ST. LOUIS — The Mississippi River is a familiar place for many Missourians, but there’s a seldom-told history that lies just beneath the surface.

The Black Freedom School used to float along the water in the 1800s.

“John Berry Meachum and Mary Meachum were pivotal to St. Louis,” Cicely Hunter, a public historian with the African American History Initiative of the Missouri Historical Society, told 5 On Your Side.

Two names often overlooked in Midwest and American History, the Meachums were a formerly enslaved Black married couple that moved to St. Louis in 1815.

Hunter said John Berry Meachum became active in the Black St. Louis community soon after moving to the city.

“He started teaching Black folks – both enslaved and free – by 1822. By 1825, he was ordained. Then in 1827, that’s when the first African Baptist Church was erected. It was essentially serving as a church for both free and enslaved people. But it also served as a school beneath the basement,” she said.

When Missouri outlawed the education of all Black and mixed-raced people in 1847, the Meachums had to find a way to keep the lessons going without breaking the law.

“From down in the basement, they took their education and brought it here to the riverfront,” Hunter said.

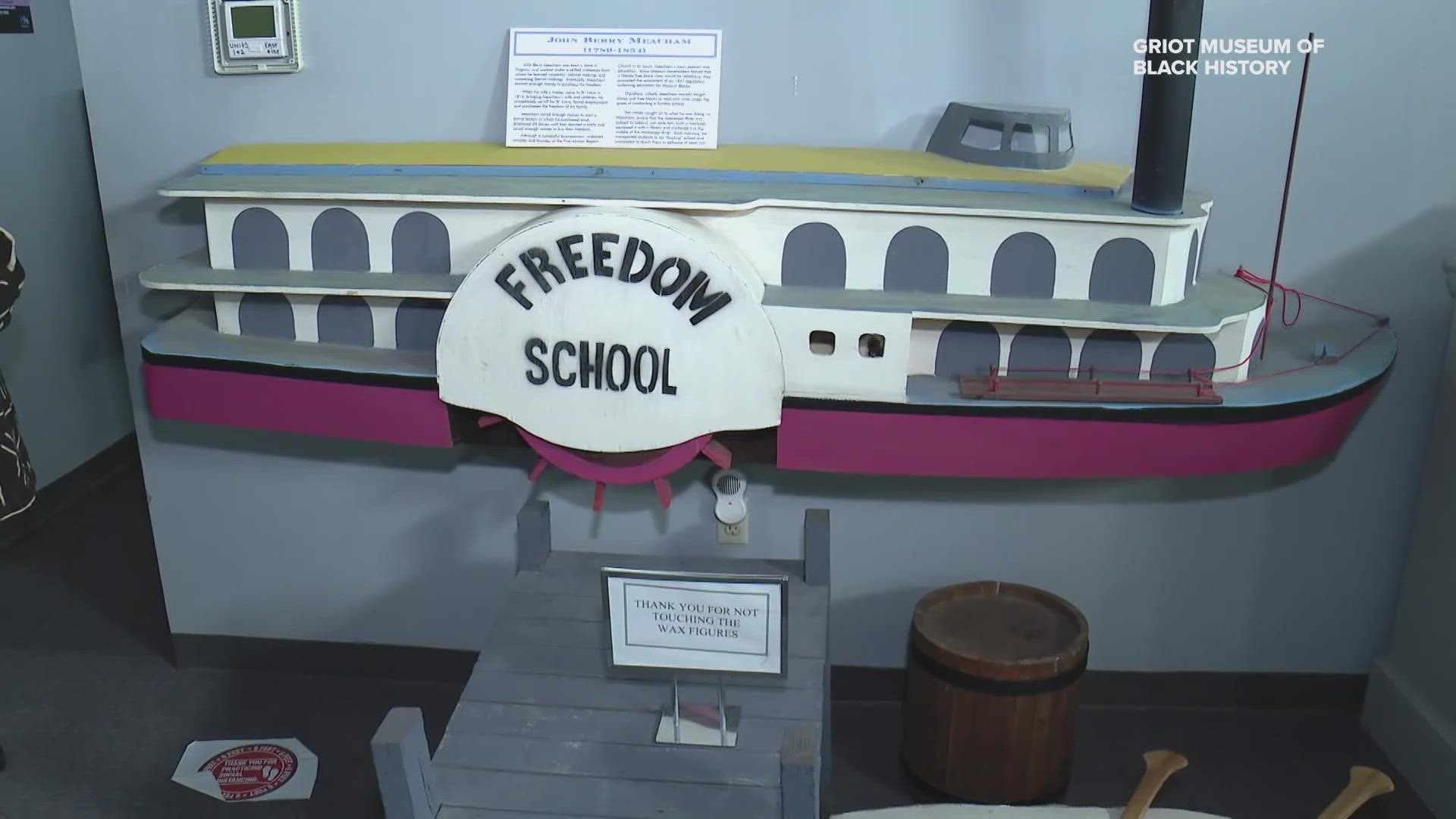

John Berry Meachum and his followers created a “floating school” – also called the “Freedom School” – on a steamboat anchored in the Mississippi River.

“They would dock along the Mississippi River, and he would bring them out to do their studying and that’s when they would come back,” she said.

The Mississippi River was federally regulated and outside of Missouri jurisdiction, becoming a source of freedom for Black people in more ways than one.

“It’s a story of Black liberation. It’s a story of freedom sought through education. It’s a story about using what’s within your means – natural resources of the land – to seek what so many people thought was rightfully theirs and it is,” she said. “Black people were self-emancipating by using the riverfront and traveling up and down the Mississippi to other places.”

After John Berry Meachum’s death, Mary Meachum became known for her role as a conductor in the Underground Railroad.

One mission in 1855 made headlines.

“Mary Meachum plotted with some other people at her home,” Hunter said. “Their essential escape was to go to Alton, Illinois, but they were actually found out.”

“Five people were arrested on that particular day. Mary Meachum… [was] also arrested a few days later. The deposition though was torn out of the book, so we don’t necessarily know what happened after. But we do know Mary Meachum was arrested and she was let go a few days later,” she said.

Hunter has spent years working to fill in the gaps that exist in Black history archives.

“There have been records that have either been destroyed for whatever reason or not accounted for because at that time Black life was not valued. But, of course, we push against that today,” she said.

She continues her work to ensure St. Louisans know about the history that exists just around the riverbend.

“There are many stories here in St. Louis. That’s just one,” she said. “But there are many stories that we need to continue to keep on our lips and on our minds so we can grow and collectively organize and continue the work that needs to be done.”