ST. LOUIS — Jean Renaud became septic just weeks after she gave birth to her first child.

“I ended up with appendicitis, and I could not nurse,” she said.

Her pediatrician recommended her newborn get breast milk for his first six months.

“My sister had a baby she was nursing, and we were able to use her milk to supplement until I could nurse again,” Renaud said.

The experience stayed with her, so when she gave birth to her next two children she joined thousands of women across the country who donate breast milk to nonprofit organizations like the Milk Bank.

Related article: Baby formula causing disease in premature babies, lawsuit argues

Attorneys now allege that donor milk can mean the difference between life and death for premature babies whose mothers may not be able to produce milk immediately following an unexpected pre-term birth or for a variety of other reasons.

Multiple studies show premature babies who are given formula made with cow’s milk are more likely to contract a deadly intestinal disease called Necrotizing Enterocolitis, or NEC for short.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates 1 in about every 10 deaths in NICUs are because of NEC. Those who survive it can be left with lifelong health complications.

The I-Team learned that babies have access to donor milk varies widely across the country.

The study titled, “U.S. state policies for Medicaid coverage of donor human milk,” found that more than half of very low birth weight babies most at risk for NEC are born in one of the 35 states that lack donor milk coverage, according to a 2022 study published in the National Library of Medicine.

In addition, researchers found no state currently covers the cost of donor human milk whether inpatient, outpatient or for all infants who may benefit from its use.

“State and federal level advocacy is needed to ensure that donor human milk is available to all infants based on medical necessity, rather than privileging infants who happen to be born in a state or district where access is guaranteed,” according to the study. “High-risk infants would particularly benefit from legislative and regulatory changes that would increase patient access to and affordability of donor human milk, including mandated coverage.”

Illinois currently offers commercial and Medicaid coverage. Missouri offers Medicaid coverage only.

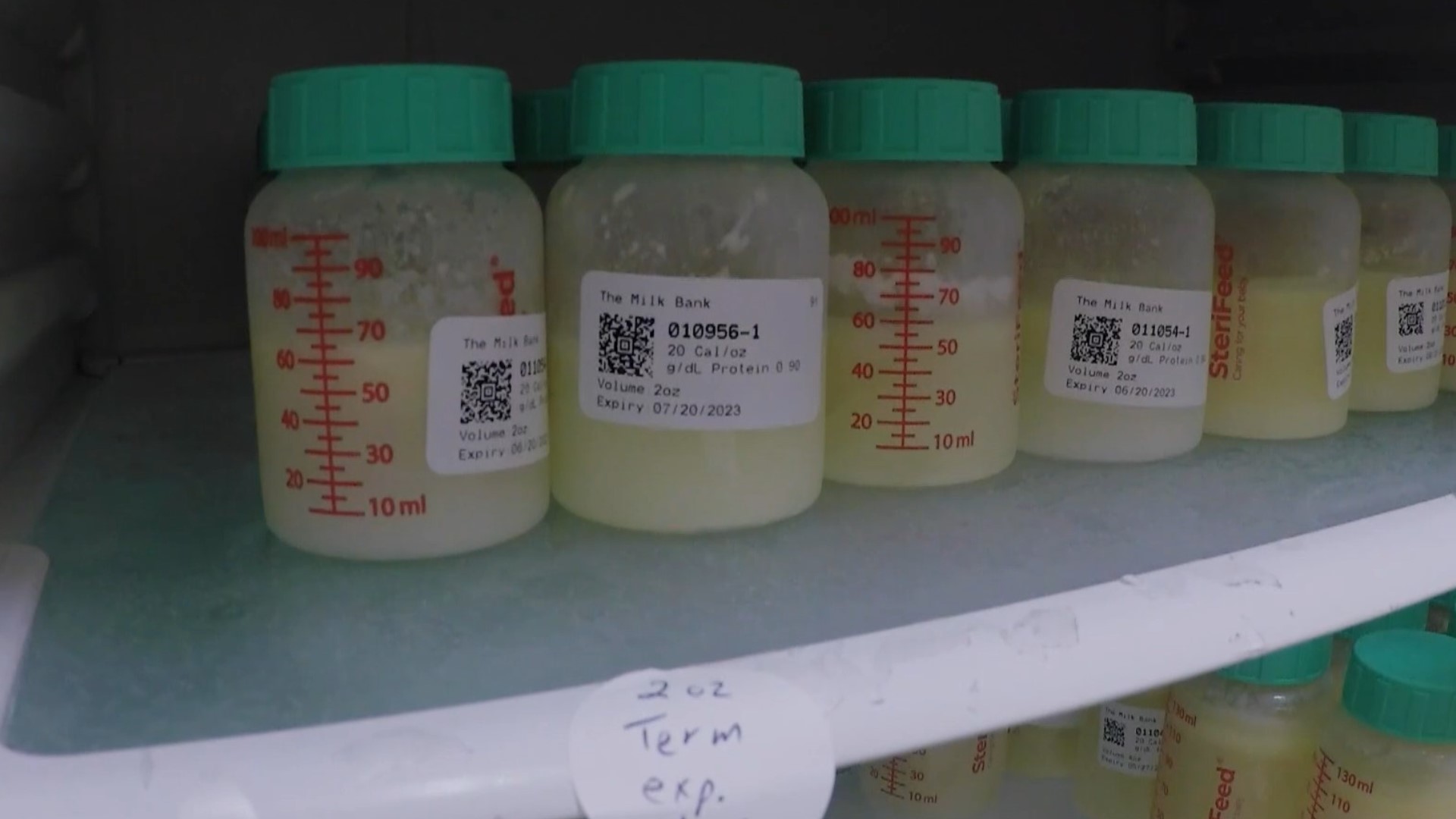

The Milk Bank and other human donor milk organizations advocate for increased coverage of donor milk, according to Mary Timmel, regional advancement coordinator for The Milk Bank.

“The studies that have been done around pasteurized donor human milk for NICU patients are pretty clear that infants fed just a human milk diet are much better, have much better health outcomes, and then when it comes to NICU patients, those health outcomes really increase exponentially,” Timmel told the I-Team.

Formula companies like Mead Johnson disagree.

On Thursday, Mead Johnson attorney Phyllis Jones told a jury there is no scientific proof that cow’s milk-based formulas cause NEC – only that human milk better protects a premature infant from it.

She said the pasteurization process donor milk goes through also reduces some of its nutritional value.

She also said neonatologists rely on cow’s milk-based formulas like their products to help premature babies grow, because breast milk – whether it’s donated or from a baby’s mother – sometimes isn’t enough.

She told jurors neonatologists often add cow’s milk products to human milk to boost the amount of nutrition it takes to grow a premature baby.

“Babies who don’t grow, don’t survive,” she repeated inside a packed courtroom at the St. Clair County courthouse in Belleville.

Attorneys for the plaintiff, a Fairview Heights mother whose baby died from NEC, told jurors they will be presenting research that shows premature babies on human milk-only diets who don’t grow as fast as their formula-fed counterparts do not suffer any long-term neurological or physical effects, despite starting smaller in life.

In this case, the premature infant died after its donor milk diet ceased when he was transferred from St. Louis Children’s Hospital to Memorial Hospital in Shiloh, where donor milk was not available.

The case is the first of hundreds filed nationwide against formula companies Mead Johnson and Abbott to make it to trial.

At issue is whether the companies did enough to warn parents about the increased risk of NEC in premature babies who are given their products.

Plaintiff’s attorney Sean Grimsley spent part of his opening statement alleging formula companies like Mead Johnson do not invest in making human-milk formulas because it wouldn’t be profitable enough.

He said formula companies often encourage hospitals to use their products by offering to give it to hospitals for free should they agree to use it in 90% of their feedings.

“That can be huge for some of these cash-strapped hospitals,” he said.

Donor milk is not free.

One study estimates the average cost of donor milk is $3 to $5 an ounce.

Premature babies who weigh 2 pounds need at least 5 ½ ounces a day, according to the Children’s Health Association. Full-term infants consume anywhere from 32 to 45 ounces a day.

It can cost hospitals that maintain their own human milk banks about $150,000 annually, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Despite the cost, Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta reports it saw a 77% decline in NEC cases when it started human milk only in its NICU.

On its website, The Milk Bank also quotes studies, which concluded, “The cost of using banked donor milk to feed premature infants is inconsequential when compared to the savings from NEC prevention,” and estimated the reduction in hospital length of stay, NEC and sepsis could save hospitals as much as $11 for each dollar spent on pasteurized human donor milk.

Timmel said so far The Milk Bank has been able to fulfill all of the requested amounts of donor milk from the hospitals it serves in Missouri, Illinois, Indiana and Kentucky. She would not say which hospitals use it.

Timmel recommends expectant parents ask the hospitals where they are planning to deliver if they have donor milk on hand should their baby be born prematurely.

Jean Renaud was one of the nonprofit’s most prolific donors, giving about 1,100 ounces of frozen milk.

“We celebrate those large donations, but for NICU patients, every ounce counts,” Timmel said.

The nonprofit doesn’t have any minimum amounts mothers need to donate.

Donors must submit bloodwork and a letter from their medical provider as well as answer a questionnaire online before their milk is accepted.

The donated milk is then pooled with the milk from other mothers at the organization’s lab in Indianapolis where it is pasteurized and tested multiple times before it is given to hospitals, Timmel said.

Renaud said she hopes donor milk will someday become available to every baby who needs it.

To learn more about how to donate to The Milk Bank, click here.

If you'd like to get in touch with our I-Team, leave a voice message at 314-444-5231, email tips@ksdk.com or use the form below. All calls and correspondence will be kept confidential.