ST. LOUIS — Chicago reported Monday that 70 percent of people who've died from coronavirus in the city were black.

It's a disparity that's starting to emerge in St. Louis, too.

"So, what you have is a whole bunch of people, who can't breathe well enough on their own, who are on ventilators and the overwhelming majority of them are black and brown folks," Dr. Laurie Punch said.

Those are the doctor's observations from working the overnight shift, treating COVID-19 patients in the ICU at Christian Hospital Northeast in north St. Louis County.

The doctor said some coronavirus patients being treated there have died. The sickest of the others haven't recovered yet.

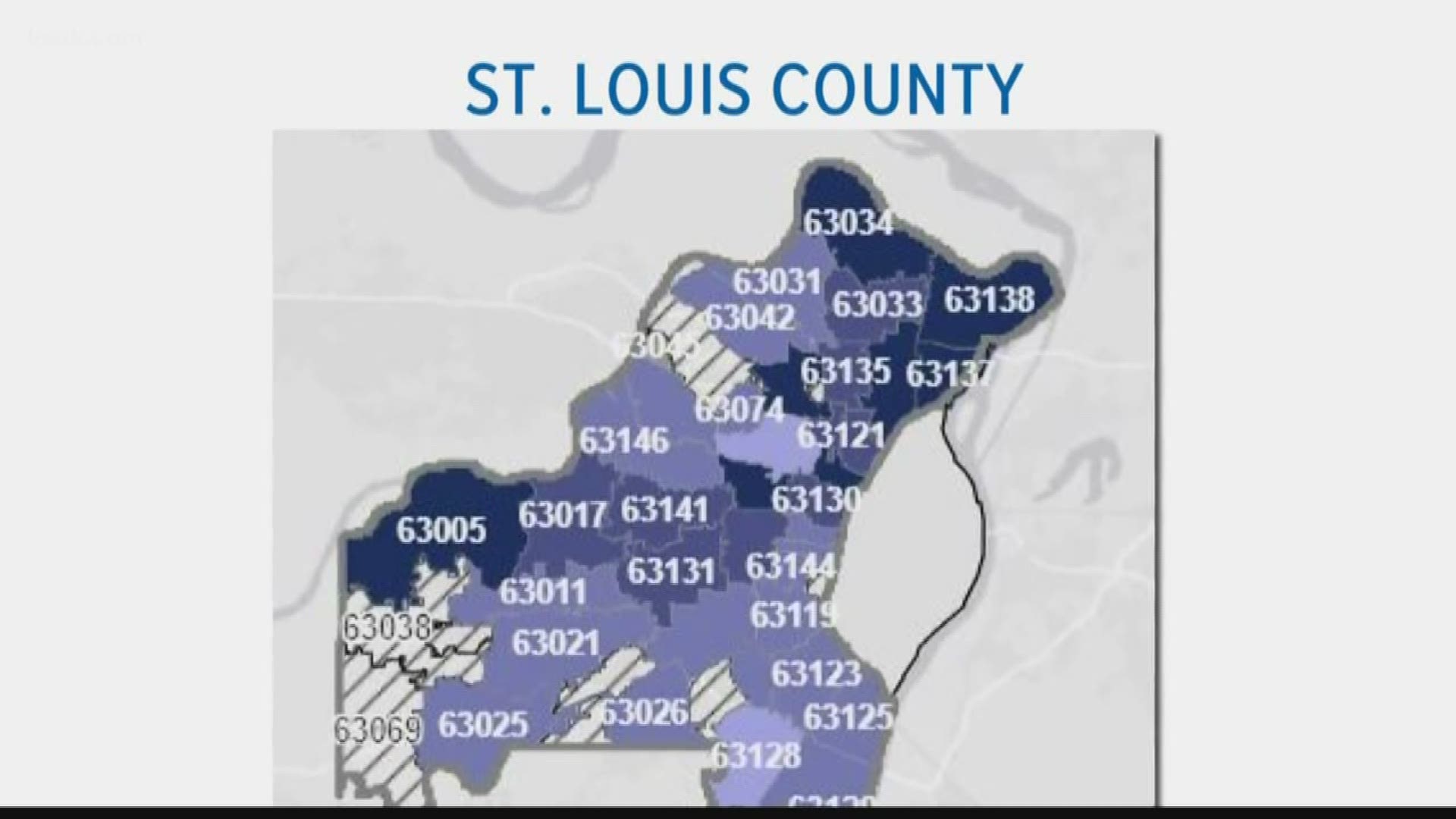

Dr. Punch said there are three times as many coronavirus cases in the predominately black north St. Louis and north St. Louis County areas as there are on the south side.

Both the city and county track cases by ZIP code, and their maps show a higher concentration of cases in north city and north county zip codes.

"There's an inescapable risk for people in north city and north county because of those deep, historical norms that basically have created this scenario where life is not supported," Punch said.

According to data from BJC Healthcare, African American individuals have 2.5 times the odds (loosely interpreted as "risk") of being admitted with a COVID-19 diagnosis. African American patients have 2.2 times the odds of being transferred to the ICU once admitted to the hospital. African American patients have nearly 4 times the odds of being placed on a ventilator.

A BJC spokeswoman said those statistics are based on a small number of patients in the health care system and "do not represent the outcomes of a rigorous study of such factors, but rather, are a snapshot of what we are seeing in our data so far."

Access to basic needs, like food and transportation, isn't guaranteed. For many families, physical distancing isn't even possible, Punch added.

Punch is also a trauma surgeon working in communities to fight gun violence. Punch runs Stop the Bleed, a program that teaches people how to stop bleeding in gunshot victims and said violence and the virus follow similar patterns.

"I've seen what bullets do to us. I'm worried the virus will do even more," Punch said.

So to stop the virus, Punch is calling for education outreach, more screening and a plan to stabilize daily life to help disadvantaged communities endure.

"I don't think it's going to go away soon," Punch said.