Byers' Beat is a weekly column written by the I-Team's Christine Byers, who has covered public safety in St. Louis for 15 years. It is intended to offer context and analysis to the week's biggest crime stories and public safety issues.

ST. LOUIS COUNTY — St. Louis County has its first-ever Black police chief.

It comes off the heels of the department having its first-ever female police chief.

Progressive, right?

But below the surface are multiple discrimination lawsuits – one of which was only avoided by a settlement agreement with the first woman to ever serve as the department’s top cop.

Here’s a little background for those who have not followed the musical chairs among the top brass of the region’s second-largest department.

The St. Louis Board of Police Commissioners, which includes five civilians appointed by the county executive, oversees the police department and hires and fires the chief.

In May 2020, the board chose Mary Barton to replace outgoing Chief Jon Belmar.

The announcement shocked insiders who predicted Lt. Col. Troy Doyle would be Belmar’s successor, given how County Executive Sam Page had arranged private meetings with Doyle and police board members ahead of the vote, along with Doyle’s qualifications. Doyle is also Black.

Instead, after the department’s traditional selection process happened, involving interviews with applicants before the board, Barton came out as the victor.

Months later, Doyle filed a lawsuit accusing Page of orchestrating Barton’s promotion to chief because his political donors did not want a Black man as chief.

He released a recording he secretly made of Page telling him, “The board will do what I tell it to do.”

Barton went on to serve as chief for about 18 months – a tenure that included tension with rank-and-file organizations.

Eventually, she filed an Equal Employment Opportunity Commission complaint against the board, alleging discrimination of her own – which ultimately ended in a settlement that included her resignation in July 2021.

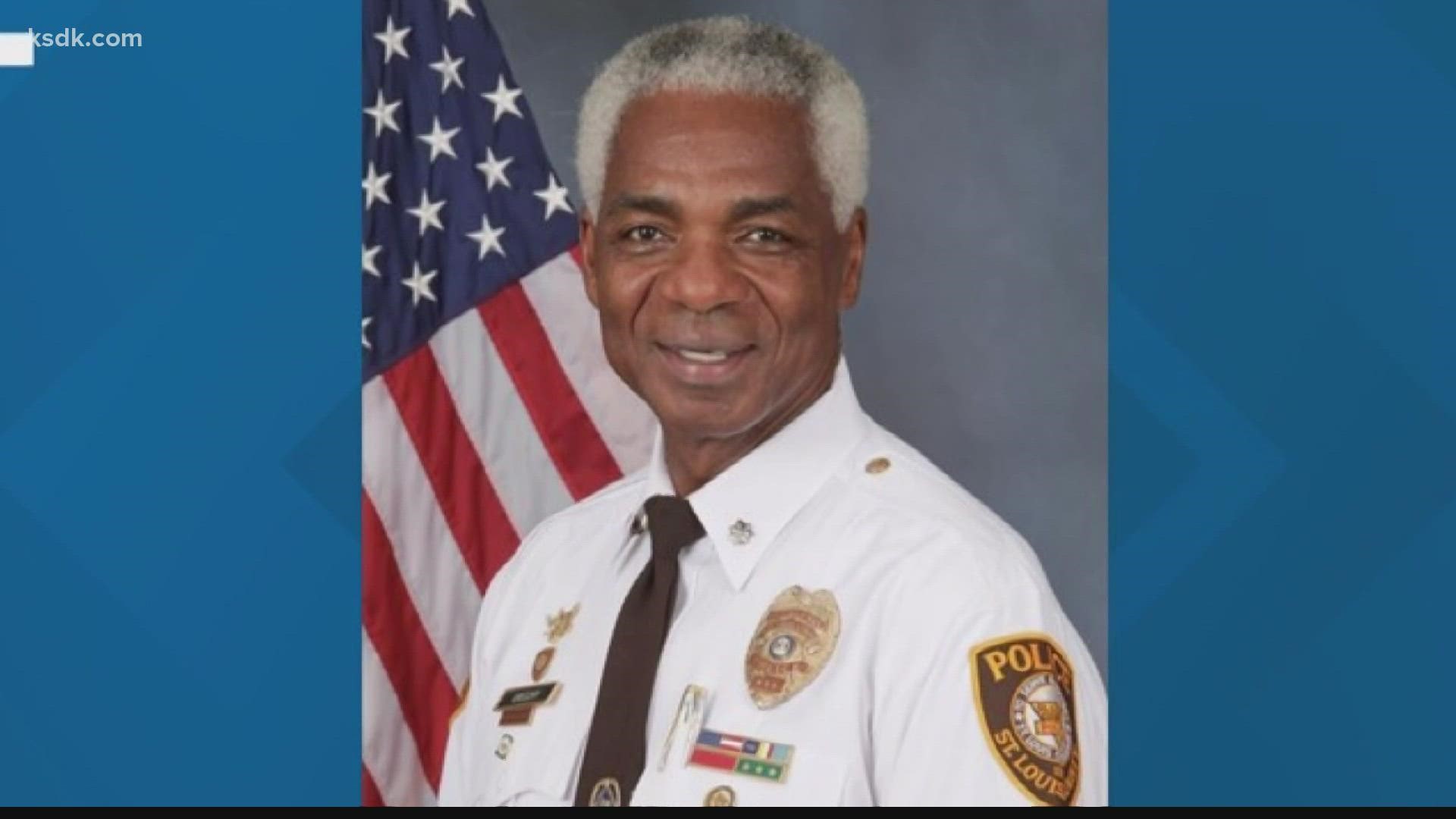

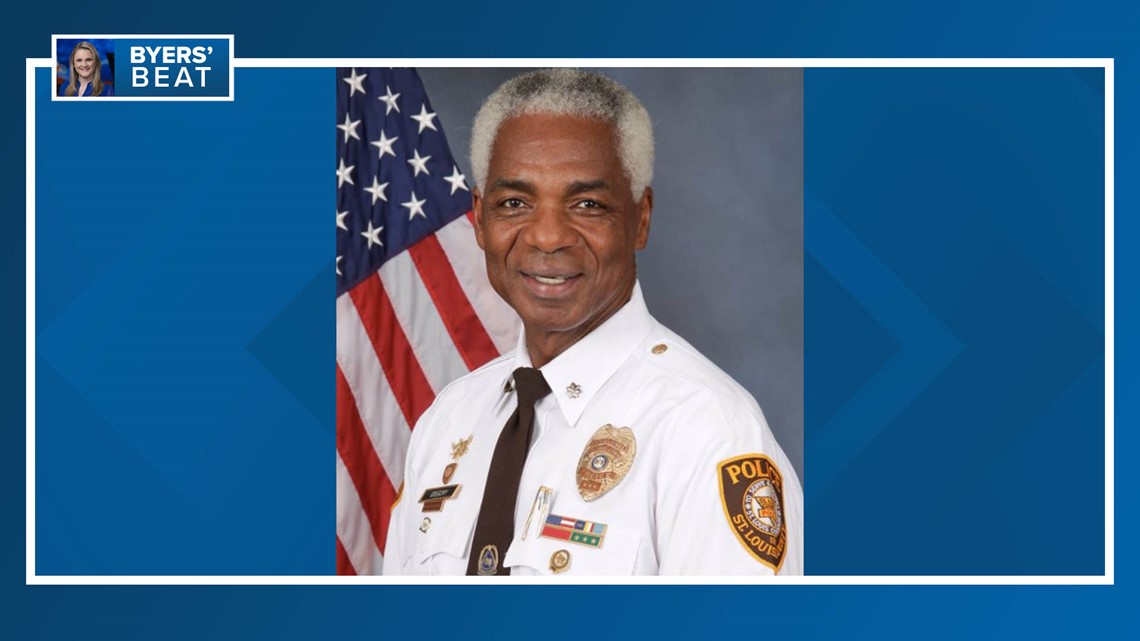

Kenneth Gregory, who is Black, took over as the acting chief and the board announced it would begin a search for a permanent hire.

Gregory did not apply to be chief when Barton was selected and initially told reporters he wasn’t sure whether he would apply this time around.

He’s 69 years old and has 41 years under his belt – having worked in just about every division of the department. There is no question he's qualified for the role.

Then, this week, the board bypassed the application process and anointed him chief. It selected Lt. Col. Brian Ludwig as his second-in-command. Ludwig is white.

The moves did not go unnoticed by Doyle, whose discrimination lawsuit is still pending.

He sent me a statement, which read: “I was looking forward to the opportunity to compete for the chief position, however as a member of Chief Gregory’s executive leadership team, I will continue to support his efforts to move the department forward.”

Doyle’s attorney, Jerome Dobson, was a little more critical.

He said Ludwig’s appointment as deputy chief was another slap in Doyle’s face, as Doyle is the more qualified of the two for that position.

“It's clear the St. Louis County Police Department has a large number of serious racial issues and problems recruiting and retaining African American officers, disparities in discipline and promotions,” he said. “There are problems throughout the entire department.

“It’s well known. The question is whether Chief Gregory is the right person for the job to deal with these serious racial issues. The board said it was satisfied with Gregory’s performance. Thus far, we’re not aware of any efforts he’s made to address these racial issues. If he doesn’t do it when he’s auditioning for the permanent job, the question is, will he do it now that he has the permanent job?”

And now that the department has appointed a Black police chief, does that make the racial discrimination lawsuit Doyle has filed moot?

Not so, Dobson said.

In fact, Dobson said the board’s departure from standard operating procedures of chief selection in the past gives their lawsuit a stronger case for retaliation.

“This is the first time that St. Louis County has filled the chief position without some type of open process,” he said. “They typically make the announcement, list the qualifications, review the candidates, take the top ones, interview them and make a decision. They did none of that this time. The question is, ‘Why?'”

It’s not easy to ask the police board members directly about their reasoning.

All of their meetings for almost two years now have been virtual-only due to COVID-19 precautions – even though the St. Louis County Council had in-person meetings during times of fewer infections.

The police department issued a statement on their behalf before, but has not responded to my question about whether the board will explain why they departed from the normal selection process in this case.

Dobson has his own theory as to why.

He said to remember the county executive’s own words: “The board will do what I tell it to do.”

Appointing Gregory without a long drawn-out process provides political cover for Page, who is up for election this year and doesn’t need a police chief selection hanging over his campaign.

It also flies in the face of Doyle’s accusation that Page would not select a Black man for the job because of racist political donors.

Voters will have to decide whether this is about being progressive, or appearing to be.

"It doesn't change what was done to Doyle," Dobson said.