ST. LOUIS — Even after Christopher Dunn's exoneration following decades of wrongful imprisonment, Missouri's restrictive laws leave him with almost no support.

In just the last six years in Missouri, there have been nine people who have been exonerated after having been wrongfully convicted, according to the National Registry of Exonerations. Those people are Ricky Kidd released in 2019; Donald Nash, Jonathan Irons and Lawrence Callanan released in 2020; Kevin Strickland released in 2021; Keith Carnes released in 2022; and Lamar Johnson and Lamont Campbell released in 2023. The latest is Dunn, who was released in July.

They have collectively spent hundreds of years behind bars.

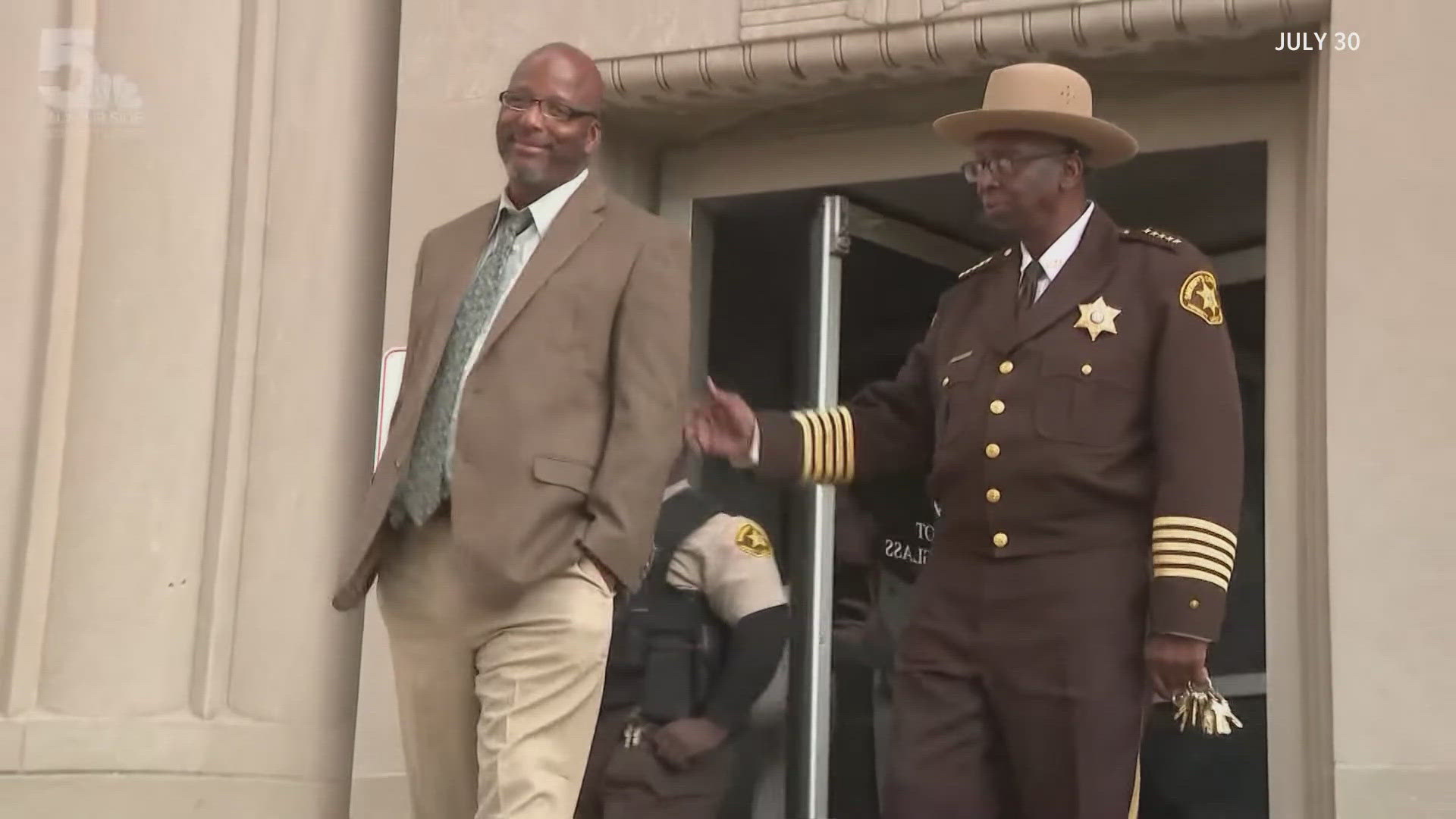

“It was torture," Dunn said on the steps of the Carnahan Courthouse in St. Louis on July 30. He spent 34 years in prison for a murder he had nothing to do with.

“When the system chooses to throw you away, you have to ask yourself if you're willing to just settle for it or are you going to fight for it," he said.

Lack of compensation funds

Since 1989, state and local governments in the U.S. have paid more than $4 billion to about 1,600 exonerees in compensation for their wrongful convictions and the time they spent in prison, according to the National Registry of Exonerations. Across the U.S., 38 states and the District of Columbia have enacted compensation statutes. But in Missouri, that compensation is rare.

As of today, 12 states do not have compensation statutes for people who have been wrongfully convicted. Those states are Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Delaware, Georgia, Kentucky, New Mexico, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota and Wyoming.

Missouri has a compensation statute that is limited to cases with DNA proof of innocence. It leaves most exonerees, like Dunn, with nothing.

In the last 35 years, 55 people with state court convictions in Missouri have been exonerated, according to the National Registry of Exonerations. In 27% of them, DNA was part of the exoneration process. Nationwide, 17% of all exonerations had DNA involved. A spokesperson with the National Registry of Exonerations said that the percentage is likely higher in Missouri because of the state’s long-standing resistance to non-DNA exonerations.

Tricia Rojo Bushnell with the Midwest Innocence Project said, “After stealing 34 years of Christopher Dunn’s life for a crime he did not commit, the state will give him nothing. Not compensation, not healthcare, not even a place to sleep. When the state makes such a tragic mistake, it has a responsibility to make things right."

"It's frustrating," said Kenya Brumfield-Young, a Saint Louis University professor.

In just a few days, Brumfield-Young will be teaching students about how wrongful convictions happen. Brumfield-Young said that in Dunn’s case, judges agreed there was not enough evidence to convict him. The court concluded that Dunn was not guilty and that he should not have been convicted. Brumfield-Young said the evidence available highlights Dunn’s innocence.

“We talk about things like eyewitness testimony, we talk about forensic errors and things like that," she said.

Brumfield-Young said errors lead to innocent people getting locked up, with no safety net if they're ever set free.

“And they get out and they have no support. They have, you know, very little money," she said.

Locked up at just 18 years old, Dunn lost most of his working years in prison, significantly reducing potential Social Security benefits.

Legislative pushback

Missouri Gov. Mike Parson (R) has argued that the financial burden for wrongful convictions should fall on the cities and counties responsible, not the state. In vetoing Senate Bill 189 in 2023, which would have expanded who is eligible for compensation for being wrongly imprisoned, Parson argued that local entities responsible for wrongful convictions should bear the financial burden. The governor has not made any recent statements on wrongful convictions or the Dunn case.

Attorney General Andrew Bailey, also a Republican, said, “The criminal justice system has to have a component of finality.”

“The juries of the state of Missouri under the Sixth Amendment have a right to participate in the process, and we should respect and defer to the finality of the jury’s determination," he said. "Too often, people forget about all of the evidence that was used to convict the defendant — the evidence the jury relied on — and the victims. And I want to make sure that we always honor the victims’ voices because they get forgotten."

A spokesperson told us the office reviews each case on an individual basis, taking into account the facts of each case.

Response

State Sen. Tony Luetkemeyer, R-Parkville, was the sponsor behind Senate Bill 189.

“If someone is wrongfully convicted, they should be compensated for their loss of liberty," Luetkemeyer said. "Right now, there’s a gap in the law where the only people entitled to compensation are those whose exonerations are based on DNA evidence. Today, there are few new DNA exonerations. The law needs to catch up with the times. I’m hopeful we’ll see legislation in the future to right this wrong."

State Rep. LaKeySha Bosley, D-St. Louis, expressed her disappointment over the 2023 veto of Senate Bill 189.

"We cannot provide Chris Dunn, Kevin Strickland, Ricky Kidd and countless others the time they lost by a miscarriage of justice, but we can make it so they are restored in a society they never had the opportunity to grow with." Bosley said. "They deserve to have health care, access to education, housing, financial literacy and more."

Michelle Smith, the co-director of the nonprofit Missourians to Abolish the Death Penalty said that "Gov. Mike Parson has stated that it's not the state's responsibility to compensate these individuals, which is ironic in light of the fact that his attorney general has fought against the release and exoneration of every single person who has been adjudicated innocent. It's sheer hypocrisy to declare that it's not the state's responsibility for an injustice that the state fights consistently to maintain.”

Criminal justice experts Peter Joy, a professor at Washington University in St. Louis, said compensation for those wrongfully convicted varies widely across the country, and Missouri ranks toward the bottom in several ways.

"Missouri does not pay anything to almost all of the wrongfully convicted persons," Joy said. "Missouri limits compensation to $100 a day for every day of incarceration, for a total of $36,500 a year, which is much lower than other states. For example, Kansas pays $65,000 a year and Connecticut pays up to $131,500 a year. ... Missouri does not actually pay the full amount but purchases an annuity. Someone exonerated in their 60s would have to live another 30 or 40 years to receive what is due to them."

Joy also noted that to receive compensation, a wrongfully convicted person has to give up the right to sue those responsible for the miscarriage of justice.

Looking ahead

For now, Dunn said he is focusing on the future.

“Sure, my youth is gone—I can’t ever get that back," Dunn said. “But if I hold on to the negativity, if I keep holding on to the past, I’ll never be able to move forward.”

He's moving forward, despite a life stolen and financial challenges that will last a lifetime.

The Midwest Innocence Project created a GoFundMe campaign for Dunn to help him re-enter society with some financial resources.

To get in touch with senior investigative reporter Paula Vasan, leave a voice message on 314-444-5231 or email her directly at pvasan@ksdk.com.