INDIANAPOLIS, Indiana — The first things that Michael Johnson got when he left Missouri state prison were beef jerky, an energy drink and a Fruit Roll-Up — the things he couldn’t get behind bars.

But in prison, he got access to something he found hard to get as a student at Lindenwood University: life-saving medication to treat his HIV.

“Going from state to state made it very difficult for access to care,” Johnson said. “And I was a poor person or minority and just, you know, didn't have the funds needed to buy a car. What could've been almost a hundred dollars for just a taxi ride there.”

Johnson is adjusting to a new life in Indiana as a man open about his diagnosis and advocating for others. Monday, he spoke exclusively to the I-Team’s PJ Randhawa about being convicted with a law that legislators, prosecutors, and activists say needs to change.

Wrestling was Michael Johnson’s life. He was a standout on the mat in high school and at Lincoln College in Illinois. He joined Lindenwood University on scholarship and was part of the wrestling team in 2012.

That same year, in a routine check-up, Johnson learned that he had HIV. The openly gay student continued to date men he met on dating apps. He admits, his HIV was left largely untreated.

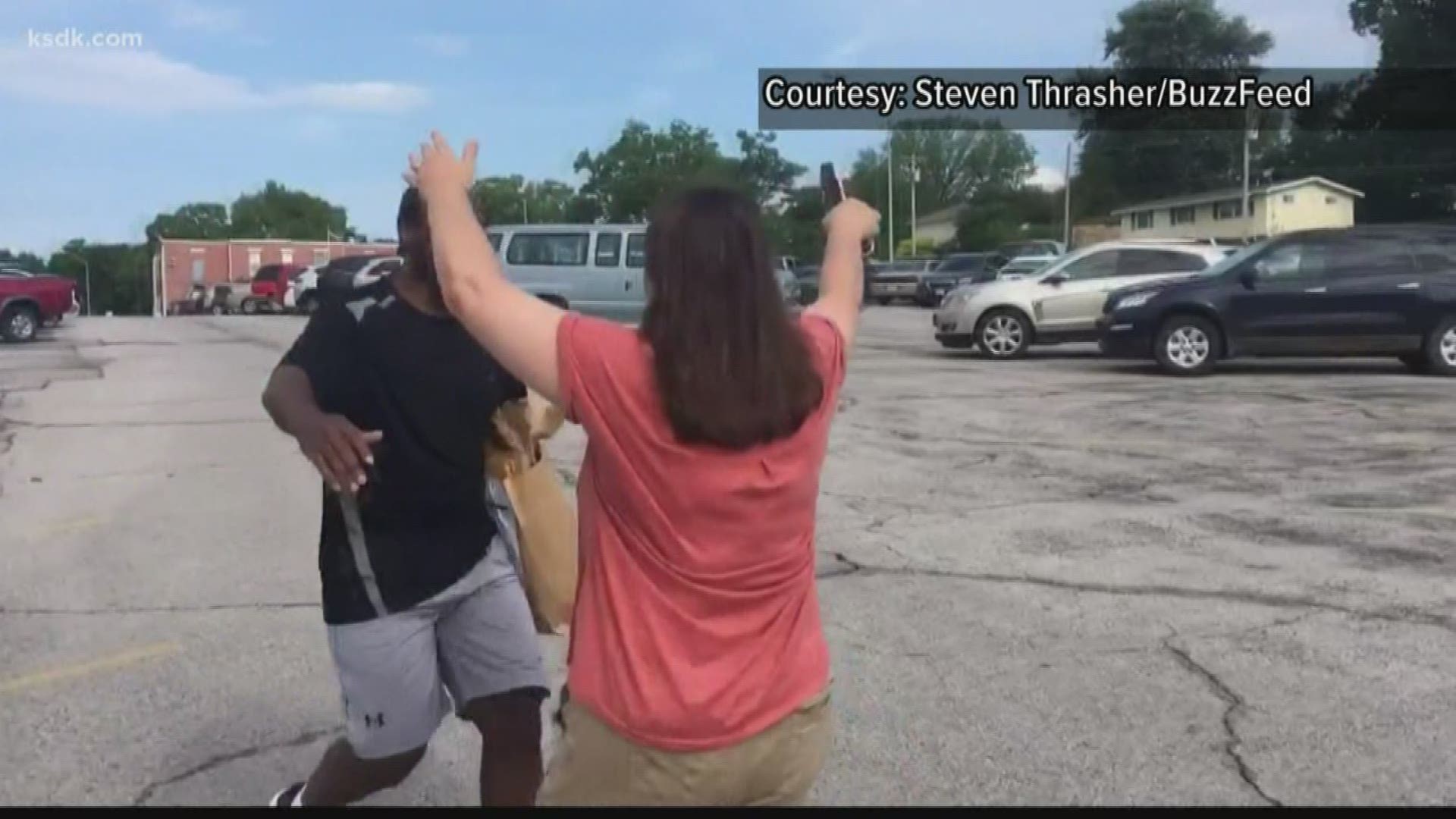

But soon after, he found himself in a legal battle over his dating life. People he dated accused him of not telling them about his diagnosis. One of his partners tested positive for HIV.

“I would never think of doing that to anyone,” Johnson said. “I do not have anything to prove that the person was lying and that I was telling the truth. And it was a he-said, he-said situation.”

Missouri and 25 other states have laws that criminalize HIV exposure. Johnson’s conviction in St. Charles County involved one of the harshest. It’s a felony to expose someone else to HIV without their knowledge, with a minimum 10-year sentence if the virus spreads to the victim.

Johnson’s charges combined resulted in a 30-year sentence starting in 2013. He was just 21 years old.

“They saw the, with a media initiative wanted to put out was that it was a scary big black gay man wrestler that was out to cause harm,” said Johnson.

In 2016, an appellate court sent Johnson’s case back to a retrial, finding that he didn’t get a fair defense. On his second time around, Johnson accepted a plea deal for a 10-year sentence. Today, he’s out on parole.

“I didn’t want to take it,” he recalled. “Under those laws it felt that they could’ve given me anything that they wanted.”

State Representative Tracy McCreery, a democrat that represents Missouri District 88, thinks this shouldn’t happen again. She is one of two Missouri lawmakers working to change the HIV transmission law that put Johnson behind bars.

“It's unbelievable,” she said. “A lot of the laws reflect our ignorance of the disease. In Missouri law, the only disease that is called out specifically is HIV. Just because of that there's a lot of stigma.”

In the most recent legislative session, McCreery proposed a bill that would have changed the law to reduce the penalties and requires that the virus must have been transmitted intentionally. It didn’t pass this session, but McCreery plans to refile next year.

Missouri’s current HIV transmission law was written in the 1980s. The public understanding of HIV at the time was completely different.

Dr. Rachel Presti, an infectious disease specialist at Washington University, said there have been enormous changes from then until now.

“A lot of people were dying and there was a lot of fear from that because we didn’t know how people were getting it and we didn’t know how infectious it was,” she said.

But treatment today can make HIV almost undetectable and untransmittable.

“You can take a single tablet one pill once a day, suppress the virus, normal life expectancy, no transmission, in fact quite often we tell people it's easier to treat HIV than it is to treat diabetes or hypertension at this point,” she said.

Still, she adds laws like Missouri’s can deter people from getting tested at all.

And the St. Charles County prosecutor who put Johnson behind bars also sees problems with the law.

“I think we have an opportunity to take a look at those laws and understand how they are outdated and antiquated. I think it's time for a change,” said Tim Lohmar.

Johnson provided us with a statement from former Missouri Secretary of State and long-time supporter Jason Kandor.

"One of my last acts as Secretary of State in Missouri was to seek clemency for Michael Johnson," said Kandor. "Although we were unsuccessful in those efforts Michael Johnson's case has shed light on issues that all Missourians should be aware of. It is my hope the legislature would work with community leaders to modernize our laws to reflect science."

Johnson plans to go back to school to finish his degree and become a wrestling coach. He says that his mission is to use his story to help repeal HIV transmission laws, not just in Missouri, but also around the country.

“I want as many people as possible to know, you know, I am HIV positive, you know, so if I break down those walls so people are not afraid to speak their truth and to get their story out, there'll be the better it will be for change to happen.”