It was a snow covered January night in 2014 when Tim Kirchoff and his crew arrived at a burning house on Nancy Drive in St. Charles. The fire looked like it was mostly out, but it flared up while Kirchoff and three fellow firefighters were in the basement, trapping them.

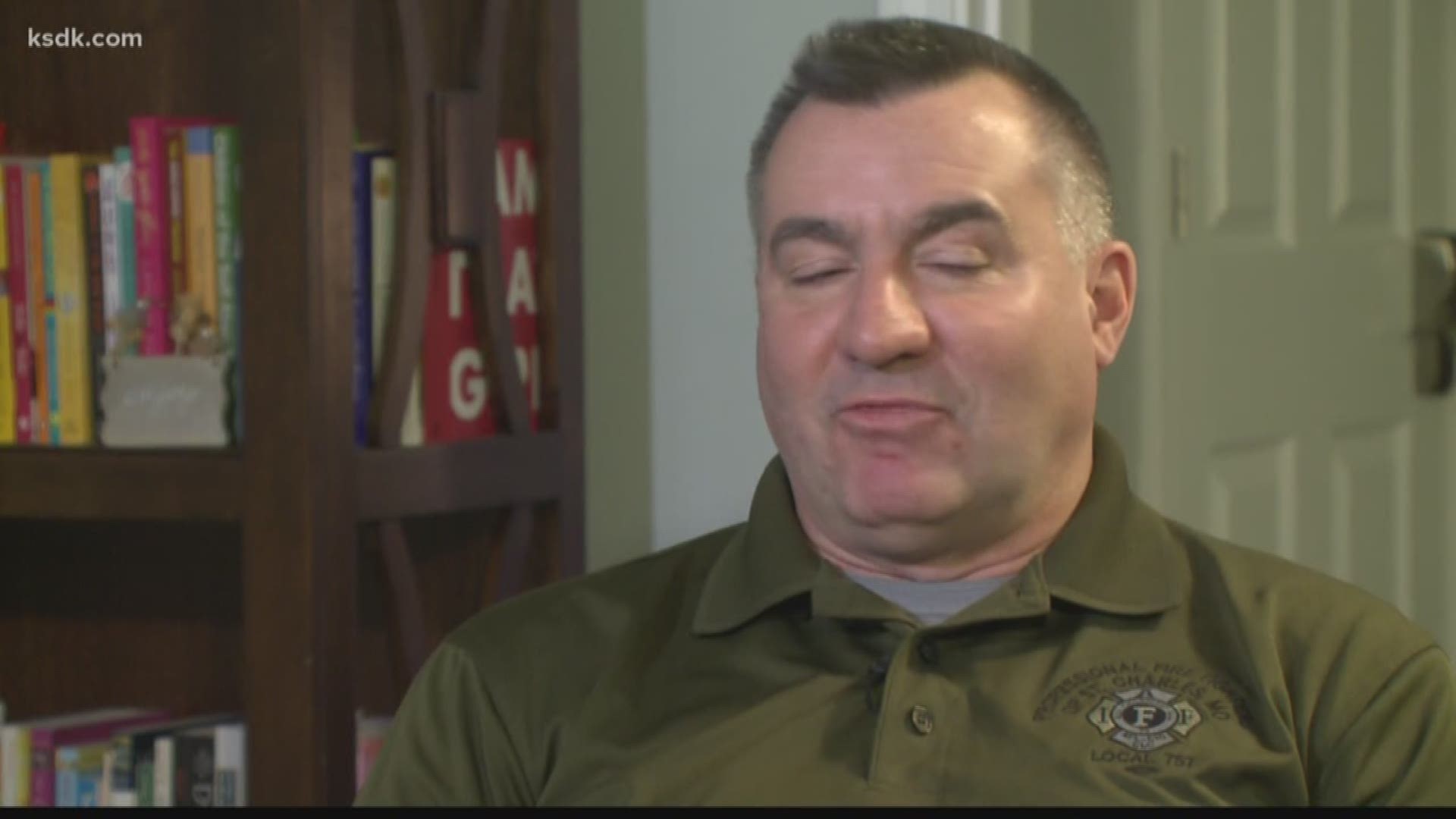

"I got to the point that I curled up on the floor and basically told my wife and kids goodbye," Kirchoff said. He can remember the fire like it was yesterday. "I knew this is the way I was going to die."

Kirchoff's firefighting career started about 15 years earlier when he joined the St. Louis Fire Department.

"As far back as I can remember, it's what I always wanted to do," he said. "I was looking for the action, the excitement and I wanted it to help people."

He did all three first as a paramedic with the department and then as a firefighter. Answering countless calls on one of the busiest trucks in the city, Kirchoff "saw a lot." Most of it, he said, was stuff everyone else would want to forget.

He said he spent eight years with the city department "before deciding I wanted to try and slow down a little bit, maybe extend my life so to speak and try to find a department that the odds of me getting truly hurt or killed would be smaller."

If those odds could ever really be smaller, they still found Kirchoff at his new job with St. Charles the night the fire on Nancy Drive trapped him in that basement.

"Where I was curled up I reached up the wall one last time and there was a window," Kirchoff remembered.

Somehow all four trapped firefighters made it out alive. Several surgeries helped mend Kirchoff's injuries on the outside. But inside, he was only getting worse.

"I was having nightmares. I was reliving it. I could literally feel my skin burning again; I couldn't sleep," said Kirchoff of the months after the fire.

Then came what he called the highlight reel—nightmares not just about that night, but about calls he'd answered throughout his career.

"I was afraid to say a word to anybody," he said of the stress he was suffering. "The fire service, it's always been, you know, 'suck it up buttercup.'"

Like a lot of first responders, doctors now say Kirchoff was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD. One recent study from Ruderman Family Foundation found firefighters and police officers are five times more likely than the rest of the population to suffer PTSD.

"A broken arm, you can put a cast on it and it will heal. PTSD and what firefighters and police officers deal with, this is something they can struggle with the rest of their life," said Anthony Bass with SSM Health Treatment and Recovery who counsels first responders.

Bass said not only are they exposed to the unthinkable, but it can happen several times a day often with little or no time to process the trauma.

"It's a very serious situation," Bass said because of the dangers first responders face. He pointed out that firefighters, for instance, often deal with much more than fires.

And it's taking a deadly toll.

That same study also found more firefighters and police officers die by suicide than in the line of duty.

"Without the support of my family and the treatment that I've received, I probably wouldn't be here right now," said Kirchoff.

Kirchoff said his PTSD made him push his family away and caused the stress to snowball.

He said it "took a few years" before he was able to ask for help. He recalled one day a supervisor said something to him at work. "And I completely lost my temper, and I knew right then I had to say something."

Kirchoff now sees a counselor regularly and relies on his service dog, but he's no longer able to work as a firefighter because of permanent injuries from the fire he survived and his PTSD.

"I just want to encourage any first responder out there, if they even think they have an issue, reach out and talk to someone," Kirchoff said.

"I know I waited way too long."

One place firefighters are getting help in the St. Louis area is the non-profit Responder Rescue.

Pat Byrne with the organization said it started out with the mission of helping first responders and their families with physical injuries or other hardships not covered by other insurance. Now, almost all of the organization's work deals with the PTSD plaguing first responders, she said.