'He just looked like a typical grandpa': Detective describes hearing confessions of alleged Cherokee Street stroll killer

Detective Sgt. Jodi Weber met with alleged serial killer Gary Muehlberg three times.

Barb Studt and Geneva Valle-Palomino spent a few quiet moments Monday morning, Sept. 19 looking for their sister’s final resting place.

They haven’t come very often to the St. Peter’s cemetery where 21-year-old Sandy Little was buried. It's too painful.

Her badly decomposed body was found in 1991 inside a makeshift box along Highway 70 in O’Fallon. They feared they would never learn who killed her.

The grave remains unmarked. It’s near the shadow of a statue of Jesus holding a baby sheep, called "The Good Sheppard." The cemetery donated the plot to the family after Little’s murder.

“Otherwise, who knows what would have happened,” Studt said. “Our family couldn’t afford a grave.”

But on Monday, they couldn’t think of a better place to spend their time. They were headed to a news conference in which prosecutors announced the identity of the man they believe tore apart their lives and those of at least four other families.

He confessed to killing five prostitutes between 1990 and 1991 that he picked up along what was once known as the Cherokee Street Stroll. The identity of one of the women remains a mystery.

In addition to thinking about the sister they never got to know in her later years, the women’s minds were also on the detective they say made the moment possible: O’Fallon Detective Sgt. Jodi Weber.

“I’m just so happy for Detective Weber,” Studt said. “She worked so hard on this case.”

Chapter 1 Taking the case

Jodi Weber was a fresh new face in the O’Fallon police detective bureau when she first heard the name Sandy Little in 2003.

It still haunted the veteran detectives, who talked about the young mother more than a decade after it happened. She had a 9-month-old son.

“It was just so horrific,” Weber said. “Who would do this?”

Little's body had been put inside a dresser missing the bottoms of its drawers. A wooden box had been built around it. A man on his way to work along Interstate 70, west of Highway 79, saw it on the shoulder in February 1991 and called police.

Inside, they found Little’s badly decomposed body. She had been missing since September and was last seen in the area of St. Louis where prostitutes once worked.

“I mean, there were 40, 50, 60 investigators looking at these cases,” Weber recalled. “I mean, they tried hard. They followed up on every lead possible.”

Investigators connected Little’s case to 19-year-old Robyn Mihan, whose body was found between two mattresses along Highway 61 and Highway E in Silex just a few months before Little's was.

Mihan had given birth to her second child two weeks before her murder.

In October 1991, the body of 27-year-old Brenda Pruitt was found inside a plastic trash can along the side of the road near Page Avenue and Interstate 270 in Maryland Heights. Her family had reported her missing on May 9, 1990.

In 2008, Weber said she asked her fellow detectives whether any of the evidence from the crime scenes had been tested for DNA.

“They said it hadn’t,” she recalled.

She went to Lincoln County to collect what she could from Mihan’s crime scene, too, and sent it along with evidence from Little’s case to the St. Charles County crime lab. At first, forensic experts weren’t able to get any DNA from the 20 pieces of evidence Weber sent them.

“It didn't bother me too much because I knew something eventually was going to come of this,” Weber said. “We had great evidence.”

Weber kept calling the lab through the years, asking for the evidence to be retested. It wasn't until earlier this year that she got a call back with the news she was hoping for – a partial DNA profile.

It wasn’t enough to upload to a database of criminal DNA profiles known as CODIS, but Weber didn’t mind. She thought she had her man.

She tested the partial sample against her main suspect, a man known for beating and robbing prostitutes in St. Louis back then, but it wasn’t him.

“Obviously, I was pretty disappointed in that,” she said.

Experts at the St. Charles County Crime lab kept working on the evidence, and in the Spring, they found a full DNA profile from a piece of evidence from Mihan’s crime scene.

They ran it through the national criminal database and got a hit.

Chapter 2 Learning about a killer

The DNA report was the first time Weber had ever seen the name Gary Muehlberg. It wasn't in any of the hundreds of pages of police reports written on the cases.

He was serving a life sentence for killing Kenneth “Doc” Atchison. The 57-year-old went to Muehlberg’s house in Bel-Ridge to buy a car from him in 1993 and was never seen alive again.

In that case, Muehlberg put the victim’s body in a makeshift coffin and kept it in his basement until St. Louis County police found it. It reminded Weber of the types of containers the rest of his alleged victims were found in.

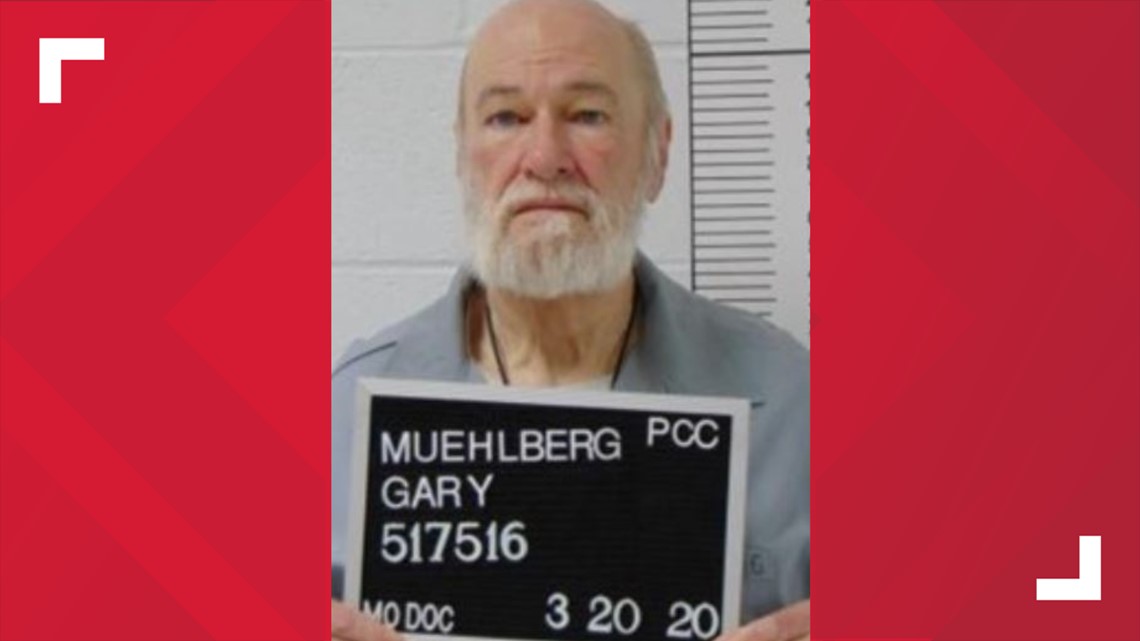

Then, Weber went to the Missouri Department of Corrections website and searched for his mugshot.

“When I pulled up his picture, I was shocked by the person I saw,” she said. “You know, he just looked like a typical grandpa. He was not the monster that I was expecting to see.”

Little’s sisters did the same thing.

“All that's going through my head when I saw it was, ‘You look so normal. You don't even look like you're in a prison. You look like you've been sitting out on somebody's deck having the grandkids play at your feet,’” Studt said. “And all I kept thinking is, ‘Why? Why would you do that?’"

Weber couldn’t wait to ask him.

“First thing I want to do is do my homework on Gary,” she said. “I started contacting people that knew Gary, interviewing them, trying to find out what kind of person he was. Everybody said he was, you know, full of himself. He thought he was better than everyone else.”

Muehlberg was one of three children - two boys and a girl. He was born in St. Louis, but the family moved to Kansas. That's where Muehlberg got married the first time and had a child.

In 1972, he went to prison for rape, kidnapping and aggravated robbery, according to the Salina Journal Sun. The victim told police Muehlberg bound and gagged her at knifepoint inside her home and asked if there was money in the house before leaving abruptly without searching for any. She had been babysitting while her parents were away, according to the newspaper.

Muehlberg’s attorneys ordered a mental exam to determine he was "insane at the time of the commission of the alleged crime,” according to the newspaper.

After prison, he went to Central Methodist University to study psychology. He went to Central Missouri State for graduate school, got married again and moved to St. Louis to be closer to his wife’s family.

The couple had two children, who are both deceased. The couple also divorced.

Armed with as much as she thought she needed, Weber went to see Muehlberg at the Potosi Correctional Center. His 6-foot-4-inch, 208-pound-frame walked through a metal door and sat across a table from her.

Weber’s heart was racing.

“I've waited 14 years to talk to this individual, so for him to sit down in front of me, I was just worried he didn't want to talk to me,” she said. “But that wasn't the case."

Weber said Mueblberg talked for her for an hour.

"He was like, 'OK. What are you here for?’ Like, 'Quit talking about what I had for lunch today. What are you here for? Let's cut to the chase,'” she said.

She told him she was there to talk about Little’s cold case.

“His main concern was the death penalty,” she said.

The second time she went to see him, she was armed with letters from prosecutors in St. Charles, St. Louis and Lincoln counties. Each of them pledged not to seek the death penalty and assured his life in prison wouldn’t change – only if he gave a full confession.

“At that moment, he said, ‘OK, let's get to it,’” she recalled. “And we began talking about the murders.”

Chapter 3 The confessions

For three hours, Muehlberg gave Weber as many details as he could recall about the three murders she was there to talk to him about. He told her he brought all of his victims to his Bel-Ridge home and killed them there.

Some of them he kept on the property for months before disposing of their bodies, including Little's. He told Weber he bought the dresser he converted into Little's coffin as an undergrad.

His house was demolished about a year ago.

Former neighbor Janet Hake remembers when Muehlberg lived just two doors away from her.

“I would have no idea he was a serial killer,” she said. “I couldn't even believe that he killed the guy that he did.”

When the house came up for rent, Hake took a tour.

“In the very back, he built a concrete room, and I guess that's where he was doing his killing,” she said. “So nobody would hear it or see it or smell it.”

Muehlberg wasn’t proud of what he did and was clueless as to why, Weber recalled of their conversation.

“He said he had a great family and a great upbringing,” she said. “He has no reason as to why this occurred.”

The only time he grew emotional was when he talked about his brother's death in Vietnam, she said.

He told Weber he knew Little had a son after seeing interviews with her parents on TV.

“He wanted to know if this will help him, and I said, ‘I certainly hope so,’” she said. “And at one point, he did look down at my body camera and said, ‘I'm sorry.’”

A few days later, Weber got a letter from Muehlberg. He told her he hadn’t told her everything and outlined two more murders. Donna Reitmeyer was one of them.

Reitmeyer's nude body was found June 11, 1990, inside a rubber trash can on the sidewalk along Gasconade Street near South Broadway. Her body was too badly decomposed to determine a cause of death. She was 40 years old and left behind three adult daughters.

The identity of the last woman Muehlberg said he killed remains unknown.

“He says that he disposed of the young lady in a metal barrel with a spring-type lid on top, and he left her body in a self-serve car wash, he says, on Natural Bridge,” she said.

She couldn’t find any police reports matching that description in St. Louis City, but she tracked down the son of a carwash owner in that area who remembered his father being upset after a body was found at their other location in Pagedale.

A former Pagedale officer also told an investigator he remembered a body was found there but did not remember what happened after it was discovered.

Weber said she is now working with the St. Louis County Medical Examiner’s Office to determine whether any women’s bodies found in 1991 match the description.

Muehlberg is now in kidney failure and isn’t expected to live long enough to be sentenced for these crimes. Weber believes he still holds secrets.

“I get the impression that he's holding back for the fact that he doesn't want to be portrayed as that monster,” she said.

To Little’s sisters, that’s exactly what he is.

To watch 5 On Your Side broadcasts or reports 24/7, 5 On Your Side is always streaming on 5+. Download for free on Roku or Amazon Fire TV.