ST. LOUIS — Nicholas Gilbert’s death in St. Louis police custody changed the way the department supervised prisoners at area stations.

Now, it could have widespread legal implications and is among a growing number of deaths involving restraint in police custody nationally.

The 27-year-old died after about 6-8 officers used a technique called prone restraint while he was handcuffed to try and stop him from trying to take his own life, and, from hurting the officers who went into his cell to stop him, police said at the time.

Gilbert’s parents dispute the police summary of his death and the autopsy, which concluded Gilbert’s manner of death was “accidental,” and the cause of death was “Arteriosclerotic Heart Disease exacerbated by methamphetamine and forcible restraint.”

They have sued the city and the case made it all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled in their favor earlier this summer sending it back to the lower courts to reconsider the case.

The move means the case could set a national precedent on how lawsuits involving prone restraint deaths are handled and challenge whether qualified immunity should shield officers.

Awareness about the dangers of prone restraint ballooned following the very public death of George Floyd in Minneapolis, which was caught on a bystander’s cellphone and showed an officer kneeling on Floyd’s neck and back while he was in the prone position and handcuffed.

Investigations by 5 On Your Side’s sister stations across the country found at least 120 people died while they were restrained in a prone position.

Gilbert’s mother, Jody Lombardo, said she’s optimistic about how her son’s case could challenge qualified immunity.

“They took a life unjustly, violently, and they should answer to that,” she said.

But police offer a different story.

A struggle

Gilbert was arrested for trespassing and an outstanding traffic ticket in December of 2015. His mother said he was rehabbing a property when someone called police believing he was trespassing.

Police took him to one of the city's area stations along Sublette Avenue.

Police said he was under the influence of some type of drug and tried to hang himself with a sweatshirt inside a holdover cell there.

One officer tried to untie the sweatshirt, and he became combative. Between six and eight officers then used a technique called prone restraint while he was handcuffed to try and stop him from hurting them and himself, according to then Police Chief Sam Dotson.

During the struggle, Gilbert fell and hit his head on a bench, Dotson said.

Gilbert’s mother disagrees.

“Too many men ran in there, handcuffed him, leg shackled him, battered him around and now he's dead,” she said. “And they say they did nothing wrong.”

Following Gilbert’s death, Dotson installed cameras inside all of the department’s holdover cells so every interaction could be recorded.

He also went to the morgue to view Gilbert’s injuries after hearing Lombardo claim officers beat her son during the struggle.

Afterward, he said he found Gilbert’s injuries to be consistent with the officer’s statements regarding a scuffle they had while trying to stop him from taking his own life.

A long legal battle

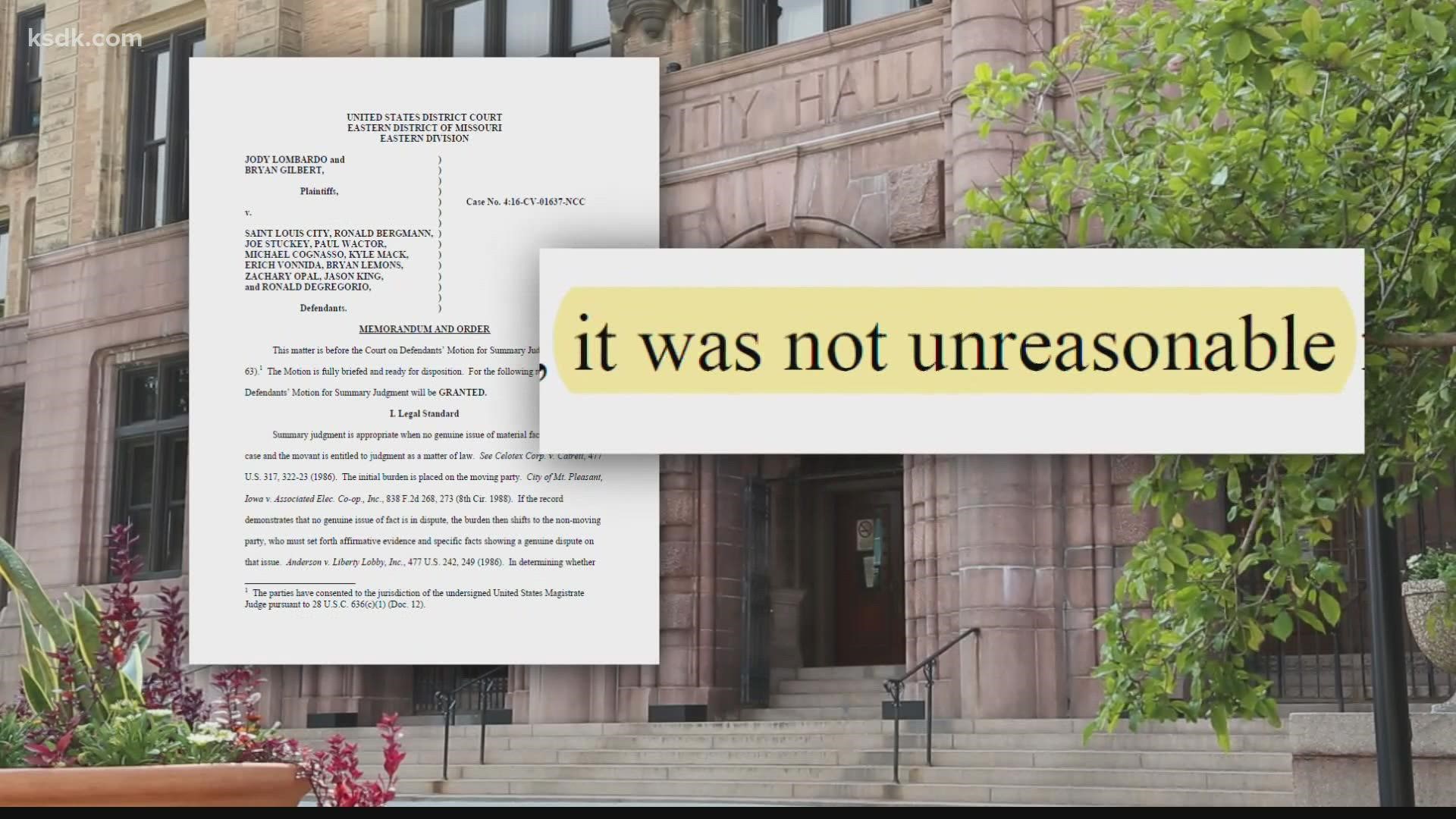

Gilbert’s parents sued the city, but judges kept dismissing the lawsuit citing qualified immunity.

It’s a law that protects police officers from being held liable in civil lawsuits.

And it’s been controversial in recent months as critics say it shields officers from being held accountable.

But it can be overcome – should a plaintiff prove an officer violated a person’s civil rights during their use of force.

In Gilbert’s case, the judge who granted the officers qualified immunity noted, “qualified immunity does not depend on whether the individual’s actions were ‘in fact’ innocent but, rather, ‘the key’ is whether the officers reacted reasonably to the circumstances as they appeared to the officers.”

Lombardo’s attorneys argue Gilbert’s resistance happened because he and others who are held prone experience “air hunger,” in which they struggle because they can’t breathe.

In its dismissal, the court assumed that “Mr. Gilbert’s actions were innocent, that he was not ignoring commands or being violent, and that his actions were based on ‘air hunger.’ Even so assuming, however, the court finds that it was not established as a matter of law that the officers should have interpreted Mr. Gilbert’s actions of kicking, thrashing, and otherwise fighting as ‘air hunger’ instead of resistance. Instead, as will be discussed more below, courts in this and other circuits routinely interpret such actions as objectively reasonable evidence of resistance.”

St. Louis University Associate Professor Greg Willard said the courts now have a difficult decision ahead.

“I think those who are looking at the Lombardo case as the flag bearer for significant reform for qualified immunity, I think that optimism on that case is misplaced,” he said.

Willard said qualified immunity is vague, and said it’s up to lawmakers, not just the courts, to decide its future.

“It’s Congress that needs to wrestle with this and come up with a mechanism that there can be a much broader consensus on a qualified immunity,” he said.

In its 6-3 ruling sending the case back to the Eight Circuit for a new review, the high court cited warnings about prone restraint from the Department of Justice dating to the 1990s.

It recommends “officers get a subject off his stomach as soon as he is handcuffed."

The ruling continued: “Record evidence shows that officers placed pressure on Gilbert’s back even though St. Louis instructs its officers that pressing down on the back of a prone subject can cause suffocation,” according to the ruling. “The evidentiary record also includes well-known police guidance recommending that officers get a subject off his stomach as soon as he is handcuffed because of that risk.

“The guidance further indicates that the struggles of a prone suspect may be due to oxygen deficiency, rather than a desire to disobey officers’ commands.”

In depositions obtained by the I-Team, the officers involved said Gilbert was on his side for most of the confrontation, and only prone for a few minutes.

Lombardo’s attorney, Kevin Carnie, believes it was more like 15 minutes.

“St. Louis police know that it can be dangerous to hold someone in a prone position,” he said. “They claim that they instruct officers that they need to move them onto their side as soon as they can.”

No policy

St. Louis police have policies on several restraint tactics.

The I-Team obtained an email from 2007 advising against the use of chokeholds.

The city’s 2020 use-of-force policy advises police not to restrict a suspect’s breathing when deploying Tasers.

And, the St. Louis Board of Aldermen passed a resolution just this year banning chokeholds during an arrest.

But none of these actions address prone restraint or qualified immunity.

During Derek Chauvin’s trial in the death of George Floyd, experts blasted the tactic.

“It's just not appropriate to prone someone who is at that point, cooperative,” said University of South Carolina criminal law professor Seth Stoughton.

Barry Brodd, a former police officer, testified for the defense, saying the technique was the “safest” for both the suspect and the officers.

For Lombardo, consensus on the matter can’t come soon enough.

“I believe that the police got out of line, misbehaved, and killed my son,” she said.

Now, she will get her chance to prove it in court once more.