ST. LOUIS — Flatten the curve. Social distance. Shelter in place.

Those phrases entered our collective vocabulary in March 2020 when the first coronavirus cases were reported in the St. Louis area and, public health and government officials instituted emergency orders aimed at reducing the spread of the virus.

A study published Wednesday by the Washington University School of Medicine says those measures likely saved the lives of thousands of people.

A delay of even two weeks in issuing local public health orders could have increased the number of deaths almost sevenfold in the city and county, according to the university's data analysis.

St. Louis area leaders enacted the safety measures, in part, due to the cases in New York and Boston.

"Whether a similar situation would have happened in St. Louis is not obvious,” said lead author Elvin H. Geng, MD, a professor of medicine. “Some may argue that because the same thing didn’t happen here, it could never have happened here and that, therefore, early social-distancing policies were an overreaction.

"But our data suggest that a large number of deaths due to the pandemic was indeed possible in St. Louis, and therefore, the early implementation of public health orders helped prevent the number of deaths that cities such as New York and other places experienced.”

The researchers used a model to examine what was likely to have happened if the epidemic trajectory in St. Louis early in March had continued without the enactment of public health policies for another one, two and four weeks, according to a press release from the university.

With the public health orders in place (bans on large gatherings, closures of bars, restaurants, schools and shelter-in-place), St. Louis area hospitals saw a total of 2,246 COVID-19 hospitalizations and 482 deaths attributed to COVID-19 by June 15, 2020.

If the orders had been delayed two weeks, the researchers’ modeling indicates that the city and county likely would have seen 3,292 deaths by June 15 — a nearly sevenfold increase over what was actually recorded in the first three months of the pandemic. In the two-week delay scenario, the model predicts an increase in cumulative total hospitalizations by June 15 from the actual number of 2,246 to an estimated 19,600 — a nearly ninefold increase.

St. Patrick's Day celebrations were amongst the first events to be cancelled last year, organizers hoped that dispersing those crowds -- sometimes thousands deep -- would help with our case counts. It was an 11th hour call that organizers call a hard decision, though ultimately the right one.

"We feel good," Jim Mohan, a Dogtown parade organizer, said. "At the time, we weren't sure what was going on, but we based it on what we thought was the best information we had and an abundance of caution too."

Even a one-week delay in public health measures would have increased hospitalizations and deaths, with an estimated 8,000 hospitalizations and 1,300 deaths by June 15, under the modeling scenario.

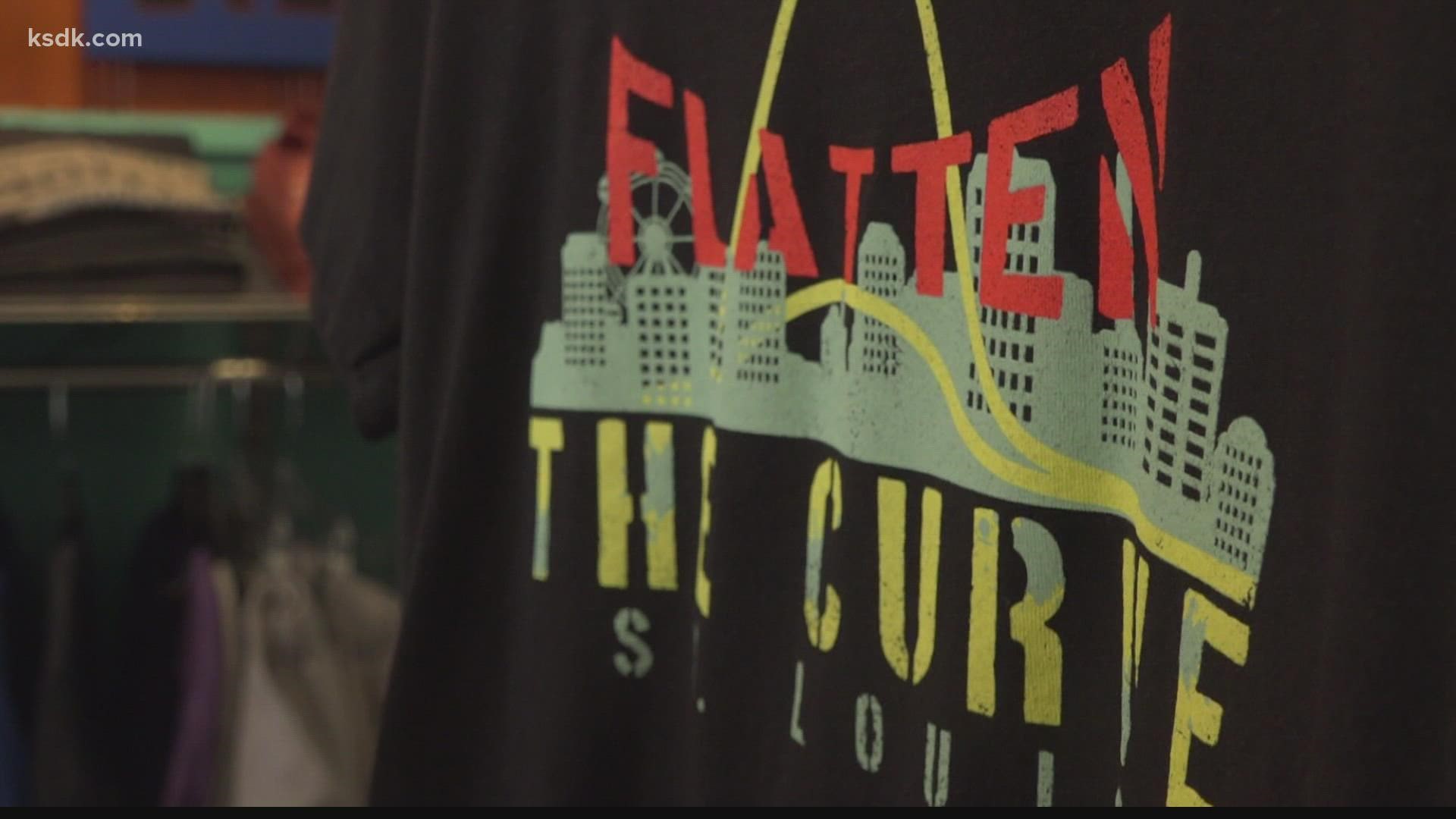

At STL Style, owners were quick to get on-board with the message to "flatten the curve," printing t-shirts with the phrase that became one of their top sellers in 2020.

"There is no other city that is as right for exploring that as St. Louis with our Arch. So we just turned it into a visual and voila," co-owner Jeff Vines said, motioning to the design that features the soaring curves of the Arch over a lower curve meant to represent suppressed COVID case trends.

"Not only did we 'flatten' the curve, but you could also say we crushed the curve," Geng said.

The researchers also estimated how the delays in enacting public health orders might have played out if the public had voluntarily changed its behavior.

"If the public had changed its behavior enough to cut viral transmission by half — an optimistic scenario — a two-week delay still would have resulted in an estimated 8,090 hospitalizations and about 1,400 deaths," the release said.

As COVID-19 cases rose in other parts of the country, data from cell phones in the St. Louis area showed the public made no changes in mobility before the city and county orders.

"A pandemic is like a big ship; it takes time to change course," Geng said. But as the virus ramped up, early social distancing policies in St. Louis mitigated it just before it really exploded.”

Geng performed this analysis with colleagues at Washington University, BJC HealthCare, Saint Louis University, Mercy Health and elsewhere, including senior author Maya Peterson, MD, PhD, of the University of California at Berkeley, and lead programmer and co-author Joshua Schwab, of the University of California at San Francisco.

The researchers said they hope that other public health officials across the country will be able to use it to inform pandemic responses in their communities, the release said.

The study was published on Sept. 1 on JAMA Open Network.