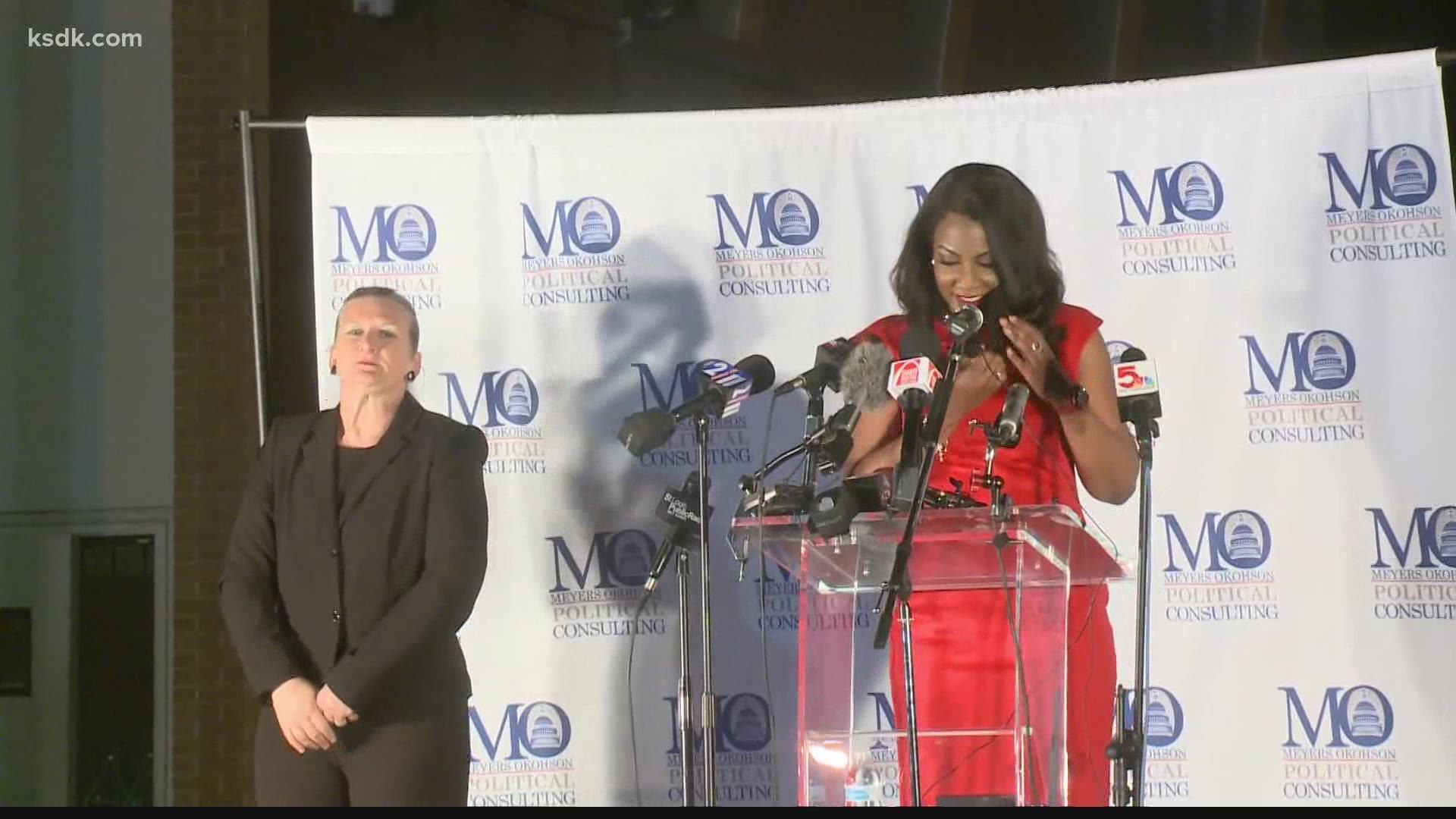

ST. LOUIS — Within hours of winning the St. Louis Mayoral election, Tishaura Jones offered her opinion on why she believes crime is at record highs in the city.

“One of the reasons why we have so much crime is that our children and our young people have no hope,” she said.

She outlined a plan on her campaign website on how she thinks she can turn that around.

Ideas such as:

- a focused deterrence policing strategy

- “sobering centers”

- no-questions-asked drug drop-off sites at police and fire stations

- closing The Workhouse

- ending cash bail

- continuing a program that pairs social workers with cops

- mandating mental health evaluations for police officers

But will it work?

The I-Team took the question to the experts at the University of Missouri-St. Louis and St. Louis University.

Focused Deterrence

All of the criminology professors lauded Jones’ focused deterrence policing approach.

It’s a program that offers social service programs to the most at-risk offenders depending on their needs, such as drug rehabilitation, job training or educational opportunities. But it’s also mandatory.

Refusal to participate means the city will bring every legal strategy it can against that person should they re-offend.

Boston’s Ceasefire program and St. Louis’ own Project Safe Neighborhoods strategy in the mid-2000s are examples of focused deterrence programs, said Joseph Shafer, St. Louis University’s Associate Dean of Research for the College of Public Health and Social Justice.

“The homicide rate went down quite dramatically for a number of years in St. Louis and when that program sort of became less of a focus, we’ve seen homicides go back up,” he said. “It's a great strategy to reduce the problem, but it doesn't make the problem go away.

“And so you need to have a parallel effort looking at issues of building community trust, building confidence between the police and the public, addressing systematic and underlying problems that lead to high rates of violent crime, so focused deterrence sort of helps ameliorate the problem, it addresses the symptom, but not the underlying cause.”

One of the issues Schafer believes hinders focused deterrence programs is the cyclical nature of the offenders it targets.

“These types of strategies focus resources on the highest offenders and those at the highest risk,” he said. “And those offenders are often role switching in various times in their lives, between being high risk of victimizing and high risk of being victims themselves.

“So, doing things that will try to disrupt people's tendency to want to carry firearms, use firearms or place themselves in situations where they may be at risk of firearm violence can be an effective tool and we've seen that in a lot of communities across the country, it doesn't fix the problem if communities are not consistently intentional about it.”

Shafer’s colleague, Professor Kenya Brumfield-Young, added focused deterrence programs have “shown great strength.”

“Over time, there’s been some diminished progress, after about the first two to three years,” she said.

She noted Jones’ plan also includes a focus on de-incarceration.

“With focused deterrence, for those who don't participate there's harsher penalties, often federal penalties and there is an understanding that we can’t incarcerate our way to a solution to these problems,” she said. “So it does look at other alternatives, other than longer harsher incarcerations.”

The University of Missouri-St. Louis’s Professor Lee Slocum added the strategy can have an “immediate impact on crime.”

“That is something the city sort of desperately needs,” she said. “And, in addition to just having the law enforcement focus, it can also connect some social services and community support to the people who are involved in violence, so there is that helping aspect of the potential to offer services to people so that they can turn their lives around.”

Social workers with cops

Mayor Lyda Krewson began a program partnering social workers with cops, that is much like New Haven’s Cops ’N Clinicians program. In St. Louis, it’s been known as the Mobile Crisis Prevention Team.

Social workers and community advocates essentially partner with police officers on patrol, responding to calls with them and following up on others to offer crime victims access to social services directly.

“There’s a lot of national conversation about alternative call response and integration of social workers into police operations and alternative responses, but I don’t think we really know yet how best to do that,” Shafer said. “There really needs to be careful analysis and evaluation there to make sure that those things are ultimately being used in the most effective and productive way possible.”

Mental health for first responders

Shafer noted Jones plan to require mental health evaluations for all police officers, saying mental health should be a priority for all public safety workers.

“Public safety personnel across the city are exposed to exceedingly high levels of trauma and officers are not particularly enamored with the assistance that the city provides them for their mental health and well-being,” he said. “I think that there’s a real need for the city to look at how it's meeting the well-being needs of employees, because employees who aren't having those needs met are going to have decreased performance and may be more likely to separate from the department.

“Obviously we see that happening in a very understaffed police department and understaffed 911 call center, and issues with the staffing in other parts of the city’s public safety apparatus, so I think it's great that there's hopefully some attention that could be paid to the needs of employees as well in this situation.”

Slocum said staffing the 911 call center should be a priority.

“Focusing on fully staffing 911 and retraining dispatchers is critical for having an immediate impact, since we know people have been put on hold, and dispatchers really are the gateway to service provisions for citizens,” she said.

Substance abuse programs

Brumfield-Young likes Jones’ attention to substance abuse programs, but cautioned resources are scarce.

“Right now, there’s a lot of waiting lists for these programs, so access to these programs is very limited,” she said.

Slocum added Jones’ proposal could push more people toward rehab, and the resources to handle that influx need to be in place.

“Allowing people to turn in drugs at fire stations or police stations without being arrested, that’s been shown to facilitate getting people into treatment,” she said. “But as Professor Brumfield-Young noted, there needs to be a lot of investment in the service provision in order to be able to serve all the people who really need it.”

Good-bye to cash bail and The Workhouse

Jones wants to end cash bail to stop people from being held in jail just because they are too poor to post their cash-only bail.

She also wants to close one of the city’s jails known as The Workhouse.

“Jones has a strong focus on decarceration and decriminalization of minor offenses and advocating for the end of cash bail, which will help keep people out of jail as they’re awaiting trial,” Slocum said. “And she has a plan for using those resources that are saved for treatment services.”

All of the professors the I-Team spoke to agreed Jones’ plan won’t come cheap.

“It’s going to be expensive,” Brumfield-Young said. “But the people of the city are worth the investment.”