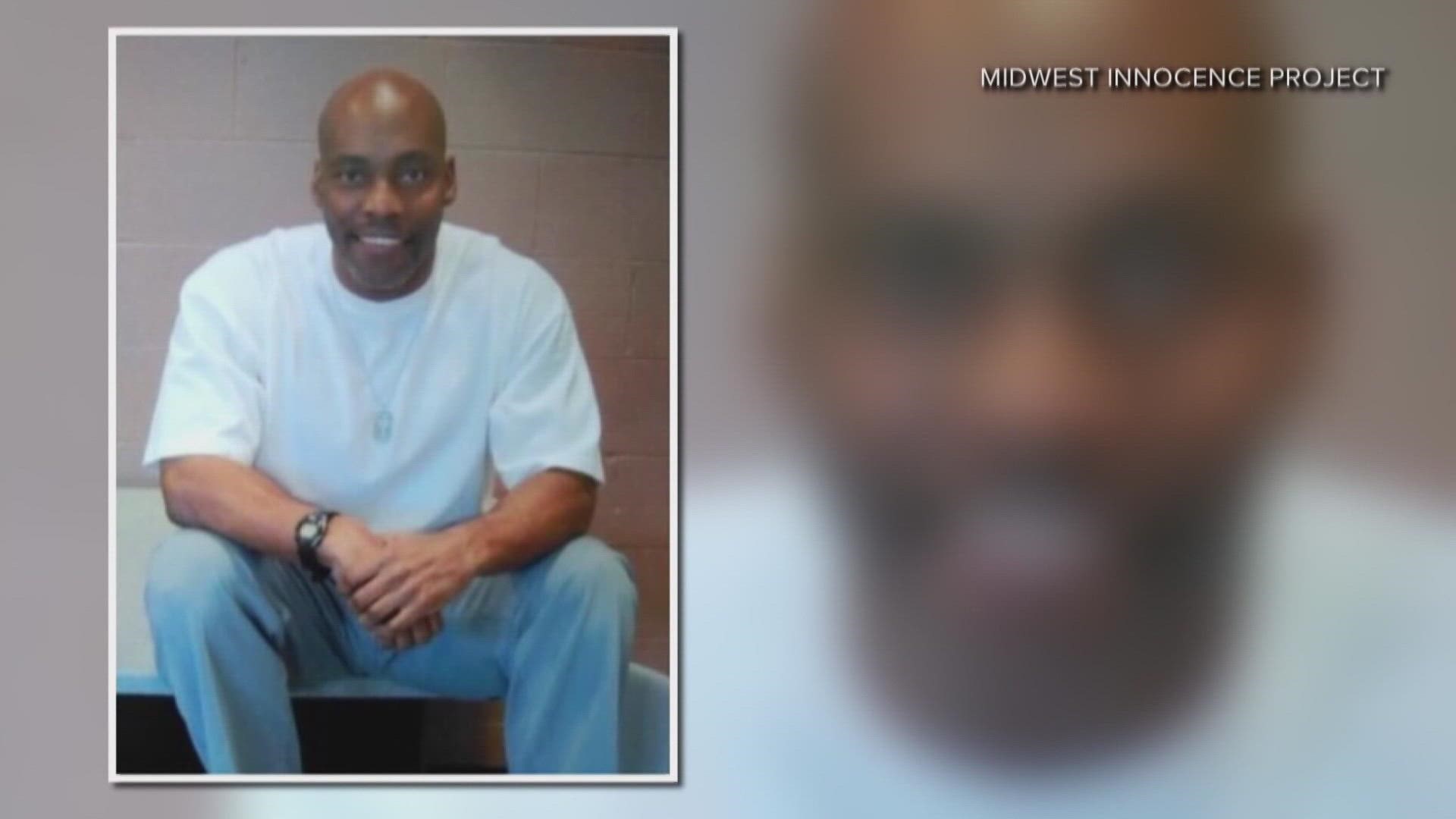

ST. LOUIS — In 1995, it took a St. Louis jury 1 and one-half hours to convict Lamar Johnson for the murder of Marcus Boyd.

Now, Judge David Mason has begun his process of determining whether that verdict should stand, or if Johnson is an innocent man.

This week, the Missouri Attorney General’s Office submitted its final plea to Mason as to why Johnson’s conviction was constitutional and should stand.

St. Louis Circuit Attorney Kim Gardner submitted her final plea in December to the judge, saying Johnson is innocent and shoddy police and prosecutorial work led to his wrongful conviction.

The two sides battled it out during a week-long hearing before Mason in December.

The showdown followed years of arguments from both sides about Johnson’s guilt.

In its 129-page post-hearing brief, the Attorney General’s Office focused on debunking three main reasons why Gardner’s office argued Johnson is innocent.

Here’s a look into them.

Another man has confessed

During the December hearing, a man named James “B.A.” Howard testified and confessed to being the real killer on the stand.

The moment – as did many during the hearing – prompted the judge to ask his own questions.

He wanted to know whether Gardner planned to charge him given his confession.

She told him it was “under review.”

The Attorney General, of course, saw it differently.

“Howard's testimony was so incredible that the Circuit Attorney could not answer whether she would charge Howard with the murder,” according to the briefing. “The only reasonable inference that the Court can draw from the Circuit Attorney’s answer is that the Circuit Attorney does not intend to charge Howard for murdering Boyd.

“The reason is obvious: Howard’s testimony is not credible.”

But why would Howard confess to a murder he didn’t commit?

The Attorney General’s Office explored that, too, and said Howard has a motive to lie on Johnson’s behalf and alleged he is even benefitting from it.

“During cross-examination Howard admitted that he would sign anything — including without reading it — if he thought it would help Johnson,” according to the briefing. “Howard explained that he did not read any of his affidavits before signing them.”

Howard was also 17 at the time of the murder, so he would not be eligible for the death penalty, the state noted.

“Howard is already serving life without parole consecutive to 320 years for other offenses, including murder, and so he is facing fewer potential consequences for his testimony than someone who is not in state custody,” according to the brief. “And on top of all of that, Howard and Johnson are longtime friends and members of the Darkside gang.

"Howard, in other words, provided incredible testimony helpful to his friend because Howard has little to fear from another murder conviction or from a perjury prosecution.”

At the hearing in December, Howard denied getting anything of value in exchange for his testimony.

The Attorney General alleged that was untrue, too.

Howard is represented by John Aisenbrey, who was the treasurer for the Midwest Innocence Project and was on the board of directors for the nonprofit during the time it was litigating Johnson’s case.

“Howard denied knowing this,” according to the state’s briefing. “Given all of this, it is implausible that Howard testified truthfully when he denied having received anything of value in exchange for his testimony.”

The judge asked Howard if anyone told him he could be exposed to additional punishment by testifying.

“Howard testified ‘no,’” according to the state’s briefing. “But Special Circuit Attorney Charles Weiss told the Court that he and Special Circuit Attorney Jonathan Potts had told Howard that he could face additional charges with additional punishment.”

The Attorney General’s Office also accused Howard of getting a few details wrong about the murder that the real killer would know.

Howard told the court his mode of operation was to kill his victims by shooting them in the back of their heads.

Boyd was shot in the back of the neck.

Howard is also considerably shorter than Johnson, who matches the height of the killer the eyewitness described.

The state also suggests Howard’s motive for the murder doesn’t match what others said about the victim.

Howard said he and the other man convicted of acting with Johnson to kill Boyd wanted to kill Boyd to steal his safe. The eyewitness to the murder testified at the hearing that this was “a straight execution,” a “planned murder,” not a robbery. Boyd’s girlfriend testified that Boyd was not known for carrying large sums of cash and that her boyfriend was not “flashy” and didn’t own a safe.

The state ended its skewering of Howard’s testimony by noting how it is undisputed that Phillip Campbell is the second gunman.

Campbell testified that he and Johnson killed Boyd.

“The Court cannot ignore those under-oath statements,” the state wrote.

The witness has recanted

James Greg Elking was there the night two gunmen stormed onto Boyd’s front porch and killed him.

The state summarized the night in question with the following: Elking and Boyd were former coworkers, sitting on Boyd’s porch on the night in question. Elking said he sometimes bought drugs from Boyd and went to his house that night to ask if Boyd would give him a ride to work that following Monday and promised to repay him some money he owed him. Elking said he stayed on the porch while Boyd helped his girlfriend and their baby to the upstairs apartment with groceries.

The friends talked for about 20 to 30 minutes after that on the porch when suddenly two men changed their lives forever.

Gardner’s office focused on how flawed the police identification process was for Elking, who told them despite the gunman wearing a mask that covered his nose and mouth, he had a “slant” to his eyes. One was slightly lower on his face than the other. Elking told police the killer’s eye was “lazy.”

Gardner’s predecessor’s office offered Elking money to relocate after he said he was fearful that Johnson would hunt him down and kill him.

The state alleged Johnson was overheard shouting to another inmate in jail how he should have “killed the white guy,” and also told the same thing to a detective investigating him for an unrelated homicide. Elking is white.

Gardner’s team poked holes in those statements, saying there is no record of an inmate by that name who was in jail with Johnson to have heard him say that, and that the conversation with the detective was not recorded.

The state struck back, saying giving money to witnesses who are fearful of retaliation so they can safely relocate is a common practice, and that money was given to Elking after he had already identified Johnson and prosecutors had what they needed from him.

And, the state alleges, Elking said it “scared the (expletive) out of him” when a letter from Johnson arrived at his new address after the trial.

As the years passed, Johnson and Elking continued to talk about the murder and Elking became convinced he had identified the wrong guy.

In 2003, Elking signed a deposition Johnson asked him to sign, in which he said he never saw either gunman have a "lazy" eye, nor did he tell Detective Joe Nickerson about it.

At the December hearing, however, Elking said he “recognized something familiar … about the eyes in one of the photos,” Nickerson showed him at a diner.

“That familiar thing is the slant in Johnson’s eyes, which Elking has described as lazy,” the state wrote.

The state said in its post-hearing briefing that Elking’s memory of the shooting can’t be trusted.

“Johnson spent years trying to persuade Elking to recant his testimony before the Midwest Innocence Project accepted Johnson’s case in 2008,” the state wrote. “As a result of the repeated contacts between Elking, Johnson, and later with those working on Johnson’s behalf, Elking’s memory of the shooting became tainted.

“Elking now says two automatic pistols were used in the murder, even though the physical evidence directly contradicts that. When Elking was interviewed by the police, he told them that one suspect had a revolver.”

Johnson had an alibi

Gardner’s office contends Johnson was with his girlfriend, Erica Barrow, at her apartment when the murder happened.

The state argued in its briefing that Barrow was impeached several times while on the stand in December, after there were several differences between her testimony during the December hearing, her trial testimony and her affidavits.

“Johnson’s alibi is no more reliable today than it was nearly 30 years ago when the jury rejected it,” according to the state’s briefing.

Barrow admitted that she could not remember what time she and Johnson arrived at the apartment that night, what time Johnson left, what time Johnson returned, or exactly how long Johnson was gone, according to the state.

The Circuit Attorney’s Office never entered any evidence detailing how long it would take to drive between Johnson’s proffered alibi and the crime scene, “despite having a chance to do so,” according to the state.

“The Circuit Attorney and Johnson have had years to investigate Johnson’s alibi, and even with additional time, private counsel, and the power of the State, no one has been able to present additional corroborative evidence to support the alibi,” according to the state’s briefing. “That leaves this Court with only one possible conclusion: the alibi is not credible.”

What’s next

Judge Mason now has three options:

- Overturn the conviction and find Johnson “actually innocent.” That’s a legal term, meaning all of the new evidence proves Johnson is not the killer and should be released.

- Overturn the conviction on a constitutional error. In this scenario, Mason could side with any number of constitutional challenges Gardner’s office made about how the lineup was conducted or beyond. This would reverse his conviction on an error. That would not mean he found Johnson to be innocent, rather wrongfully convicted on a constitutional violation or violations.

- Uphold the jury’s verdict.

There is no time limit on how long Mason has to decide whether Johnson’s conviction should stand or be reversed.

This column gives you a look into all of the hundreds of pages of final arguments he is now mulling to ensure justice for Markus Boyd and the man a jury took less than two hours to convict of killing him.