Until then, the St. Louis Argus, founded in 1912, was the main media eyes and ears of the Black community.

In 1928, Black St. Louis residents lived and conducted business in a “separate, but equal” city, where access to everything from neighborhood lunch counters was dictated by skin color. Jim Crow laws reigned and Black St. Louisans were calling for a second paper to challenge the status quo and represent Black interests. John Levy Procope, a local businessman, took charge of gathering the needed share-holders for the new paper.

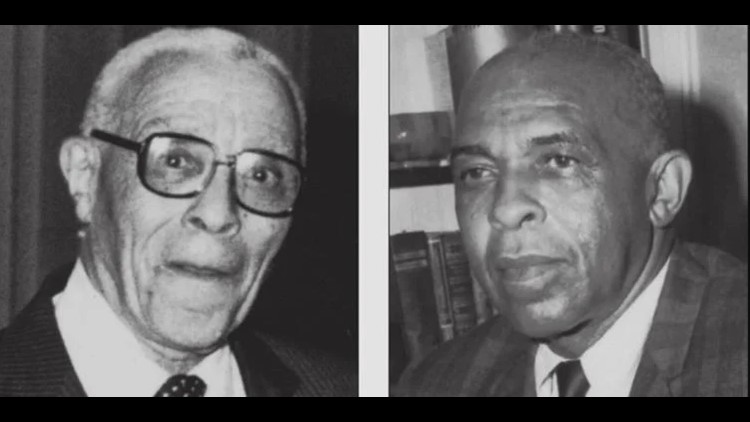

Procope coaxed his father-in-law, veteran newsman A.N. Johnson, to move from Baltimore to St. Louis to help facilitate the creation of an alternative Black voice in the city.

But the would-be share-holders of the St. Louis American, who held their first meeting at the Peoples’ Finance Company in 1928, could not have predicted the economic fallout after the start of the Great Depression the following year. The newspaper’s original investors, many of St. Louis’ most successful Black professionals, boldly put their money and credentials behind the paper’s vision.

A young lawyer and St. Louis newcomer, Nathan B. Young Jr., used his legal experience to officially incorporate the fledgling newspaper, then signed on as editor.

Originally from Tuskegee, Ala., Young reportedly grew up next door to Booker T. Washington. His father Nathan B. Young Sr., was a prominent educator who became president of Florida A & M University and later Lincoln University. Charles Udell Turpin, Missouri’s first Black elected official and owner of the Booker T. Washington Theater at Market and 23rd St., also signed on as a shareholder. Turpin’s theater was one of the first owned and operated by African Americans in the country and was rumored to be the site of Josephine Baker’s first performance.

Arguably one of the most renowned St. Louis citizens, Homer G. Phillips, a popular lawyer and civic activist, bought stake in the paper. Phillips was best known for his work with the city alderman in the early 1920’s to pass a bond issue to improve the city’s public works system and build a hospital to serve the Black community. The hospital, which opened several years later after Phillips’ untimely murder, bore his name. Other investors included the

Rev. Douchette R. Clarke, rector of All Saints’ Episcopal Church; Richard Kent, owner of the St. Louis Stars, world champion Negro baseball team; and Sumner High School teacher Robert P. Watts. Ruth Miriam Harris, former president of Stowe College, later Harris-Stowe State University, lent her support to the venture, as did Dr. Thomas A. Curtis, a Black dentist and the first Black president of the St. Louis branch of the NAACP.

Many of the American’s original investors have later been included in editions of Who’s Who in Colored America. In St. Louis, they represented the cornerstones of the Black community and provided the foundation of what would become the city’s top Black newspaper.

Civil rights champion

The St. Louis American’s first issue on March 17, 1928, sold out of its 2,000 copies with the headline “Pullman Porters May Strike.”

With its first edition, the paper aligned itself with the struggle for equal rights for the Black citizens and diligently covered the political and civil rights issues of the day. In a 30th anniversary edition of the American, then-editor Nathan B. Young Jr. reported the hard fight of the Pullman Porters, the first Black labor union, for recognition around the country and especially in St. Louis.

The American’s coverage of the Black porter’s incited the Pullman Company to buy full page ads in other papers in opposition to the Black union, Young said.

On two occasions, the Pullman Company bought all the copies of the American on newsstands, “not an entirely unkind act since the sales bonanza came in well,” Young said, as the paper depended heavily on circulation income. Although the Black union lacked the funds to buy ads, the American dutifully presented coverage of the group’s organizing efforts. “It was the first, but by no means the last case where the young American found itself on the ‘right side’ that had little or no money to back it,” Young said. During the “Don’t Buy

Where You Can’t Work” campaign, the American printed the names of stores and companies that would not hire Black employees. The editor received constant warnings of retaliation for the campaign, including that “Negroes would stand to lose the good jobs they already had,” Young said. No such counter move occurred. After two years of the campaign, which included boycotts of neighborhood stores, many began to employ Blacks. Young reported that even the St. Louis Dairy Company hired “colored milk wagon drivers.” Considered radical at the time, the paper’s assertive coverage of the campaign and various social issues raised awareness and even mobilized citizens to take a firm stance on issues. Despite its position as the “other” Black paper in the city, the American quickly gained a reputation of speaking on behalf of Black people in St. Louis.

“The Argus has more circulation, but the American was the civil rights fighter,” said Fred Sweets, son of Nathaniel Sweets, Sr., publisher of the American for nearly four decades. Serving the same community, Fred Sweets said, the papers worked side by side rather than in competition with each other. Fred Sweets said he remembers walking with his father to the Argus’ offices just blocks from the American’s old address at 11 N. Jefferson.

“My father was often personally involved in many of these movements so they received more coverage in the paper,” Sweets said.

Riding high on the success of their new enterprise, the American’s staff and founder were ill prepared for the economic disaster and tough times that lay ahead.

‘Sweet’ start

The depression that followed Black Tuesday in 1929 triggered a mass exodus of the American’s shareholders and resignation of its co-founder,

A.N. Johnson. Nathan B. Young Jr. seized more responsibility. “I had kept on as the editor and was now drafted to keep the paper going,” he said.

Young called his father Nathan B. Young Sr., then president of Lincoln University, for advice.

Within three days, Young Sr. had recruited Nathaniel A. Sweets Sr., a recent Lincoln graduate who would adopt the American like a member of his

family and keep the paper in circulation for the next 45years. Originally recruited as an advertising manager, Sweets quickly rose to business manager and publisher of the paper, buying out Young’s shares in 1932. Young stayed on as a writer, and Fred Alston joined the staff as art director and cartoonist.

Under Sweets’ direction, the paper sputtered through the Great Depression of the early1930s and its aftermath. Despite tough economic times, Sweets and staff continued to provide coverage on social issues of the day and created promotional events that generated buzz around the city and fostered loyalty to the paper.

“The St. Louis American Home and Cooking Show was a big deal and it was a lottery for the Black community,” said Ellen Sweets, daughter of Sweets Sr. and recently retired writer for the Denver Post.

“Everybody from the community came out and we gave away food and door prizes, and everybody came out on the night they gave out a stove.” The attendance prizes for the cooking show included a1928 Hudson Automobile.

American coverage of the event reports that more than5,000 people attended one of the shows and local companies like Laclede Gas Co. and National Food Stores offered sponsorships.

“My father was the master promoter,” said Fred Sweets. “The paper never made a huge profit, but the events he organized helped support the paper’s losses.”

Fred Sweets fondly remembers taking the train from Union Station to Urbana, Ill. as part of the St. Louis American Football Special.

“For the cost of a subscription and a bit more, he could charter a train and, for a flat fee, you would get a train ride, tickets to a University of Illinois game, and a light lunch on the ride there and a gourmet meal coming back,” Fred Sweets said. Nathaniel A. Sweets Sr. also hosted and spun records during the St. Louis American Breakfast Hour, a talk show featuring local personalities that was broadcast from the

Southern Kitchen restaurant on Delmar Ave. The St. Louis American Cab Company, sported the paper’s logo with dark and light green stripes on cabs across the city.

In those early years, strong writers and personality columnists helped increase the paper’s popularity and attracted loyal readers. Melba A. Sweets former contributing editor and wife of Nathaniel A. Sweets Sr., co-wrote the paper’s popular gos-sip column with long-time friend Thelma Dickson.

Sweets said her proudest memory was a letter she received from Langston Hughes about how much he enjoyed the column while passing through St. Louis.

“Back in those days, on Monday nights, folks our color could go on the boats on the Mississippi River, Melba Sweets said. “So we would talk about who was there and what they were wearing and who they were with.”

Fiery columnists such as Henry Winfield Wheeler led the attack on “half-hearted civil righters and Uncle Toms,” Young Jr. wrote. Wheeler’s column “The Spider’s Web,” a forerunner of the Political EYE, was dedicated to outing questionable politics and politicians in the city. Perhaps the paper’s most important find in the late 1930’s was a man-about-town, Bennie G. Rodgers. Rodgers first job with the American was for promotional work, but after serving in WWII, he returned to work in circulation in 1945 and later became the city editor of the paper. Rodgers mentored many of the first-rate journalists who passed through the American over the years.

“He was a consummate newspaper man,” said Fred Sweets, who went on to work as director of photography for the Associated Press in Washington, D.C. That man did nearly every job there was to get the newspaper into print,”

Ellen Sweets said. She fondly remembered the “cussing and shouting matches” Bennie had with visitors and other staff in the paper’s editorial offices.

“Bennie would bait people with comments that he knew would send them off, and he yelled at everybody, including me.”

Thumbing through the dusty worn pages of the archived copies of the American is like reading the history of race relations in St. Louis. While Black papers around the country struggle to remain financially viable, though rarely profitable, they continue to give voice to the Black community.

“My father’s vision was to give a voice to the Black community that was lacking and bring them information they could use,” Ellen Sweets said. “The St. Louis American carried news tailored to the Black community and anybody who wanted to know about it."

To watch 5 On Your Side broadcasts or reports 24/7, 5 On Your Side is always streaming on 5+. Download for free on Roku or Amazon Fire TV.

5 On Your Side news app