ST. LOUIS — The experiences of dozens of Missourians are showing the impact of the disorganization at the city tow lot, described in a St. Louis City comptroller’s audit released this week.

For Louise Schneider in Jefferson County, it was the loss of her dream car.

“It was one I had always wanted, and you don't find them every day,” Schneider told the I-Team. “I hadn't titled it yet. It wasn't even 30 days that I had this car and it was taken.”

Larry Lacavich lost the tool he needed to run his business when his truck went to the city tow lot.

“That was my main bread and butter,” said Lacavich. “It was already paid for.”

Both vehicles were stolen, and then they were recovered in St. Louis City. Police sent the cars to the city tow lot.

City ordinances say the tow lot will notify the owner of any car they receive. Then, the owner can pick up a recovered stolen car for free within 72 hours. If the car stays on the lot for 30 days, the city can auction it off.

Neither Schneider nor Lacavich would ever get their cars back.

Schneider said she didn’t even know the city tow lot had her car until three days before the city auctioned it off.

“I was never contacted or anything about the car,” Schneider said. “I come to find out that they actually contacted the previous owner of the vehicle.”

She said that the tow lot employees considered her 72 hours to pick up the car to be long past, and her car was set to go to auction.

“When I had contacted them, it was already up to, I believe it was eight hundred or nine hundred dollars to get it out,” said Schneider. “They auctioned it off for $750.”

Todd Waelterman, director of operations for the city of St. Louis, said when possible, the tow lot works to reunite auto theft victims with their property. In Schneider’s case, he said, they did what the law required.

“We didn't send it to the wrong party. We sent a note to a registered owner, OK, at the time, and that's what the state statute says to do,” Waelterman said.

Lacavich tried to retrieve his truck just 48 hours after he received notice.

“Called them Monday evening, and we just said we'll go Wednesday,” he said. “They said, 'Oh, the white F-250. Oh, that's getting auctioned off on such and such date right now.’ They already had it on the board that quick.”

When Lacavich tried to retrieve the truck, he had everything the city ordinances say an owner needs to get a vehicle out of the tow lot. Tow lot employees disagreed.

“I had the original title signed over to us by the used car lot. And it was notarized. A notarized bill of sale from the used car lot that we purchased the truck from,” said Lacavich.

To complicate things, Lacavich had also not yet registered his vehicle in his name.

“I'm bad about doing stuff like that. I'll be honest. The penalty shouldn't be, you know, losing your car. I lost it to somebody else, not to the state, that the taxes were owed to,” he said.

City ordinance 17.56.190 says that a vehicle owner needs to bring proof of their identity, proof they own the car, and proof that any traffic or parking fines or summons have been cleared up in order to get their vehicle out of the lot. It does not mention that the vehicle must be registered or that the owner must be in possession of valid registration.

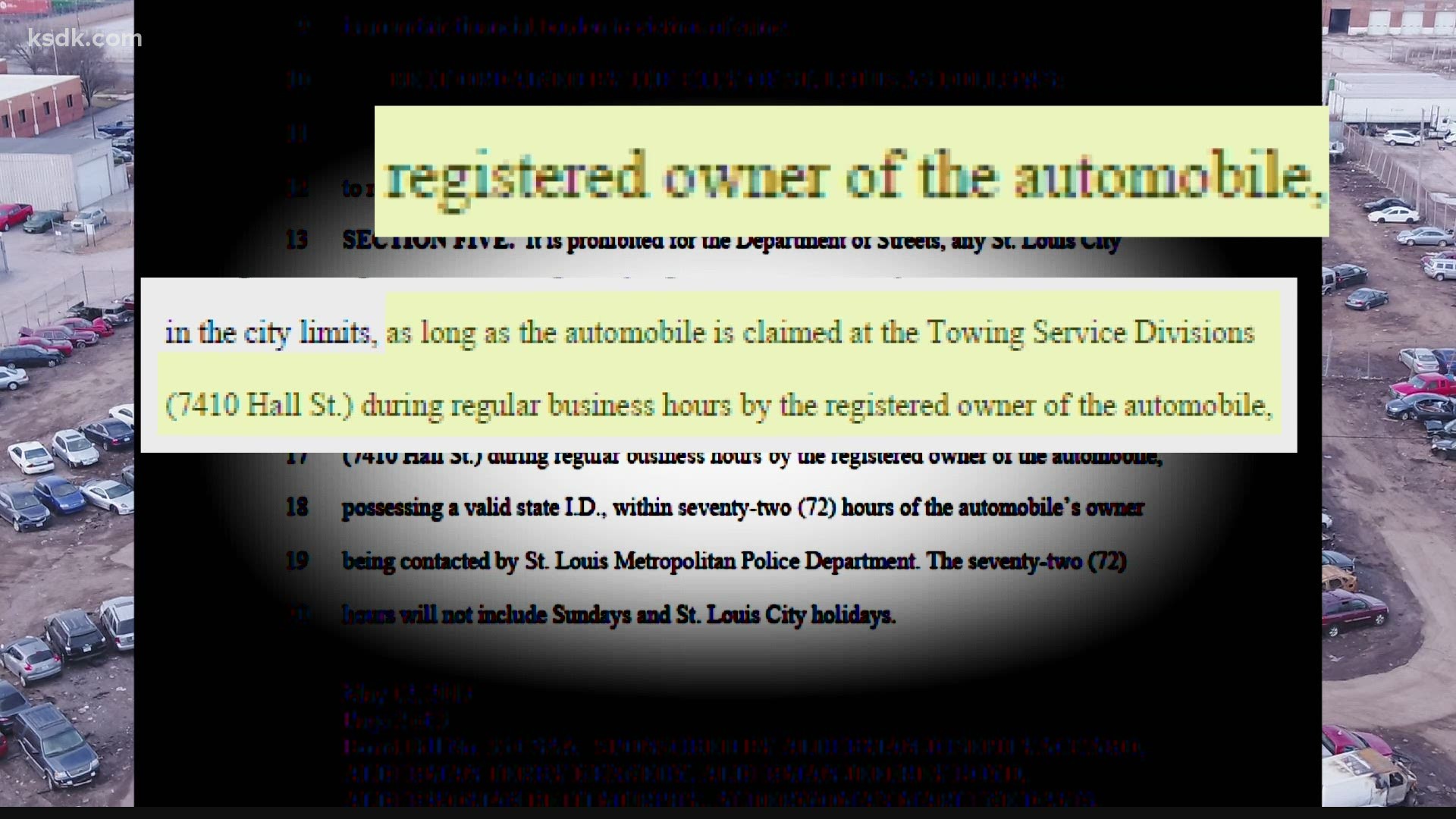

Waelterman pointed to the city ordinance describing how victims of car theft can recover their cars within 72 hours for free, which specifies that the “registered owner” may retrieve the vehicle.

“People nowadays, you can make any document up you want to build a sale. It's easy to, you know, phony a seal on it,” Waelterman said. “We deal with millions of dollars for the vehicles, every year, so we in the state feel strongly that the registered owner is documented by title action.”

“Why do they get it? They stole it,” Lacavich said.

Schneider felt the same way after her car was auctioned off:

“I would like everybody to know that what happened, it was crooked and it was wrong.”

Waelterman believes the solution lies in state legislation that would charge car buyers their sales tax and plating fees before taking possession of the car. Missouri legislators have attempted to pass legislation to that effect dozens of times before.

“Put it in the bill of sale and do it all at once,” said Waelterman. “That would really help this whole registration deal.”

In the comptroller’s audit of more than two years of documentation at the Auto Towing & Storage division, an auditor discovered several problems that affect auto theft victims directly.

The special review audit, prompted by tips to the city’s fraud hotline, found that 82% of vehicles brought to the lot with a police hold “did not have the proper documentation to be correctly processed.”

A police hold applies to towed vehicles that were recovered after being reported stolen, giving police the opportunity to process the car for evidence. The audit stated that mistakes in the documentation included missing paperwork, “forgetting” to record holds or releases, and information entered incorrectly into recordkeeping systems.

The audit adds that incorrect documentation means recovered vehicles could be lost on the lot or sit indefinitely because vehicles with police holds and no release cannot be auctioned off or returned to their owners.

“I'm a single mom of three boys, and that was the only vehicle I had,” Schneider told 5 On Your Side. “It was heartbreaking.”

Lacavich is still reckoning with the cost of getting another truck. “To replace it, it would probably be, as clean as it was, probably close to seven thousand dollars,” he said.

When asked about the impact of reported police holds recordkeeping issues at the city tow lot, the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department wrote, “The department is not responsible for administrative processes at City Towing.”

The suspect accused of stealing Schneider’s car faces a tampering first charge in Jefferson County for the theft.