Byers' Beat is a weekly column written by the I-Team's Christine Byers, who has covered public safety in St. Louis for 15 years. It is intended to offer context and analysis to the week's biggest crime stories and public safety issues.

ST. LOUIS – It’s hardly been just another week in St. Louis.

Indictments involving high-level public officials have cast an even darker cloud over the governments that run the city and county – which arguably drive how everyone who lives in this region is perceived at the national level.

That’s because most people who live around here don’t say they’re from St. Charles, St. Clair County or Arnold. (Nothing personal to those residents, just making a point).

We say we’re from St. Louis. And so as St. Louis goes, so goes the rest of the region.

The urban core and its immediate suburbs in St. Louis County make up most of the population – so what happens in these areas drives businesses to stay or go. Expand or downsize. Invest or land somewhere else.

Attract families to move here, or fly over, universities to thrive or dwindle, sports teams and conferences to pump millions into the local economy or starve it.

And this week was not good for St. Louis.

Thousands of people in some of the most blighted areas of the city are now left without representation after their aldermen resigned.

The swift resignations will no doubt serve as a bargaining chip their defense attorneys will use in court to try and negotiate a better sentence or plea deal for them should it come to that.

St. Louis County Executive Steve Stenger’s attorney, Scott Rosenblum, told the judge in that case that his client immediately accepted responsibility for his actions by resigning on the day of his first hearing in federal court on corruption charges.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Hal Goldsmith countered by saying Stenger did the people he served no favors by resigning because his removal from office was inevitable. If he didn’t step down, Goldsmith noted, the council was going to impeach him anyway.

Hard to know whether Stenger's prompt resignation mattered to the judge.

He still went to prison.

Arguably, Board of Alderman President Lewis Reed could have remained in office. He had enough allies on the board to ensure any efforts to remove him from office wouldn’t be successful.

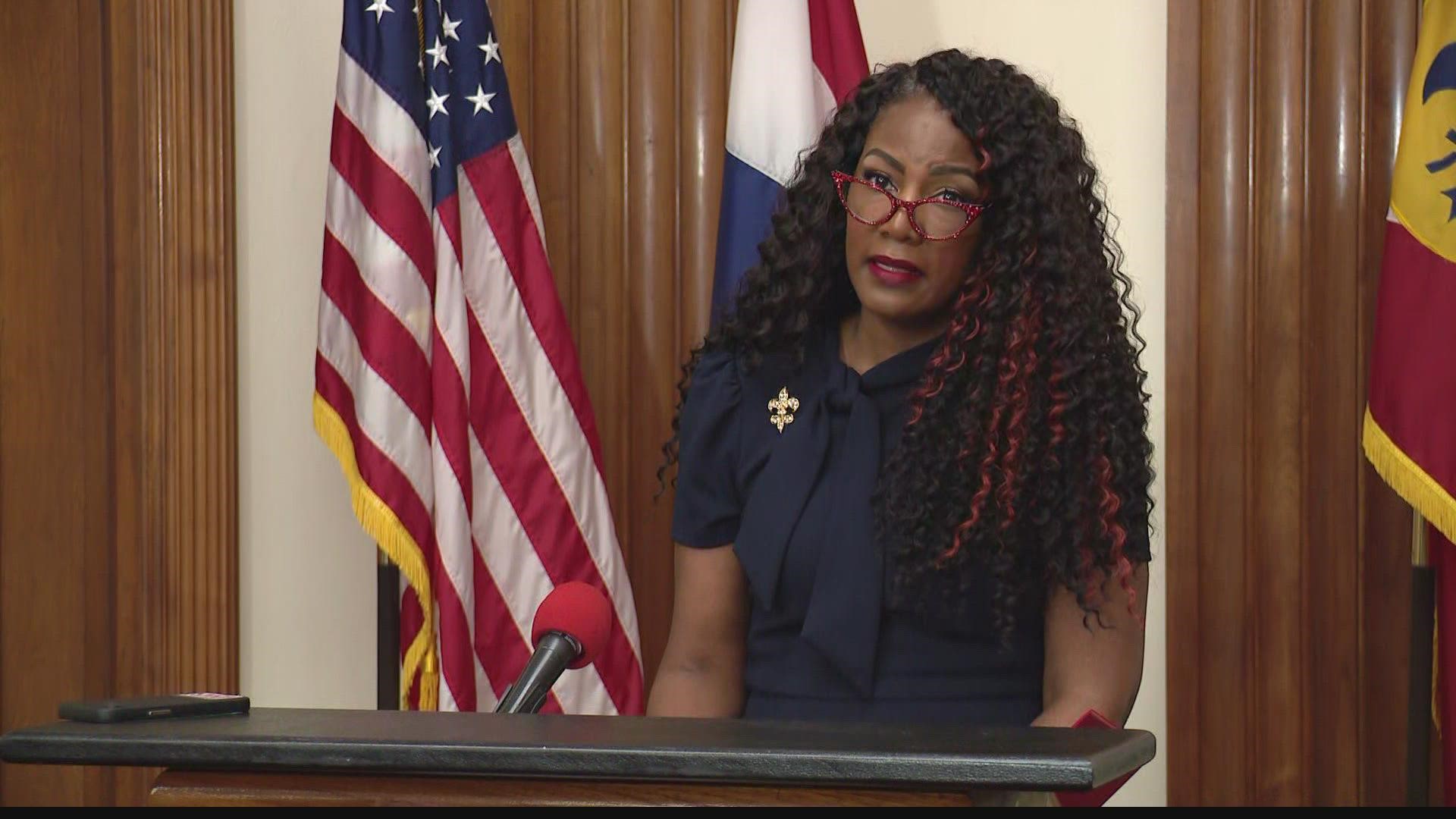

RELATED: 'This is a stain on our city': Mayor Jones addresses bribery charges and resignations of aldermen

He didn't take the chance.

The allegations against all of the men are damning – and complex.

I’ve taken a moment to break down the indictments that prompted Reed and two other St. Louis aldermen to resign, as well as left a top hand-picked aide to St. Louis County Executive Sam Page out of a job.

They all came together like any classic case of public corruption does – one of the players got jammed up for something unrelated.

And, to save themselves, they flipped on as many other people as possible.

In this case, a local businessman who got in trouble with the FBI for selling cigarettes illegally agreed to become an FBI informant and wear a wire while he paid off as many politicians and officials as he could for more than two years.

In exchange, that man – referred to as John Doe and John Smith in the indictments – will be getting a better deal for himself for his own misdeeds.

Here’s what federal prosecutors say he brought them:

The following is a summary of allegations against the men – they have not been convicted of any crimes.

John Collins-Muhammed

Alleged benefits: $16,000 in cash bribes, a $3,000 campaign contribution, a 2016 Volkswagon CC sedan, cellphone

Potential sentence: 35 years

Ward affected: 21

Population: 8,471

Neighborhoods: Kingsway East, Greater Ville, O'Fallon, Penrose and College Hill.

Allegations: Collins-Muhammed is accused of accepting bribes in exchange for supporting tax abatement for a proposed gas station/convenience store his own residents opposed. It began in January 2020 when Collins-Muhammed gave the informant an Aldermanic Letter of Support for a 10-year tax abatement for the property.

The indictment alleges Collins-Muhammed not only lied to his constituents by saying he opposed the project to appease them, but also lied to the informant by telling him another public official needed more money for bribes. He’s accused of then spending that cash on a Trailblazer for himself.

Collins-Muhammed also is accused of introducing the informant to several other public officials, who the informant then bribed or tried to bribe for support on other businesses.

That’s how former Alderman Jeffrey Boyd and Board of Alderman President Lewis Reed allegedly got caught up in the same mix.

Collins-Muhammed also tried to steer a $10,000 cash bribe to an unnamed public official, who then told the informant to give it to him in two $5,000 checks.

But that public official never cashed the checks.

Lewis Reed

Alleged benefits: $15,000 in cash bribes, $3,500 campaign contribution

Potential sentence: 15 years

Accusations: Federal authorities say Collins-Muhammed introduced their informant to Reed, who then helped him get Minority Business Enterprise status for a trucking and hauling company in exchange for bribes.

He’s also accused of promising to give the informant future city construction projects.

Jeffrey Boyd

Alleged benefits: $9,500 cash, about $2,344 in car repairs

Potential sentence: 55 years

Ward affected: 22

Population: 8,520

Neighborhoods: Hamilton Heights, Mark Twain I-70 Industrial, Wells Goodfellow

Accusations: Federal authorities accuse Boyd of helping their informant buy a commercial property along Geraldine Avenue that was owned by the city’s Land Reutilization Authority as well as get tax abatement for the site. He’s also accused of filling out the application for the informant and lying about how much the project would cost and how long it would take to build in order to get better tax credits.

Tony Weaver

Alleged benefits: $300 to $400

Potential maximum sentence: 80 years

Accusations: Weaver is accused of meeting with the same business owner that had bribed city officials while acting as an FBI informant and helping him file applications for four $15,000 COVID-19 Small Business Relief fund grants. According to the indictment, Weaver told the informant they would split the proceeds of the grants, even though the businesses did not close, lay off employees or get behind on bills due to the pandemic. None of the fraudulent applications for grants were awarded, so Weaver never got the money. But he did tell the informant another business owner gave him between $300 to $400 for helping him file an application. The maximum sentence for filing each of the four fraudulent grant applications is 20 years.