RICHMOND HEIGHTS, Mo. — On Dec. 31, 2016, Jessica Carter and her husband, Delvin, had to make a crushing decision: to save Jessica's life meant ending the life of their first, unborn daughter, just 20 weeks along at the time.

"I wouldn't wish it on my worst enemy,” said Jessica. “But out of that, I was contacted by a lot of women who went through the same thing."

Jessica is telling her story because she knows too many moms are dying in childbirth.

A woman in the US today is more likely to die in childbirth than her mother was, decades ago.

Since 1990, the rate of women dying in childbirth in the US increased faster than it did in countries like Zimbabwe and Botswana.

It’s a crisis hitting the black community the hardest, and that disparity is the greatest challenge for programs in Missouri that are trying to save black moms’ lives. African American moms are three to four times more likely to lose their lives due to pregnancy complications than white moms.

Jessica Carter says she was almost one of those women. Ja'Liyah, now eight months old, is her miracle baby.

If wasn't for a visit with a midwife at Jamaa Birth Village in Ferguson, Jessica and Ja’Liyah might not be here. The day before she lost her first baby, that midwife told her she had dangerously high blood pressure and needed to go to the emergency room.

Jessica later learned that her OB/GYN had discovered her high blood pressure weeks before, but never mentioned it

"That information is what saved my life, being aware,” says Jessica. “If I would have taken my original doctor's advice, I would have sat and just waited, and waited, and waited. I would have died."

After losing her daughter, Jessica spent five days in the hospital fighting for her own life.

What happened to Jessica happens far too often right here in Missouri. In 2015, 113 black moms died for every 100,000 births. That number is just 34 among white women. And experts estimate that there are 100 pregnancies with serious complications for every maternal death.

"I think it's unconscionable because this isn't a phenomenon that is unique to St. Louis,” said Susan Kendig, JD, WHNP-BC, FAANP, a Women’s Health Integration Specialist with SSM Health – St. Mary’s Hospital in St. Louis. “Unfortunately, Missouri is among the states with the highest disparities."

She says what maternal-fetal health experts are really trying to figure out “is where is that breakdown. And I think, again, it's listening to women's voices."

There are solutions. A national group called the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health, known as AIM, is putting a medically proven set of healthcare standards in place for the entire maternal medicine field, in states willing to adopt their guidelines.

Missouri doesn't qualify as an AIM state yet, but SSM Health St. Mary's in Richmond Heights is already following important AIM recommendations in everyday practice. The hospital is putting what AIM calls patient bundles to work on the maternity floor.

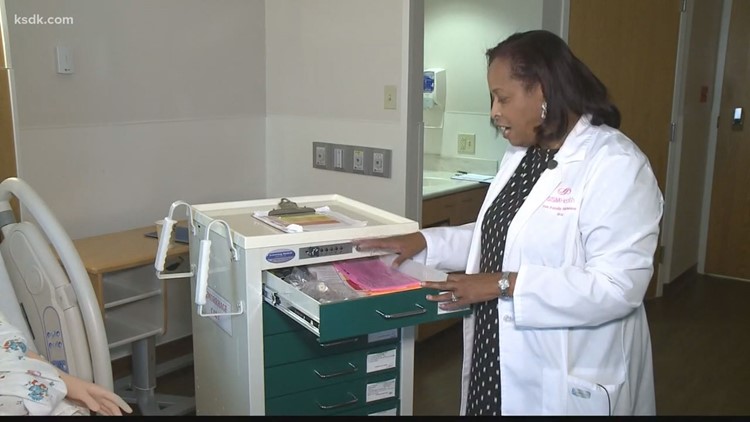

A bundle is a structured way of improving care and patient outcomes. In practice, one bundle is a cart full of supplies to prevent and stop bleeding or hemorrhage. Judy Wilson-Griffin, SSM Health St. Mary's perinatal clinical nurse specialist, gave 5 On Your Side’s Kay Quinn a tour of the hemorrhage cart.

"We have oxygen masks, we have labels, we have IV tubing blood equipment to draw blood with and we also have medication,” Wilson-Griffin said, pointing out items on the cart.

There are several of the carts on the maternity floor, their drawers bulging with critical supplies that can save a mom.

Another bundle involves patient assessment. Nurses and other maternal-fetal experts evaluate every mom who comes into the hospital for her individual risks during delivery. Then, they post the results on an electronic whiteboard for every doctor and nurse to see.

"So, if they had high risk, it's red, and if they’re medium risk, it’s yellow, and if they're low risk, it's green,” says Wilson-Griffin. "So, for example, if a mom has had four C-sections, she would be at high risk."

Amniotic fluid in the bloodstream during delivery can also kill. There’s another patient bundle that includes life-saving medicine to stop that fatal complication in its tracks.

The hospital is even training staff in new ways. They’re getting to know Victoria, a robot mom who can talk, bleed, and even have a baby.

"So, if somebody comes in with a medical crisis, the team knows exactly what to do,” says Kendig.

Ja'Liyah is the joy of her parent’s life. But Jessica still grieves the loss of her first daughter.

"It was depressing. I didn't know who I was, for a long time," says Jessica. "There was a lot of shame and regret behind her, you know, questioning if it was your body, did you speak up enough? What did you miss?”

She hopes sharing her story will motivate people in the medical community to work harder to understand women of color and understand the unique barriers that keep many of them from getting the care they need.