ST. LOUIS — With the Arch in sight, plenty of space and lots of character, Travis Sheridan said he lucked out when he found this property in St. Louis’ Old North Neighborhood.

“I just fell in love with it instantly,” he said. “The mixed income, mixed race, mixed education… it’s a great sense of community.”

His biggest obstacle? Convincing a bank, any bank, to give him a loan.

“One lender, not in writing, but over the phone said, ‘Look, you know what you qualify for, just pick another neighborhood,’” Sheridan said.

In his historic neighborhood, there’s also a historic problem: mortgage lending discrimination.

“There were six banks that said no before the seventh one said yes,” Sheridan said.

A second home he bought, he had to apply to four different institutions before he finally got approved.

“That’s wrong, it hurts me. It hurts you,” said Elisabeth Risch, Assistant Director with the Metropolitan St. Louis Equal Housing and Opportunity Council. “It hurts, kind of, our whole community.”

She said redlining has historically been a barrier for fair housing, dating back to the 1930s.

“The practice was, they would identify areas of higher minority concentration and red them out on the map and then deny access to credit,” Risch said. “Because they were thought to be too risky.”

Her organization works with local non-profits to help erase those red lines that box in communities and limit their growth.

“Sixty years after the Fair Housing Act was passed… we still have this issue,” Risch said.

In the blocks around Sheridan’s home, the effects of redlining in Old North have become clearer: abandoned buildings, crumbling homes and very little new money coming in.

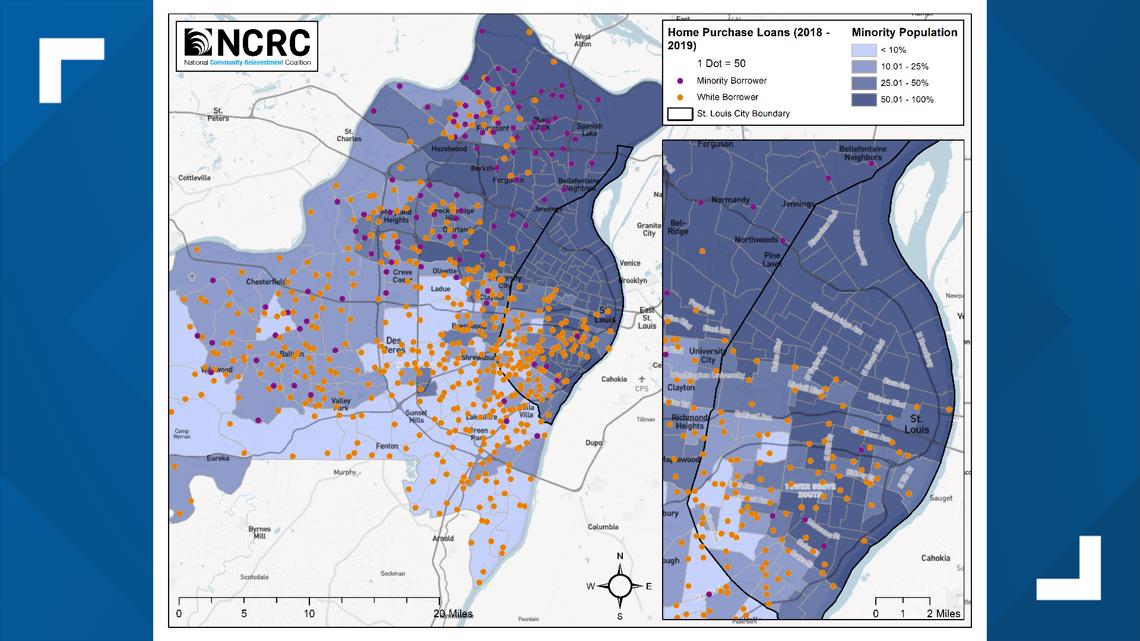

The 5 On Your Side I-Team analyzed data from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and found that between 2018 and 2020, only about 30% of home loan applications in Old North and surrounding areas were approved by banks.

The average for the entire St. Louis metropolitan area is much higher, at 56%.

“We have the largest homeownership gap between black families and white families in the country right now,” Risch said.

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 made it illegal to deny a loan just because of a borrower’s address or skin color. Despite being the law, the numbers show it’s still happening.

The St. Louis Metro is 18% black but just 5% of home loans in the past three years went to black applicants. And black families were 145% more likely to be denied a home loan than white families.

“Black families don’t have the same level of access to mortgage products as white families,” she said.

EHOC tracks lending and sent a letter to the U.S. Federal Reserve about one bank specifically – First Mid Bank and Trust.

From 2018 to 2020, less than 1% of First Mid Bank’s home loans in the St. Louis area went to black applicants.

In a statement to the I-Team, a spokesperson wrote:

“First Mid Bank & Trust strongly condemns the practice of redlining and will continue to follow all compliance regulations as we have done throughout our bank’s 156-year-history. As we enter the St. Louis market, and because we respect the diverse history of this area, we have engaged in productive dialogue with the consumer advocacy groups. We have shared with them our plans to offer assisted-down payment mortgage products that will benefit underserved communities. We are also actively exploring new ways of improving access and enhancing outreach to all potential homebuyers. We trust the resulting review process by the Federal Reserve and look forward to serving this community.”

“We were really startled by how bad their data looks, compared to all of the other banks in the region,” Risch said.

Sheridan fears if something doesn’t change, discrimination will stifle growth in the neighborhood he’s proud to call home. He fears parts of the city will never change.

“Boxing people out means that new investment isn’t coming to the neighborhood,” he said. “With new investment comes new opportunities.”