ST. LOUIS — COVID-19 came to Missouri with an unpredictable set of symptoms and a mystery surrounding how it spreads. An unknown number of Missourians who weren’t tested early on have the antibodies today to prove that they were exposed and recovered.

A new study on its way to peer review from scientists at the Centers for Disease Control suggests that there have been thousands more infections than the state identified through testing. The study, preprinted late last week, suggests that more than 150,000 Missourians who were never tested actually had COVID-19 as of late April.

Data from the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services puts the number of people who have received diagnostic polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing to date at 397,318. Those tests have identified more than 21,000 COVID-19 cases.

However, the CDC study estimates that 2.65% of Missourians had already contracted COVID-19 as of April 26. That means almost 24 cases of COVID-19 for every case the state identified through testing.

The CDC analysis comes from samples collected during routine screening of non-COVID-19 patients at commercial clinical laboratories in six areas of the country.

The gap between the number of positive tests and the estimated actual spread of the virus was largest in Missouri out of the six study sites.

During the study period in Missouri, state guidelines restricted testing to people who knew they had been exposed to the virus, had symptoms, or fell in a high-risk category such as living in a nursing home.

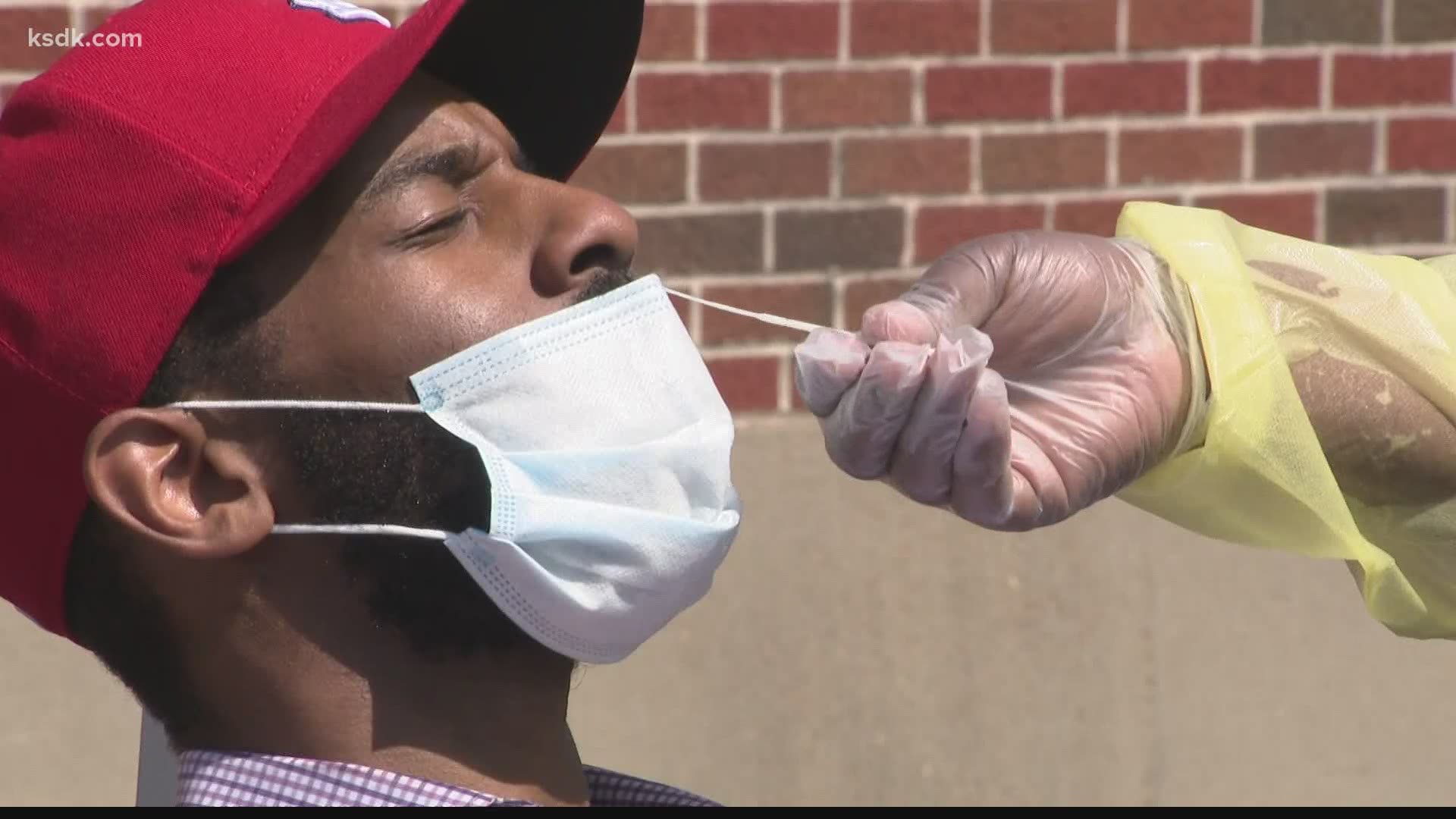

In June, the state opened up testing to anyone regardless of symptoms or known exposure. Care providers such as SSM Health have streamlined their process to get as many tests done as possible.

“We have the process down to literally two minutes, from the time they pull into the tent,” said Chrison Sitton, manager of operations for SSM.

Numbers from the State of Missouri show that PCR testing has increased from an average of 2,331 tests per day for the week ending April 25 to 7,923 tests per day for the last full week of June.

The demand for COVID-19 testing has risen so quickly that provider Quest Diagnostics announced on Monday that new tests for most patients would experience processing delays of 3 to 5 days.

Dr. Alex Garza, head of the St. Louis Metropolitan Pandemic Task Force explained that the people who have COVID-19 antibodies but never got tested might never have known they were sick.

“If you remember when these samples were taken was at the end of April. And at that time, there was very strict criteria for who got tested. So probably there were some people that just weren't allowed to get a test. But there's probably, and this makes sense, a large portion of people that were either asymptomatic or had very mild symptoms and just never bothered to go and get a test,” said Garza.

The CDC study looked at a statistic called seroprevalence, which is the percent of people in a population who have the COVID-19 antibodies in their blood. And although a seroprevalence of 2.65% in Missouri is higher than the state’s testing data shows, it’s still far from what scientists consider to be herd immunity. That’s the level of seroprevalence where enough people have immunity that the virus can’t easily find new people to infect.

“Herd immunity is when you reach about 65% of the population, so 65% of the people are immune to the disease,” said Garza. “So you can see that large gap between where we were in April to where we need to be to have herd immunity.”

The study location with the highest seroprevalence recorded was the New York City metropolitan region. Almost 7% of the population there may already have antibodies for SARS-CoV-2, which is still far from the herd immunity level.

Garza added that waiting on infection levels to rise that high will take too long. “I believe we'll have a vaccine before we reach natural herd immunity,” he said.

The seroprevalence statistic also affects estimates about what percent of people who contract COVID-19 will die of the virus. Analysis of those numbers too have shown that there may be more coronavirus-related deaths than were previously known.

Garza pointed out that excess mortality calculations show that there have been higher rates of death during the pandemic attributed to causes outside of COVID-19. In a study released yesterday in the Journal of the American Medical Association, researchers sought to estimate how many deaths were either caused by COVID-19 and not identified through testing, or were caused indirectly by the virus because of how medical care and the economy changed during the pandemic.

The study identified around 87,000 deaths in the US that rose above expected rates from March 1 through April 25. Only 65% of those deaths were officially connected to COVID-19.

Missouri data included 519 excess deaths in those months. Most were officially COVID-19 related, but 184 of those deaths were not marked as related to coronavirus and might actually have been the result of an undiagnosed case of the virus or might fall under the category of deaths indirectly caused by the pandemic.

An upcoming study from the CDC will use blood donor samples to estimate COVID-19 antibody seroprevalence in 25 cities across the country. According to the public information officer for the City of St. Louis Department of Health, St. Louis will be one of those study locations.