ST. LOUIS COUNTY, Mo. — Former Florissant Police Officer Michael Vernon believes the bullet-resistant vest he wore the night a burglary suspect shot him, leaving him paralyzed, failed to protect him.

Now, nearly 10 years later, he’s about to go to court with the company that made it – Safariland.

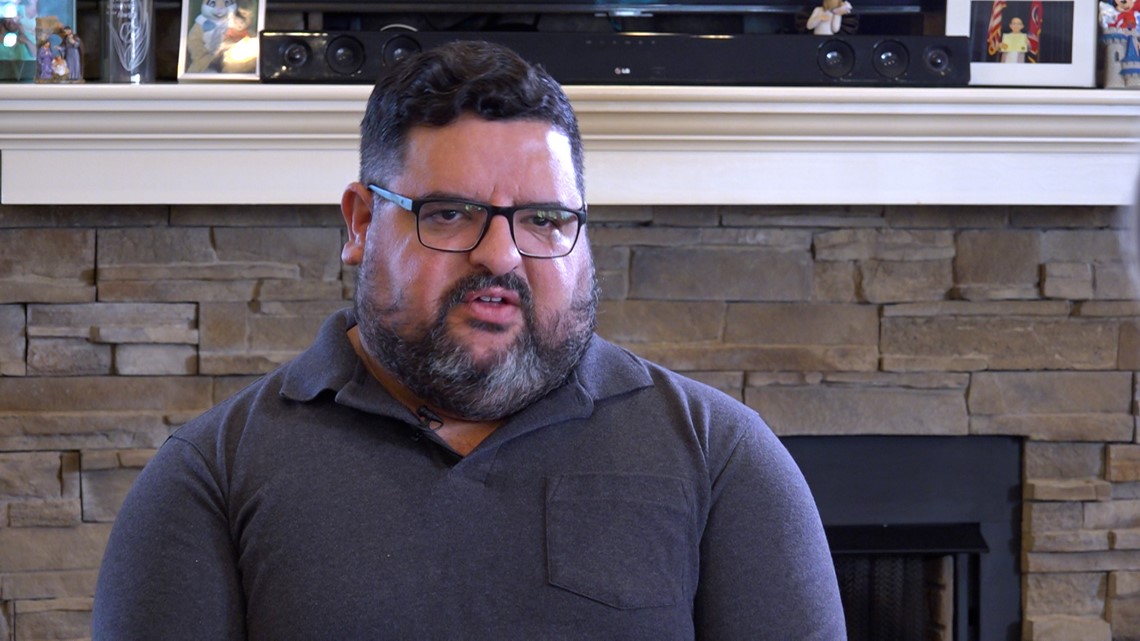

“My worries were, and still are, if the vest failed me, could it fail other officers?” he said in an interview at his home in Tennessee.

Representatives for the international company based in Jacksonville, Florida, did not respond to multiple emails from the I-Team seeking comment.

Attorneys for the company argue in court documents the vest couldn’t be "reasonably expected to stop the bullet" given its angle, size and where it struck the vest.

Vernon said the vest's faults go deeper than just the seams and the edges. It's about how an officer wears it.

Starting next week, Vernon and attorneys for the company will go to trial to decide the matter once and for all.

“It has never been an issue of money,” Vernon said. “It has been an issue of there is a fault in the way officers are being taught how to wear the vest or not being taught how to wear their vests.

“And that's my goal, to let what happened to me never happen to another officer again.”

'I couldn't move'

On May 28, 2012, Vernon was riding in his Florissant police patrol car when he heard a call about a burglary on his police radio.

He drove toward the business and pulled into the alley behind it. A pile of clothes caught his attention. He got out of his car, walked over to look at them and realized they had been there for a while, and probably had nothing to do with the burglary suspect still on the run.

“As I was walking back to my police car, Brian Cannon was hiding inside of a dumpster,” Vernon said. “He jumped out and I can still see, to this day, his face.

“I could still see the muzzle blast from the gun. And I remember getting shot and falling backwards. The creepiest, most eeriest feeling that I ever had lying there was that I couldn't move, but I could hear him on my right side and I thought, ‘He's coming back to finish the job.’”

Cannon kept running, eventually getting caught by Vernon’s fellow officers.

He was later convicted of shooting Vernon three times.

The first round struck Vernon's right side where the front and back flaps of his vest overlapped.

“It caused me to hunch over,” he recalled. “And while he was continuously firing from his weapon, another round went from the shoulder, shattered scapula of the lower part of my scapula and then lodged in the spinal cord at the T10 T11 area.”

It left Vernon paralyzed from the waist down.

“Some of the officers who responded to the scene when I first was injured believe that a bullet went through to the vest and that the vest had failed,” he recalled.

Florissant police commanders called Safariland.

Two high-level executives flew to St. Louis within days of the shooting to talk to the rest of Vernon’s fellow officers about what happened.

They showed the officers pictures of Vernon’s vest, said the bullet went in at an angle where the panels overlap on the side of his torso. They also explained the panels of the vest should be worn with the back panel tucked under the front panel – a technique Vernon said no one had ever taught him or his fellow officers.

“That was information given too little, too late,” Vernon said.

Filing a lawsuit

In June 2013, Vernon sued Safariland.

The company filed its answer to Vernon’s lawsuit in 2018.

In it, an attorney for the company wrote: "It is not reasonable or foreseeable that a .40 caliber bullet, given the direction and angle of the shot hitting less than one inch of the edge of the vest could be expected to defend the shot."

Attorneys for the company also called Vernon’s description of how the vest should be worn as a “mischaracterization of deposition testimony,” from their experts, and that, “no soft body armor would have defeated the angled edge shot involved in this case.”

Vernon and his wife, Farrah, had been married for only one year when he was shot. She was in medical school at the time.

“It took several months to even accept that you're paralyzed,” Michael Vernon said. “I mean, doctors tell you, but you're like, ‘Well, is there a chance?’

“I mean, my poor wife, she took every, every document, every image she could get from the hospital report and tried to spread it around her colleagues, like, ‘Is there anything we can do? Anything to make this better?’ And, you know, I think even she tried saying, ‘Yeah, I hope there's a chance,’ but, here I am, 10 years later, sitting.”

The couple moved to Dresden, Tennessee, to be closer to her family for support. It’s a town of about 3,000 people, and a 2 1/2 hour drive west from Nashville.

Vernon borrowed a vest from an officer he knew to demonstrate his point to the I-Team about how it should be worn.

His first move was to check the manufacturing sticker on the inside of the front panel.

It was made by Safariland in 2013 and had a five-year warranty.

“If you do the math, this vest expired four years ago,” Vernon said. “Something simple that could be fixed so easy.”

What other departments wear

The I-Team asked the two largest departments in the St. Louis area about who makes the vests their officers wear.

In St. Louis County, a company called PointBlank makes them and they’re replaced every five years. Florissant police – Vernon’s former employer – also uses PointBlank as part of a countywide bid.

Florissant Chief Tim Fagan issued a statement, which read: "I was not the chief at the time this occurred. To my knowledge, we did not stop using Safariland because of the shooting. There were two previous chiefs of police since that incident. We currently use PointBlank as part of a mutual procurement bid."

Safariland makes the vests St. Louis city police officers wear.

A St. Louis police spokeswoman wrote: "replacement depends on several factors, but they are warrantied for 5 years."

“I would put money on it, and I'm not a gambling man, that there are guys out there who are wearing the vest wrong and who are wearing vests that are outdated and they're not properly fitted,” Vernon said.

Vernon and his family are preparing to make the four-hour drive to St. Louis next week to attend the trial.

His wife finished medical school and is now a doctor.

They’ll be bringing their only child, 7-year-old Karston, with them. He was born two years after the shooting with the help of fertility treatments.

“My kid has only known me being in a wheelchair,” Vernon said. “He's never known me before, being able to walk.

"He'll never know what it means for me to go out in the middle of the grass to go run with him, to play soccer, to throw a ball.”

But Vernon wants his son to know him as a father who stands up for what he believes in.