ST. LOUIS — For 10 years, being an EMT — or emergency medical technician — never got boring for Liz Smith.

“I think it's just the nonstop adrenaline,” Smith said. “I never got nervous or anxious. I just surprised myself that I even could do it.”

Smith put her life on the line to help others as a member of St. Louis Fire Department Bureau of Emergency Medical Services. Even as COVID-19 case numbers increased around the country, she was often the first person on the scene to help.

“One of my last ones, I delivered a baby,” she remembered. It was one of her last shifts before a mysterious illness forced her to seek medical care for herself in late February 2020.

“I just, it was more than just tired, but I wasn't breathing right. I couldn't breathe,” Smith said. “So, two days I was fighting to breathe with just no relief. Then three days after that, I went into cardiac arrest.”

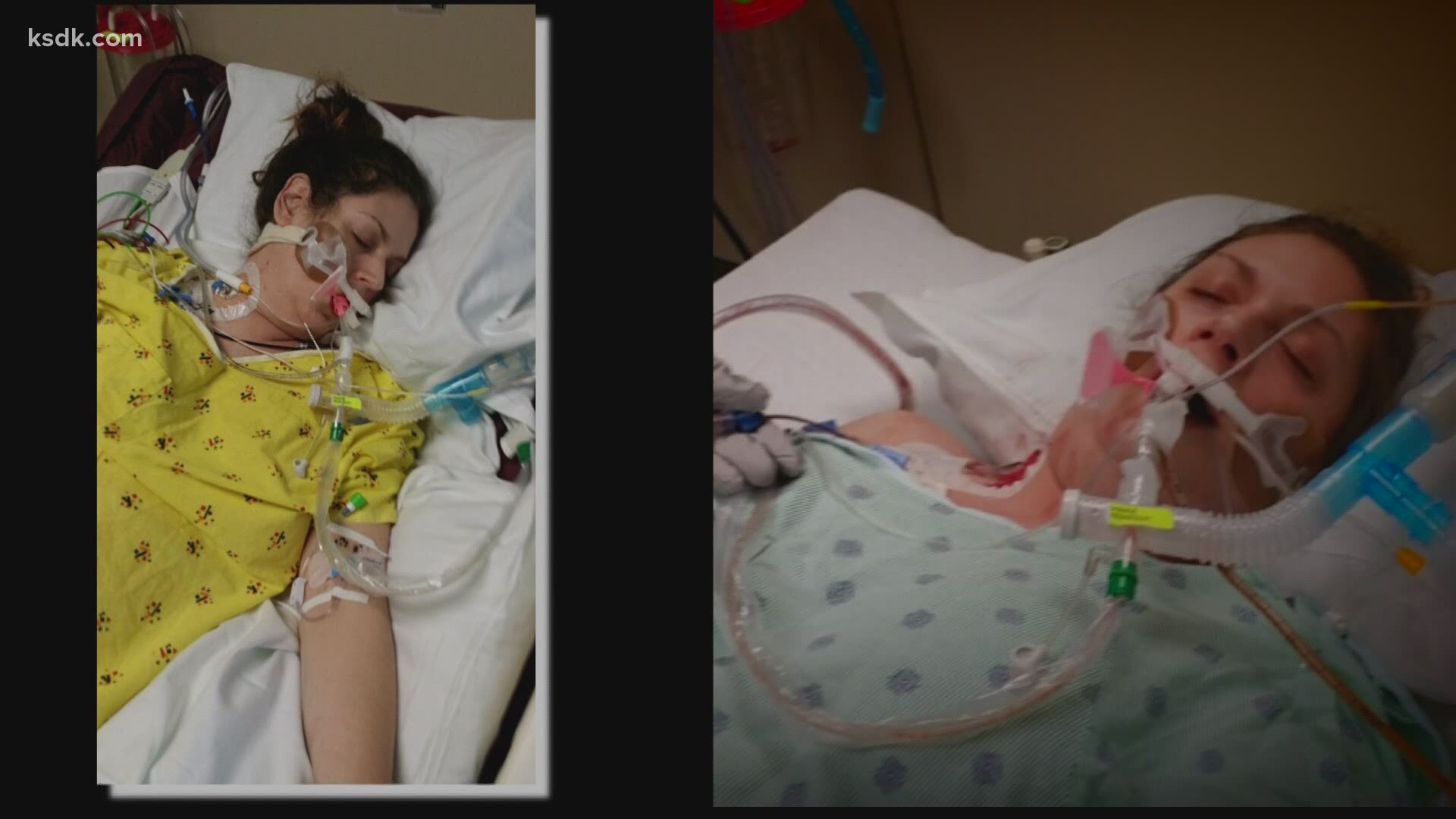

A year into a global pandemic, Smith’s experience would sound familiar for many of the 29 million Americans who have been diagnosed with COVID-19. When Smith was admitted to the hospital, tests were hard to come by. Her health declined quickly.

“I coded three times, they got me back three times and they told them there's nothing more they can do for me, call the family so they can say goodbye. You know, I wouldn't make it through the night,” she said.

Smith spent the next month in a coma and wouldn’t leave the hospital for another two months. Today, Smith is unable to return to work, and the aftermath of her illness has long-term repercussions.

“They said basically I just have a bunch of holes in my lungs, which the cavities had been formed. There were like blister-like blobs all over them as well, where there would be healthy tissue and filled with fluid,” said Smith.

Smith’s mother helped her file for workers’ compensation through the City of St. Louis. She said her claim was denied.

“Should have been really easy, but they turned around and said, 'No, she just had the flu,’” Smith said.

Scott Moore, an attorney and human resources consultant for the American Ambulance Association, explained there were concerns that first responders would have claims for COVID-19 denied because they couldn’t prove that they caught the illness from work.

“I have heard of others who have been in situations where they say, you know, we don't know this is work-related,” said Moore, who was also an EMT for almost 20 years. “Let's be serious. Most EMS people are more likely to be exposed than your average everyday worker.”

“Do I think it's fair? Absolutely not. If someone contracts an illness or is injured at work, it should be covered by workers’ compensation,” he added.

Governor Mike Parson addressed that in April 2020 by sending an emergency rule to the Department of Labor and Industrial Relations. It stated that first responders who were diagnosed with or quarantined for COVID-19 were presumed to have gotten it at work and qualify for workers’ compensation.

In 2020, the state approved $316 million in workers’ compensation benefit settlements for COVID-19 injuries and fatalities. Out of 3,806 COVID-19-related injury reports the Division of Workers’ Compensation received from St. Louis city and county, more than half were people in the health care and social assistance industries, including EMTs like Smith.

“It’s an extreme slap in the face,” said Smith’s mother, Marcia. “At some point she's not going to have COBRA anymore and she's going to have to rely on government insurance.”

When asked about why Smith’s claim was denied, a City of St. Louis spokesperson wrote, “There are no records to substantiate this claim at this time.”

Doctors are evaluating Smith for a lung transplant. She will never be able to return to work as an EMT, among other things she has to write out of her plans.

“I guess they've accepted the fact that I'll never, like, be back on the track, working on the truck. They've told me I can't have kids at all because they'll kill me. There are different options I don't have anymore,” said Smith.

“I got sick from work. I mean, that's the most probable place. There's no ifs and buts about it. That's what paramedics do. We deal with sick people. Sometimes we get sick,” she added.

Moore put it another way.

“EMS folks regularly put themselves in harm's way on behalf of taking care of people,” he said. “My hope is that at some point there's a recognition of the role that public safety folks play in the health care system in this country.”

Smith intends to appeal the outcome of her workers’ compensation claim. Her family said she is paying more than $800 a month for her own health insurance, and they expect that price to increase as well as other expenses she faces in the coming months. The family has a campaign to collect donations on Givebutter.