ST. LOUIS — Places like New York, Houston, Baltimore and Tucson, Arizona are bringing mental health workers into the fold when it comes to answering 911 calls – and now, so is St. Louis.

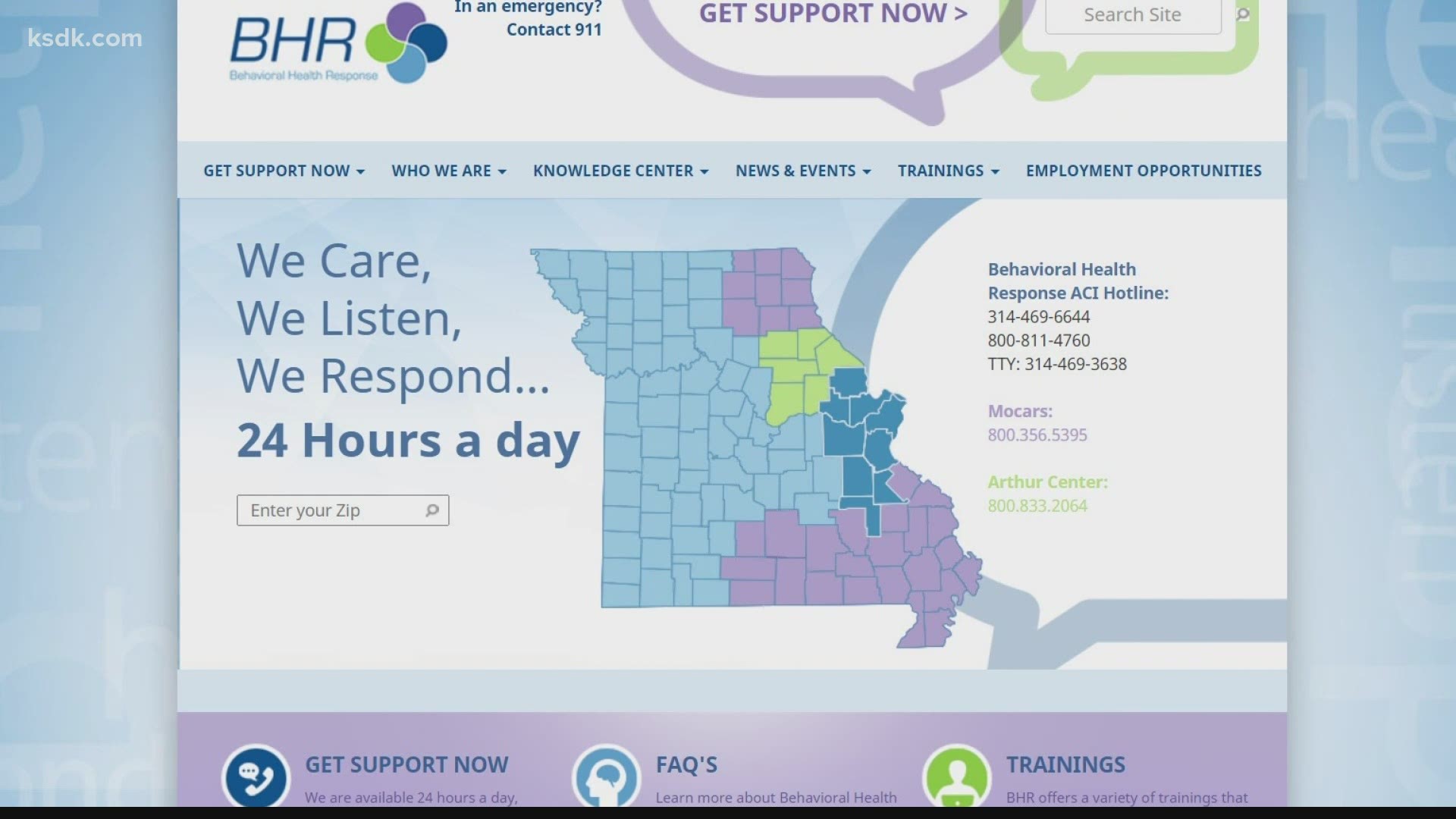

This month, the Board of Estimate and Apportionment approved a contract with Behavioral Health Response to divert some 911 calls to crisis intervention experts instead of dispatching emergency responders. The program, known as the 911 Diversion and Co-Responder Program will also pair mental health workers with police responding to crisis situations on the streets.

Tiffany Lacy Clark heads up Behavioral Health Response, the agency the city is contracting with to run the program.

“We are kind of like air traffic control, when people call us they’re in a crisis,” she said. “We talk to them, we de-escalate the situation and then we connect them to longer-term support for their needs.”

Launching the program in a city like St. Louis now is a step in the right direction when it comes to improving police and community relations, Lacy Clark said.

“We know that police officers and the justice system have become the pseudo mental health treatment plan,” she said. “This gives us an opportunity to move treatment back to treatment and let the criminal justice system focus on what they are trying to do.”

Mayor Lyda Krewson moved about $860,000 out of the jail budget in June for the program.

She said there are about 700,000 calls to 911 a year. Her office estimates the diversion program will now handle about 5,000 of those calls. But dispatchers may still send an officer if they determine there is a risk to public safety, she said.

“The 911 dispatchers will be extensively trained to determine who goes there, and, in some cases, a police officer may go also,” she said. “It's really to get people what they need versus a police car or a fire truck or an ambulance to get people what they need so that they can get through that moment of crisis and move on to a more stable situation with the help that they need.”

Krewson’s Director of Children, Youth and Families, Wilford Pickney, helped create the program. He’s also a former New York City police officer.

“Everybody wants to see cops riding around in their neighborhood right?” he said. “Well, if they're taking time to deal with these types of situations, then that's less time, they can be riding around all walking around.”

Pickney oversaw two pilot programs that took place in St. Louis in 2019.

He didn’t have any data available yet to share about the outcomes.

The model the Board of Alderman approved will put the program under the guidance of the city’s health department.

Lacy Clark said other cities are seeing positive results, and she believes St. Louis’ model will be even better because the mental health workers will be embedded with police officers.

Krewson said she expects the program to be fully up and running by the start of 2021.

Lacy Clark said she’s hiring.

And, lived experience is preferred.

“What better people to be able to help, call, respond and shepherd people that are in the midst of crisis, than people that have experienced something similar?” she asked.

For more information, visit http://bhrstl.org/ or call 314-469-4908.

Editor's note: An earlier version of this story contained in inaccurate description of the vote the Board of Estimate and Apportionment made.