HOUSTON — Secrecy surrounding executions could hinder efforts by a group of medical professionals who are asking the nation's death penalty states for medications used in lethal injections so that they can go to coronavirus patients who are on ventilators, according to a death penalty expert and a doctor who's behind the request.

In a letter sent this month to corrections departments, a group of seven pharmacists, public health experts, and intensive care unit doctors asked states with the death penalty to release any stockpiles they might have of execution drugs to health care facilities.

"Your stockpile could save the lives of hundreds of people; though this may be a small fraction of the total anticipated deaths, it is a central ethical directive that medicine values every life," according to the letter.

But it's unclear what drugs the states may have, as they have tended to release information about execution protocols and drug supplies only through open records requests or lawsuits. Only one state, Wyoming, responded directly to the letter, and it indicated it doesn't have the drugs in question.

"I'm not trying to comment on the rightness or wrongness of capital punishment," said Dr. Joel Zivot, one of the medical professionals who signed the letter. "I'm asking now as a bedside clinician caring for patients, please help me."

For most people, the new coronavirus causes mild or moderate symptoms, such as fever and cough that clear up in two to three weeks. But for some, it can cause severe illness, requiring them to be placed to ventilators to help them breathe.

Many medications used to sedate and immobilize people put on ventilators and to treat their pain are the same drugs that states use to put inmates to death. Demand for such drugs surged 73% in March.

Twenty-five states have the death penalty, while three have moratoriums on capital punishment.

While some states contacted by The Associated Press, including Alabama and Florida, didn't respond to inquiries about the letter, others, including Arkansas, Texas and Utah, limited their comment to mainly saying they don't have the medications in question. Tennessee wouldn't confirm whether it has the drugs and indicated it has no plans to give any medications to a hospital. Oklahoma said it hadn't received any requests for such medications from state hospitals.

States may be hesitant to turn over their drugs because they have had problems securing them as many pharmaceutical companies oppose their use in executions, said Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center.

Since 2011, 13 states have enacted new statutes that conceal information about the execution process, according to the Death Penalty Information Center, which takes no position on capital punishment but has criticized the way states carry out executions.

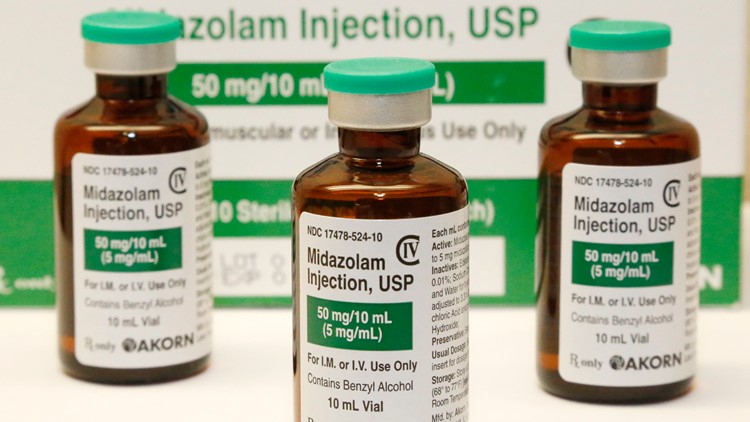

Drugs being requested include the sedative midazolam, the paralytic vecuronium bromide and the opioid fentanyl. They're needed because putting a patient on a ventilator "with no drugs ... would be torture," said Zivot, an associate professor of anesthesiology and surgery at Emory University in Atlanta who has studied medicine's role in capital punishment.

The tense debate over the supply of execution drugs was highlighted in a 2018 lawsuit that several pharmaceutical companies filed against Nevada over accusations that it illegally obtained its inventory.

In a court brief, 15 states, including Florida, Oklahoma and Texas, called the lawsuit part of the "guerrilla warfare being waged by antideath-penalty activists and criminal defense attorneys to stop lawful executions."

The lawsuit was dismissed this month after Nevada agreed to return its supplies to the companies, leaving the state without any drugs to carry out executions.

Pharmaceutical companies have long warned that states' use of these medications for executions could result in shortages, Dunham said.

"Some of the responses over the past several years had been, 'That's chicken little saying the sky is falling,'" Dunham said. "But with COVID-19, the sky has fallen."

___

Associated Press writers Kimberlee Kruesi in Nashville, Tennessee, and Sean Murphy in Oklahoma City contributed to this report.