ST. LOUIS — County and state leaders have responded to an I-Team investigation that found that hundreds of tipsters had their personal information released on social media.

Earlier this month, the personal information of nearly a thousand St. Louisans who reported businesses for not following the county's stay at home order was released on social media.

Many of the 900 tipsters asked for anonymity in their messages. Some were reporting their bosses, some were reporting their neighbors.

Many of the tipsters the I-Team spoke with say they wrote in because they wanted to keep people safe.

After St Louis County's stay-at-home order was put into place in late March, County Executive Sam Page asked the public to report those businesses that weren't complying.

Page said releasing the information through a sunshine request wasn't something his office took lightly.

"We recognize that information as to whether or not it would be a public record would be controversial," said Page in a press conference Monday.

Page claims his office was guided by a higher authority.

"We asked the Attorney General for advice before we set up that system to accept complaints and that's why online it advises individuals that unfortunately this is a public record and we have no control over that," said Page, referencing a disclaimer on the county's website that warns tipsters their information could be subject to release under the state's sunshine law.

On Friday, Page's office told us the attorney general's office advised him the emails could be released, and that they should not be redacted to remove the names and personal information of the tipsters.

In a statement, Chris Nuelle, a spokesman for the Attorney General's Office downplayed the office's involvement in the county's decision-making process.

"We received an informal inquiry from a lawyer for the County, asking if we agreed with their interpretation and possible application of the law," said Nuelle. "There was no formal request for an AGO opinion, nor was it client communication — it was essentially a favor asked of us for a 'second opinion.' While we were mulling the County’s informal request, they decided on their own to release those materials before we got back to them. We did not formally advise or issue an opinion to the County on the release of these materials."

St. Louis County clarified they did seek input informally.

"We did not ask for a formal written opinion. When we were told over the phone that not releasing them could be a violation, we proceeded. We’d rather be too transparent than run afoul of the law," said Doug Moore, St. Louis County Spokesperson.

The fallout

Ultimately the 900 emails ended up on social media with many sharing and commenting that the tipsters were snitches, with some threatening to call employers and get the tipsters fired.

"Unfortunately you see a lot of in a hyper-partisan election environment and unfortunately this issue about whether or not to follow safety orders, whether or not to close, difficult choices between lives and livelihoods, is an extraordinarily partisan issue that starts at the top of the leadership of our country and filters right down into local government," said Page.

How did the list get online?

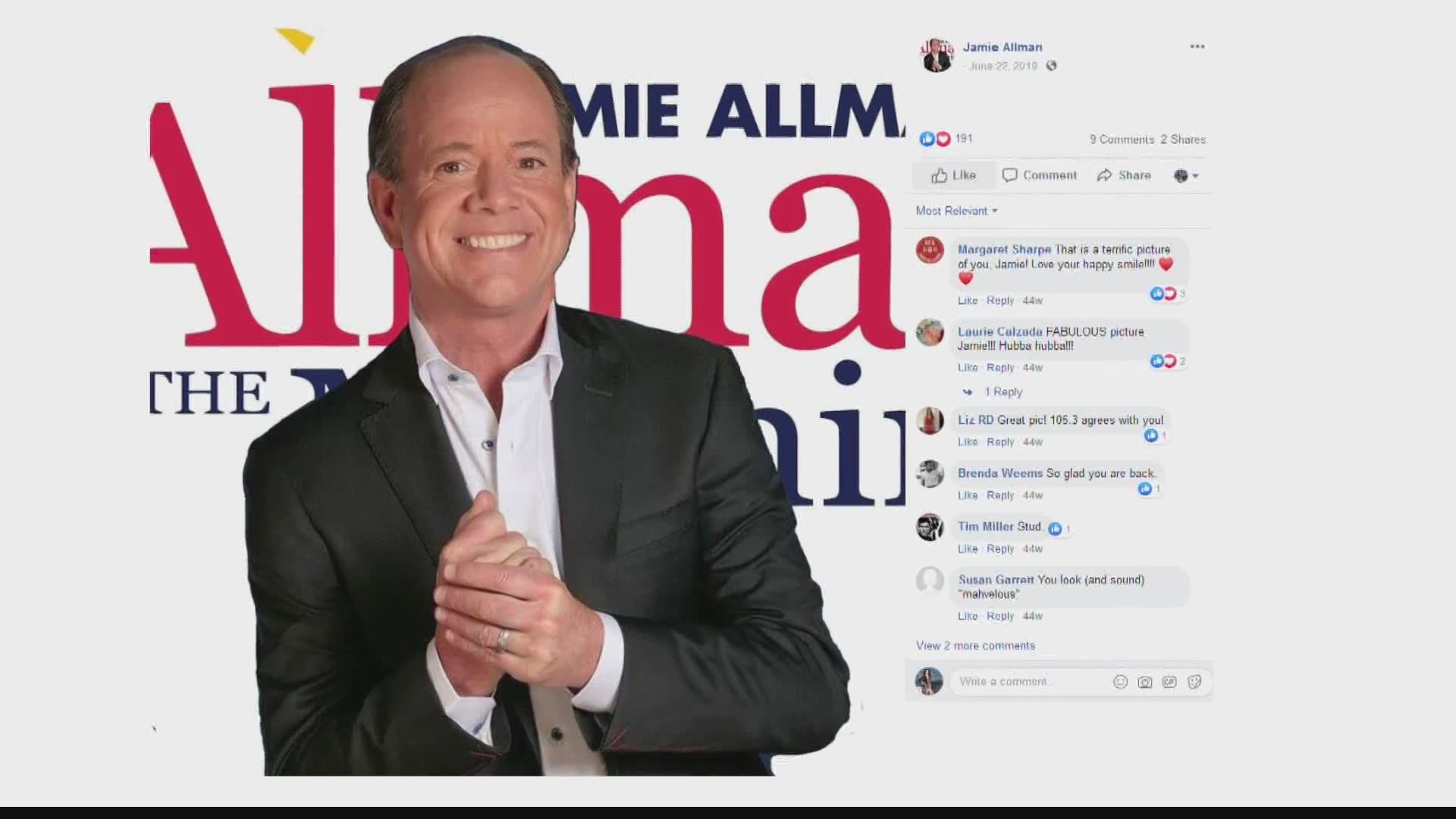

The I-Team learned the emails were only originally released to one person in early April. A sunshine law request filed by the I-Team revealed talk show host and former ABC 30 anchor Jamie Allman made the request on April 3. It's unclear when he received the records.

We reached out to Allman to find out how the list ended up online. He directed us to his online radio show, where he admits releasing the information.

In an email, a county spokesperson told us: "Of course all of this could have been avoided if the journalist who asked for the records had not used them for ill-intent, which certainly seems to be the case here."

County Executive Page said he doesn't expect tipsters have much to worry about.

"I do not, and would not expect anyone to retaliate against someone who made a complaint or identified a concern in good faith and I think there are many rights for people who are retaliated against," said Page.

When pressed for more context on what those rights entail, Page's spokesperson elaborated, stating: "if someone is threatened, they can contact the police or file an order of protection."

Page said other tips like those sent to the police or 911 would not be treated the same.

"Information related to public health orders and information related to stuff within the police department, those are treated differently," said Page.