ST. LOUIS — Editor’s note: This is the second in a three-part series about Concordance Academy of Leadership, a nonprofit aimed at reducing recidivism. The next installment in the series will highlight the story of a current participant. You can read the first part here.

Derrick Mitchell was nearing the end of a 10-year prison sentence when a member of the Concordance Academy of Leadership approached him with an opportunity:

Participate in an 18-month program and your chances of ending up back in prison could be reduced by as much as 44%.

“I was just going through the motions, just trying to survive like every day within there,” he recalled. “And then I was approached with this opportunity and it was like the best day that ever happened to me, the best thing that ever happened to me.”

Mitchell, 39, is one of about 700 people who have participated in the nonprofit’s recidivism prevention program since it opened six years ago in St. Louis County. It's run by retired Wells Fargo Advisors CEO Danny Ludeman, who crafted the program so it could be replicated in any city in the country.

A $50 million fundraising campaign is underway to open branches of the nonprofit in 11 more cities across the country, and he recently got state funding in Missouri.

The program’s success is attracting interest from experts like John Roman — a senior fellow in the Economics, Justice and Society Group at the National Opinion Research Center, or NORC as it’s often called. It’s one of the largest independent social research organizations in the country and it’s based at the University of Chicago.

“Concordance participants do substantially and significantly better than people who are returned to society under a business-as-usual sort of setup, where they just come back and they get some help, but they don’t get the intensive wraparound support that Concordance offers,” Roman said.

Concordance paid NORC to study their effectiveness. Roman compared Concordance participants against those who did not receive services who were released between May 1, 2018 through Aug. 31, 2019 to St. Louis, St. Louis County and St. Charles County.

At six months, instead of having 8% or 9% already back in prison, only 4% had returned to prison in the Concordance group, Roman said.

“That’s substantial reductions in a population that is really hard to serve,” he said. “It's really hard to get people off this trajectory of offending because, for the most part, people don't go to prison the first time they commit a crime.

“They commit lots of crimes before they’re caught. Lots of times they cycle in and out of jail, in and out of court rooms and so by the time they get a sentence that makes them eligible for Concordance, they have a long history of offending and it’s really hard to break that cycle.

“So having 50% or more reductions in new events that cause them to go back is really a substantial, substantial achievement and they're very few examples of programs around the country that have been as successful as Concordance.”

For Mitchell, an argument with his former girlfriend landed him a conviction for burglary, assault, armed criminal action and resisting arrest in St. Charles County. He said she found out he got another woman pregnant, changed the locks on the home they shared, so he broke in and they fought.

“A five-minute thought can cost you 10 years of your life,” he said.

His mother and grandmother also died, so he felt like he didn’t have much family support.

“It was very, really bleak,” he said. “I didn't know where I was going, what I was going to do. You just feel like you don't have a chance, a shot in this world once you become a felon.”

Six months before his release, Mitchell worked with a Concordance staff member to map out a plan for his first 12 months of freedom.

Concordance partners with the Bryan Cave law firm, so participants can get legal help and address any outstanding warrants upon their release – and avoid getting re-arrested right away.

The nonprofit also works with federal healthcare providers to get doctor’s appointments for participants as soon as they are released to address any medical issues that may stand in the way of reintegrating into society.

“They help you begin your process of everyday life,” Mitchell said. “It’s like, ‘Let me show you this is normal life, it’s not over for you, you still have a chance at every goal that you have set forth for yourself in life. You still can achieve these things and be these things.”

And Concordance provides its participants intensive mental health services for weeks before any employment can begin and permanent housing is addressed.

Executive Director Danny Ludeman said many people believe finding employment and housing for inmates upon their release are all anyone needs coming out of prison.

But he calls them the two biggest myths when it comes to rehabilitation.

If a person is still coping with a mental health or substance abuse issue, they won’t keep a job and they’ll likely get evicted, he said.

“If you don’t take care of (mental health), then none of this other stuff really matters,” he said.

On average, Concordance participants have four children.

Mitchell has two.

And they have families eager for them to start earning an income as soon as possible after struggling while they’ve been in prison for so long, Ludeman said.

Mitchell agrees.

“Everybody want to jump, they want to go from zero to 100 without taking the much needed steps in between,” Mitchell said. “I'm not going to lie to you, when I first got here, I was guilty of it. I was ready to work and provide for my family and help out too, but like it's a process.”

Mitchell said jumping back into the workforce immediately causes burnout.

“They end up quitting a job because they are doing something that they don’t want to do,” he said. “A lot of guys who I know is doing time and get out without a program like this, they back within the system within six months to a year.

“The same addiction is a problem because when you are let loose out on the street with nothing to help change your thought process, they resort back to the same thing that they did to get into prison. They can say all day, ‘Well, I'm out here hustling for my family,’ or whatever. But that's just lip service because there's plenty of other ways to get money.”

Concordance pays participants $320 a week during the counseling portion of their reentry program.

So, in a sense, taking care of themselves is their first job.

Mitchell said the counseling helped him cope with feelings of hopelessness.

“We tend to beat up on ourselves, on the things that we have not accomplished rather than focus on the things that we have accomplished,” he said. “I know what I thought, I thought I'd be working in fast food because this is what you think as a felon, you just think we're going to be in fast food for the rest of your life. And I don't do well with fast food. That's why I say how ideas start. I'd probably try to hustle.”

Concordance partners with local employers that are “felon friendly,” Ludeman said.

So Mitchell has been working at General Motors and Schnucks.

But those are his “now jobs,” Ludeman said, adding that many Concordance participants have gone on to earn between $60,000 and $80,000 annually.

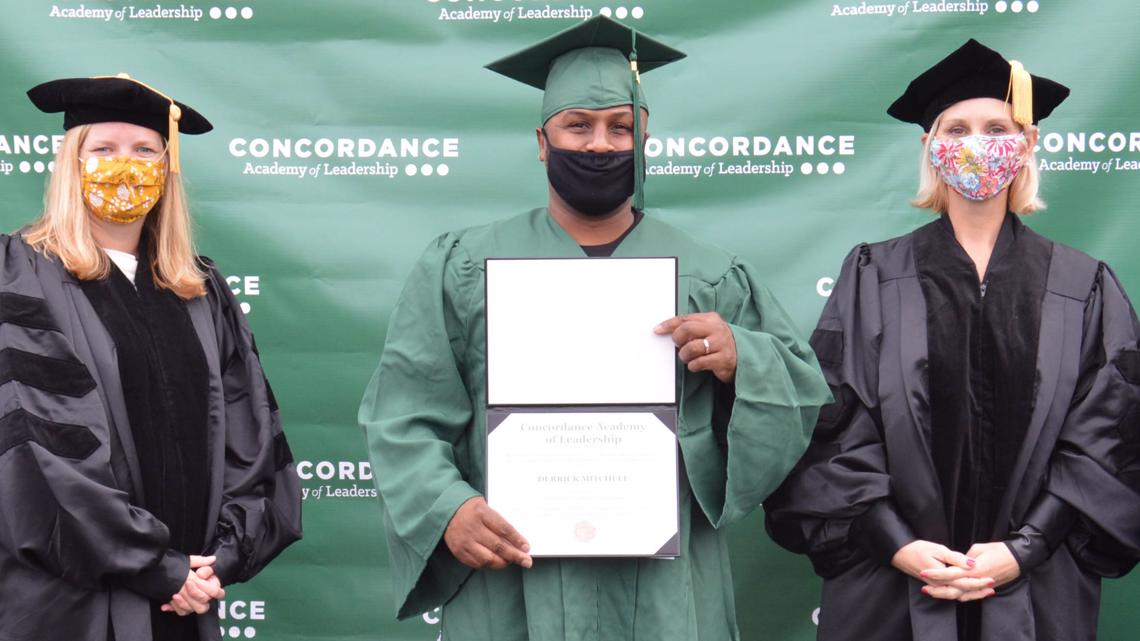

Mitchell graduated from Concordance in October.

He said he wants to start his own tow truck business and has an interest in real estate.

He’s also gotten married, and the couple welcomed their first child together in December.

He’s also reconnected with his 10-year-old daughter.

And is no longer on parole.

“They probably saved my life,” he said.