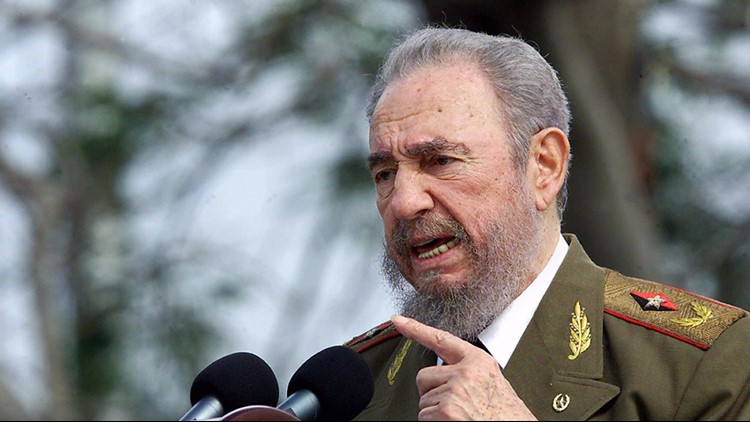

Fidel Castro, the Cuban dictator who helped bring the world to the brink of nuclear war, tormented 10 American presidents and exerted almost total control over the last remaining communist government in the Western Hemisphere, died. He was 90.

His death was reported by the Associated Press, citing state media in Cuba.

For 47 years, Castro maintained his grip over the island nation by forging close bonds with the Soviet Union, Venezuela and China, inspiring a wave of anti-American leaders throughout Latin America along the way.

His undoing began with surgery in 2006 that forced him to cede power to his brother, Raul Castro, and forever changed the image of the man. Gone was the romantic vision of the bearded, cigar-smoking guerilla leading his group of rebels through the mountains of Cuba, replaced by occasional pictures and videos of a frail, old man recovering in bath robes and track suits.

The prolonged physical collapse gave hope to Washington and to more than a million Cuban-Americans who have fled his regime over the decades that a political change would soon follow. But his illness proved to be a blessing to those closest to him, easing the transition to a new leader and ensuring that they remained in power.

And true to his character, it did little to change his view of his own place in history.

“His personality was such that he always saw himself as the man on the horse, the only guy who could possibly do what he has done,” said Dennis Hays, a former chief Cuba analyst at the State Department.

“In his mind, he was the only one who could hold back the tides of time and human nature as he has.”

Castro’s rise to international prominence was a meteoric one. In the span of seven years, he went from solitary confinement in a Cuban prison to dictator of a country that brought the world to the brink of nuclear war.

Once the Cold War ended and the Soviet Union collapsed, Cuba’s status as a security threat to the United States diminished greatly and Castro was left to hold together a system no longer benefiting from Soviet aid.

While universal health care and education remained the pillars of his revolution, crumbling infrastructure, a stagnant economy and widespread poverty became prevalent in Cuba, forcing the country to rely on outside help — including the United States — to simply feed its people.

Yet his influence on America continued, as waves of Cubans took to the seas in makeshift boats and rafts to flee his grip, a flight that continues today. That group — concentrated mostly in South Florida — has steered U.S. policy toward Cuba and helped preserve the now 48-year-oldDOB:2-7-1962 economic embargo on the island, and has become a deciding factor in local, state and national politics.

His influence over his own country is visible everywhere, from the billboards bearing his image to the crumbling buildings to the pre-embargo American-made cars that are still chugging along.

Ever since Castro officially stepped down on Feb. 19, 2008, and his brother was named president, he watched as Raul Castro made several changes to Cuba, lifting prohibitions set in place by his brother, releasing dozens of political prisoners and taking small steps toward a more capitalist economy. While U.S. officials have dismissed the changes as cosmetic, Phil Peters of the Lexington Institute said Raul Castro’s rush to implement them speaks volumes about the Cuba that Fidel Castro left behind.

“It shows that when he left office, the socialist system was on an unsustainable course,” Peters said. “And it shows that politics and ideological purity always came first for Fidel, even at the expense of an economy that could function and provide for people’s basic needs.”

Fidel Castro Ruz was born into a moderately affluent family, owners of a sugar-cane plantation in Cuba’s eastern Oriente province. His father, Angel Castro, was a self-made immigrant from Spain and his mother, Lina Ruz, had been the family cook.

Castro, one of eight children, went to Catholic elementary school and graduated from Belen, a prep school in Havana run by Jesuit priests.

He excelled in both academics and sports and was voted Belen’s best athlete in 1944. His preferred sport: the thoroughly American game of baseball. He’s said to have dreamed once of becoming a major league player in the USA.

Castro would later seize all the church-run schools in Cuba and be excommunicated by the Roman Catholic Church.

Castro studied at the University of Havana and earned a law degree. He also acquired a taste for politics as a student activist.

“I was acquiring a socialist consciousness I had initiatives, I was active and I struggled,” he recalled in a 1982 interview with Colombian journalist Arturo Alape. “But let’s say that I was an independent struggling person at that time.”

In 1952, Fulgencio Batista staged a military coup that established a military dictatorship and propelled Castro into the role of revolutionary.

On July 26, 1953, Castro, Raul and 150 followers attacked the Moncada Barracks in Santiago de Cuba. The assault failed and many of Castro’s men were killed or captured. Castro was tried and sentenced to 15 years in prison.

On trial, Castro delivered a speech that became known by its final line.

“I know that imprisonment will be harder for me than it has ever been for anyone, filled with cowardly threats and hideous cruelty,” Castro told the court. “But I do not fear prison, as I do not fear the fury of the miserable tyrant who took the lives of 70 of my comrades.

“Condemn me. It does not matter. History will absolve me.”

Castro, freed in a 1955 amnesty, went into exile in Mexico where he recruited and trained guerilla fighters. That’s where he met Ernesto “Che” Guevara, an Argentine Marxist who would become synonymous with Castro’s revolution.

The next year, Castro and more than 80 followers boarded a boat named Granma and landed in eastern Cuba, setting up camp in the Sierra Maestra mountains near his boyhood home. Dubbed the 26th of July Movement, the rebels seized weapons in attacks against Batista’s military and received food and shelter from sympathetic Cubans.

Castro then began a slow march west, gaining in popularity as Batista was facing trouble all around. Even the U.S. government had lost faith in Batista, stopping arms shipments to him in 1958. On Jan. 1, 1959, Batista and his family fled Cuba.

That cleared the way for Castro, who rolled into Havana amidst throngs of supporters. He pledged to end corruption. He promised to improve living conditions. He had widespread support on and off the island, even as his true vision for Cuba remained a mystery.

So unclear was Castro’s plan that he was treated to a hero’s welcome during a much-publicized tour of the U.S., where he rounded up support from liberals and curious fascination from many others.

“It was a triumphal procession,” said Mark Falcoff, a former staff member of the Senate foreign relations committee and author of Cuba the Morning After: Confronting Castro’s Legacy. “He was the most popular figure in the U.S.”

It wasn’t long before the new regime began Cuba’s transformation to communism, aligning itself with the Soviet Union.

The new government nationalized businesses and banks, confiscating more than $1 billion in American-owned property. Thousands of so-called “enemies of the revolution” were executed or imprisoned, and school curriculum was reshaped by Communist doctrine. Free speech was not an option, and the Cuban press was an extension of the government. That prompted many wealthy Cubans to leave the country — the first of several waves of Cubans to flee Castro’s Cuba.

In January of 1961, the United States broke off diplomatic relations with Cuba. Exiles in Miami, supported by the CIA, trained in the Everglades to topple Castro. In April of that year, 1,300 Cuban exiles made a disastrous invasion of Cuba at a southern coastal inlet, the Bay of Pigs.

Many in Miami viewed the humiliating event as a betrayal by President John Kennedy, who failed to send additional forces the Cuban exiles had expected. Ill will toward Kennedy, a Democrat, turned many Cuban-Americans against the political party. To this day, they remain among the most loyal Republican voters.

Andy Gomez, a senior fellow at the University of Miami’s Institute for Cuban and Cuban-American Studies, said the failed invasion gave Castro the ability to claim that he was being targeted.

In fact, U.S. intelligence acknowledged eight failed attempts by the CIA to assassinate Castro between 1960 and 1954. But Gomez said Castro continued using the constant threat of a U.S. invasion as a way to control the Cuban population.

“He continues to talk about ‘There will be an American invasion of Cuba,’” Gomez said. “”That’s very unlikely now.”

The United States and the Soviet Union almost went to war over Cuba in 1962, after a U.S. U-2 spy plane photographed the construction of Soviet missile sites in what became known as the Cuban Missile Crisis. Kennedy ordered a naval blockade of Cuba to force Moscow to remove the missiles. Khrushchev agreed, in return for a U.S. promise not to invade Cuba and to remove U.S. missiles from Turkey.

In 1975, U.S. intelligence acknowledged eight failed attempts by the CIA to assassinate Castro between 1960 and 1965.

In later years, U.S. efforts to dislodge Castro centered on economic and diplomatic measures. Tightened trade and travel restrictions replaced blockades.

Tensions continued as Cuban exiles flooded South Florida at various times over the decades. More than 125,000 refugees flooded the United States in 1980 during the Mariel boatlift. In 1996, two planes flown by Brothers to the Rescue — a group that patrolled the Florida Straits for endangered rafters — were shot down by Cuban fighter jets. Castro claimed the planes violated Cuban air space.

The Elian Gonzalez saga took the political stand-off to an international stage. Eleven Cuban refugees headed for Florida died on Thanksgiving Day, 1999, including Elian’s mother. The 5-year-old survived.

Elian’s relatives in Miami fought to keep him in the U.S., while his father in Cuba, with Castro’s fierce support, demanded his return. After a lengthy legal battle and a middle-of-the-night raid on Elian’s relatives’ house in Miami, the boy was sent home in June, 2000.

While the United States has seen wave after wave of immigrants seeking a better life, the occassional bursts of immigrants from Cuba was unique.

In the early 1960s, more than 14,000 children were sent by their Cuban parents to host families in the United States. In 1980, Castro allowed people to leave the island in the Mariel Boatlift, resulting in more than 100,000 Cubans leving the island.

The most stunning exodus occurred in the early 1990s, when tens of thousands of Cubans took to the high seas to avoid the economic conditions that followed the fall of the Soviet Union. Cubans who learned to get by with little during the hardest economic times used their ingenuity to fashion rafts and boats out to make the dangerous trek across the Florida Straits.