ST. LOUIS — A well-lit street is supposed to be a comforting sight at night. The I-Team discovered recently that those lights can also signal dangers that linger near parks, bus stops, and schools, right at eye-level for small children.

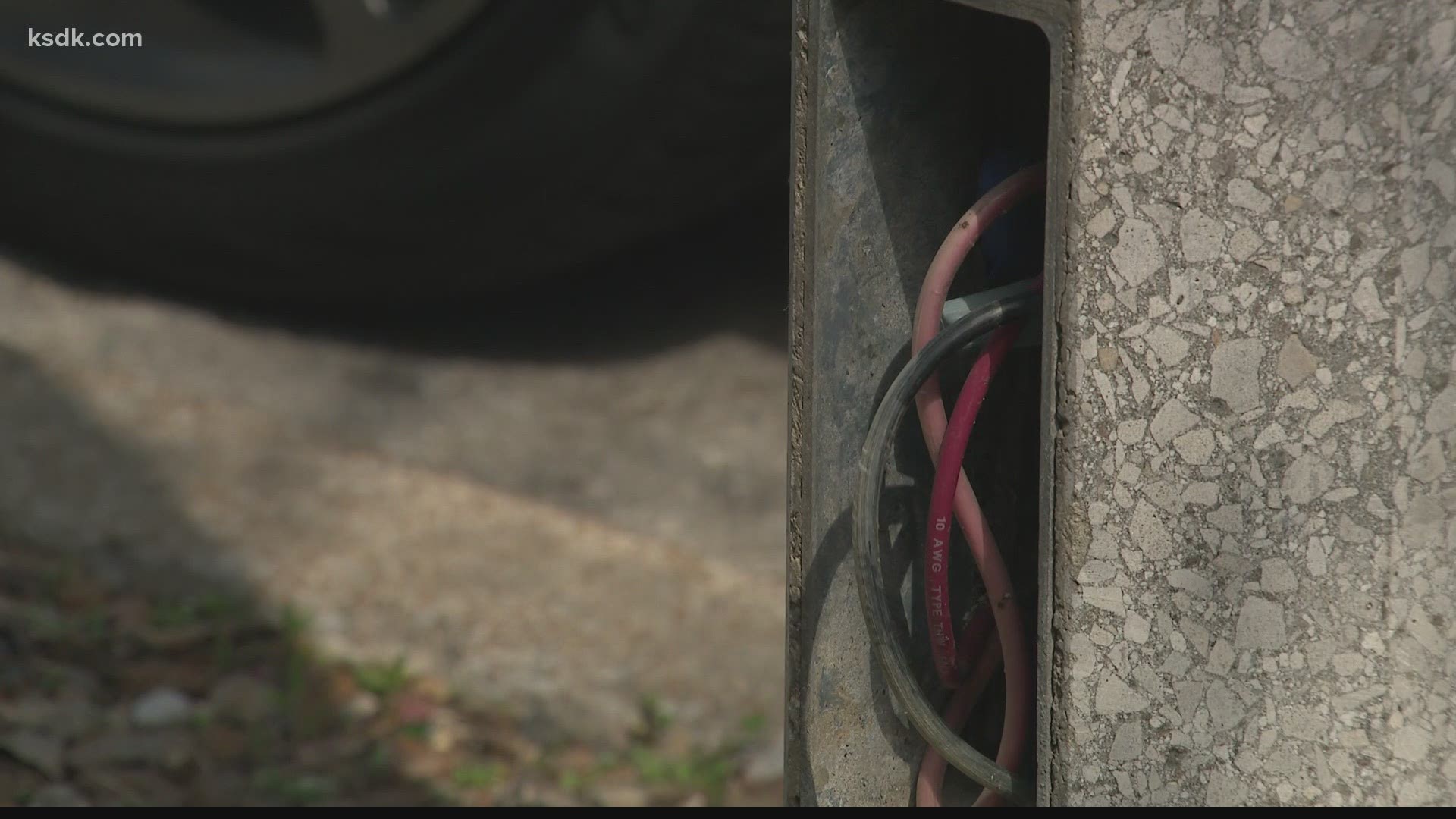

In front of Karen Kaiser’s home daycare, exposed wires spill out of a city street light’s base.

“It's very nerve-racking because I have little ones that go for walks on the regular and they're very inquisitive,” she said. “It is not safe for an adult, much less a child. If they see something like that, they want to touch it.”

Families in St. Louis have learned that the hard way. As recently as 2016, a child was rushed to emergency care after touching an exposed wire in Windsor Park.

Worse still, in 1990, a child was electrocuted by exposed wires from a city light pole.

Eric Wolff, an electrician, joined the I-Team to test the wires that are exposed on light poles all over the city.

“A kid [could] come here and play with this and touch it just right and be dead,” said Wolff about one light pole he tested, where the wires were live.

Most of the lights that Wolff tested had years-old open complaints with the Citizen Service Bureau. The first stop, a light on North Grand, has been the subject of an open CSB complaint for three years.

Neighbors reported exposed wires where lights used to be on Clara two years ago. They were still live.

“It's beeping. It's telling me, hey, there's voltage present,” said Wolff.

Margo Swinney told the I-Team’s PJ Randhawa that she worries all the time about her grandkids and other children on her street.

“It's live wiring, the way the hole is open, someone could injure themselves, possibly a child, because there's plenty of kids that get off the bus right there,” Swinney said.

The I-Team’s photographer proved the danger exists for adults too. One wrong step, and he was gouged by sharp metal coming out of a light pole.

“That's dangerous. There's no sign here. It's not coned off. There's no protection around it,” said Wolff.

Just a block away from Forest Park, on a busy Central West End street, the I-Team found street lights with missing plates and exposed wiring.

“They can brush up against that wire with their leg and given the right circumstances, could kill them,” said Wolff. “It's bound to happen if it doesn't get covered up and fixed.”

The I-Team reported a few light poles with exposed wiring the same way residents would, through the CSB. The city sent out crews the very next day and marked the requests as completed. When the I-Team returned to those light poles, they found a barrel covering live wires at one location and a few wraps of electrical tape on others.

5 On Your Side asked the city’s director of streets, Jamie Wilson, whether that was enough.

“If that's all we did, no,” said Wilson. “You put a barricade over it in order to make it safe until you can come back.”

When Wilson saw that the requests had all been marked as completed, he said, “The base plate with the tape around there should not be permanent…the final solution would be banding.”

He also made a commitment.

“I'll look at those for sure.”

Swinney said she felt that certain communities wait for permanent repairs longer than others.

“If it had been in Central West End,” she said, “it would have been corrected the same day. You know, over here in our community, really too much doesn't get fixed.”

Looking at Census data and five years of CSB reports, there are trends that support her suspicions.

Nine neighborhoods where the majority of residents are white had the fastest time to close light pole damage complaints.

It took an average of nine days to close those complaints, the CSB data shows.

In 22 city neighborhoods where the majority of residents are black, response times averaged 40 days, more than four times as long.

Wilson says location isn’t even a consideration for his crews.

“Everybody here comes to work to replace the lights. They really don't care again where it's at. We've got folks everywhere across the city. So, yeah, it doesn't bother us where it's at,” said Wilson.

The major obstacles the city faces, Wilson said, are manpower and money. One in four positions in the streets department are vacant. One light pole is knocked down each day, on average, and they cost $1,000 to replace. Meanwhile, thieves are targeting light poles to steal wiring and covers for scrap.

For the live wires covered by a barrel, Wilson said the department will need to check on funding from the “original funder.” If no funding is available, the city’s solution will be to install an underground “pull box” that contains the wires safely.

Until then, Kaiser can’t let her guard down.

“I should be able to send my kids out in the front yard and my grandson should be able to ride a scooter. And I shouldn't have to worry about this being a safety hazard for him,” she said.