Searching for Solutions: How Detroit can be a guide to get St. Louis back on track

With hundreds of millions of dollars coming to St. Louis, what opportunities have worked in other cities that could work in St. Louis?

Few American cities understand the struggles of St. Louis better than Detroit.

The Motor City reached its heyday in the 1950s and 1960s as the post-World War II industrial economy roared to new heights, bringing middle-class jobs and wages along with it.

The decades that followed brought crime and corruption, decline and despair.

That iconic city that got America where we were going eventually broke down, went bankrupt and, much like St. Louis, needed more than a minor tune-up.

Some say the Rams settlement could offer the funding the region needs to make a comeback similar to Detroit.

5 On Your Side is committing as a news organization to finding solutions. We are committed to searching for ideas to turn our region around, and we are starting in Detroit.

Chapter 1 Economic lessons in Detroit

The city’s economic engine needed a total rebuild.

“Detroit was broke,” said journalist and author John Gallagher. “When I got here in 1987, working for the Detroit Free Press. The city was still on its long ... decline.”

Gallagher studied urban development in shrinking cities for more than three decades. He said when the American auto industry sputtered and stalled, the Motor City was dragged down with it.

“Detroit hit rock bottom. And that’s when you lose two-thirds of the population and 90% of the jobs. And you have 100,000 vacant lots in the city because homes have been abandoned and burned out,” he said. “You are rock bottom.”

There was nowhere else to go but up.

“I picked the right time to become mayor, there’s no doubt about that," Mike Duggan chuckled after a Feb. 1 press conference.

Mayor Duggan's office recently touted a new achievement for the city’s unemployment rate, which dropped to 6.8% in November 2022. The height of the city's unemployment reached 38% in 2020 during the worst stretch of the pandemic. The new milestone marks the first time in 22 years that the jobless rate in the city limits fell below 7%.

Monthly jobs reports from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show the city and the surrounding metropolitan region began a slow, steady economic recovery after the precipitous drop-off during the decline of the automotive industry. After losing more than 334,000 jobs between the fall of 2005 and the spring of 2011, the Detroit region gained all of those lost jobs back and then some, adding more than 383,000 jobs before the pandemic hit. Despite that more recent setback, the resilient city has nearly recovered all of the jobs it lost during the coronavirus.

Everywhere we went in Detroit, people were buzzing about the city's revival.

"What Detroit been through? Shoot," Big Keith the barber said. "The city is definitely getting back after everything it's been through."

He said he recently moved back to his hometown after moving away when times get tough decades ago.

Kaytea Moreno Elst, who runs a block club in her community, noticed a similar trend all over the city.

"More people moving in," she said. "You're seeing people born and raised here go to Texas or New York ... they're coming back."

"I think other cities had stuff to teach Detroit," Gallagher said. "I think Detroit has a lot to teach other cities."

One location stands above the rest as a symbol of revitalization on the city's skyline: Detroit's famous Michigan Central train station shuttered decades ago.

After the last train left the station, the massive building fell into ruin and disrepair. Graffiti covered the premises and attracted photographers hoping to capture images of urban decay.

The iconic building will soon shed its banner of blight and become the epicenter of a new wave of transportation technology. The site's CEO, Josh Sirefman, walked the premises to tease a grand reveal in the near future.

"This all exists because of an incredible investment from Ford," he told us.

The site will feature testing spaces for self-driving cars, and other innovative technologies around e-bikes, e-scooters, electric vehicle charging stations, and drones that promise to deliver packages in remote, hard-to-reach areas.

Sirefman projects the site itself will bring thousands of new jobs to the city, and the economic activity around the area will generate thousands of other indirect job opportunities.

"The interest we see in the market is incredible," he said. “I think there’s a real recognition that mobility is something that requires everybody to really apply new solutions into the real world."

While Ford and other large corporations hope to see return on their investments in the city, other smaller businesses are benefiting from a menu of workforce training and grant programs flowing through the mayor's office.

Just a few blocks away from Michigan Central, a new startup enjoys support from Motor City Match, a grant program with backing from the Ford Foundation, JPMorgan Chase & Co., the Knight Foundation, The Kresge Foundation, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation -- all nonprofit arms of some of the oldest corporate mainstays in the area.

Tanya Saldivar-Ali, who runs Detroit Future Ops with her husband Louis Ali, gave us a tour of an old home in Detroit's Mexicantown neighborhood. They plan to convert the Queen Anne-style house in into a design-build green hub.

“This hub will actually be an incubator,” Saldivar-Ali said.

She and her husband won a $65,000 Motor City Match grant to complete construction on their workforce development center, where they intend to help contractors learn the business side of building things.

“That will push us across the finish line,” she said after pandemic-induced inflation derailed their construction project and delayed their launch.

Ford, Kellogg, Chase and their foundations all kicked in grant funds distributed through a program called Motor City Match, which operates with joint funding from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. City hall launched the program in 2015 to help businesses put down roots in Detroit.

Some of the other grants were awarded to a community grocer, a fabrics and upholstery shop, a youth start-up and entrepreneurial education center, and an assisted living center for low-income elderly adults.

A recent audit scrutinized the grant program and questioned how effective the investments really were. Duggan's office was undeterred by the criticism, and argued the grant funds often went to businesses that were still in their infancy.

"We now have 216 Motor City Match businesses open that would not have been open," Duggan told a crowd of local media and business owners. Statistics from his office claim the program has provided $11.4 million in cash grants, leveraging a total investment of $61.6 million in local companies. More than four in five of those companies are minority-owned, and nearly three in four are women-owned.

While fiscal watchdogs will continue to monitor and measure the impact of the program on paper, the business owners on the receiving end of the grant funds say the cash infusion sends a larger message to the startup community about their role in the city's resurgence.

"It’s exciting, but it’s also shocking,” Saldivar-Ali said. “Growing up here all of our lives, I'm 47, and to see this kind of comeback? This is the first time in my lifetime. Older generations have seen Detroit in it's glory, but for me, it’s the first time we’re ever seeing it.”

A similar grant went to the owners of The Red Hook, a coffee shop that offers high-speed internet alongside pastries and craft lattes.

“It’s hard to start a small business in any city,” owner Sandi Heaselgrave said. “As a first-time small business owner, banks were really hesitant to give us a sizeable loan.”

The $45,000 grant helped them expedite the launch of another location. She recently reopened the doors of her coffeeshop in a riverfront store and plans to expand into another site in the weeks ahead.

“It means we can open in two months instead of a year,” Heaselgrave said.

Aides to Mayor Duggan acknowledge that writing grants for small businesses isn't exactly revolutionary. Neither are the workforce training or education scholarship programs championed by their staff. But constant effort to bring corporate partners to the table, collaboration with nonprofits, and public outreach to people in need, slowly started capturing people's attention and shifting the narrative around the city's decline.

"Bottom line: results," Deputy Mayor Todd Bettison said.

He said other cities should take note of Detroit's incremental approach and take care to pick up small wins wherever they can find them, because sooner or later, they start to stack up into an undeniable mosaic of momentum.

"City government should do what city government does, and do it well," he said. "And then the business community will come in and they will do what they do well."

"As an investor, I'm not going to move my company, or I'm not going to invest in a place that looks like it has no future," Bettison said. "Detroit has a future. It's bright, and we're chipping away, chipping away, chipping away, and collectively working together; and St. Louis can do the same thing. It's about really coming together, it's showing those wins. And so you can't do everything all at once. It's impossible."

Bettison said they deployed American Rescue Plan funds to expand programs that already showed promise, including direct payments to people who showed up to do the work.

The city is using American Rescue Plan funds to pay high school dropouts $200 weekly 'Learn to Earn' scholarships to finish their high school diploma.

Duggan tapped 18 local nonprofits to reach out and recruit long-term unemployed workers to learn new skills. The 'Jump Start Detroit' program offers to pay workers up to $300 a month to get job training and helps connect them with area employers looking for workers.

John Cromer heads TMI Detroit, one of the nonprofits working with troubled youth. He mentors Los Rell, a local musician, who produced a jingle to give the Jump Start program some extra publicity.

"The employment rate has dropped under 7% recently," Los Rell said. "Just the whole spirit. You can just feel it.”

Cromer said when Mayor Duggan heard the catchy tune about the workforce training program, he sent a copy to President Biden. The White House recently promoted the JumpStart program as a model for other cities to follow.

“We’re an example of what’s possible," Cromer said.

Later this year, Detroit expects to add 1,200 jobs at an Amazon distribution center at the former state fairgrounds. Additionally, a new employment center will soon break ground, providing an additional 400 new jobs.

Chapter 2 Detroit's crime plan paves progress

Catching Crime on Camera

Sworn officers and civilian analysts working at the Detroit Police Department have made significant progress, rapidly closing the gap in their pursuit to identify and arrest people committing crimes.

Live video feeds from cameras installed in highly visible locations all over the Motor City stream high-definition images into a real-time crime center at police headquarters. While surveillance video is hardly revolutionary, the way Detroit markets the program has caught on with companies and consumers alike.

Police Chief James White said officers were taking reports on carbon-copy notepads when he was first sworn in during the mid-1990s.

“The criminals are getting smarter, so we have to be smarter," White said. "Technology is here. You can’t run from it.”

His officers hope their suspects can't escape it either.

“It feels good to catch the bad guy," Assistant Chief David LeValley said.

They've been doing a lot more of that these days because of Project Green Light, a public-private partnership that prioritizes safety and swift police responses around businesses that invest in the camera equipment and internet router.

“We had a lot of carjackings that were occurring at gas stations in the city,” LeValley said.

The city started small in 2016 and arranged for eight gas stations to purchase camera equipment and bright green lights that flashed outside of their stores. The gear belongs to the business, but the video feeds directly to police.

Eight years later, a map of the city of Detroit shows green light cameras have been installed virtually everywhere.

“You look for those (green lights) when you’re going to specific places to stop if they have it," Kaytea Moreno Elst said. "Absolutely, they're safer."

The mayor's office says 866 businesses have invested in the equipment since its inception in 2016. Five years later, the police reported a 44% reduction in carjackings. They attributed the progress to Project Green Light.

The color flashes a warm, inviting signal to customers, and a warning to would-be criminals. Not only are they more likely to get caught, but they're also less likely to fight charges and accept a plea deal, according to the chief.

“Oh my God, I mean it’s a game-changer," the chief said.

For a total price tag of roughly $11 million, the city installed a Real-Time Crime Center where analysts review precision surveillance network to rapidly track suspects in criminal acts. Separate software programs monitor alerts from sensitive sound receptors that feed into the ShotSpotter system.

Captain Matthew Fulgenzi showed us video of one woman police arrested within minutes after she fired off a gunshot outside a gas station.

"In this particular case, we had no 911 call, so without ShotSpotter technology, the police would’ve never been alerted to this location," Fulgenzi said.

Other hidden cameras set up around the city can detect motion or scan license plates. The images flash across a massive video wall in a control room where detectives, dispatchers, and analysts work to crack down on illegal dumping or follow suspects' movements.

“The areas are a lot cleaner, so we’ve got the convictions, we’ve got the arrests, we’ve got less dumping occurring in these areas," LeValley said.

Second Chances

As the city expedites the swift delivery of justice and its consequences, a team of lawyers is writing its redemption story one person at a time from city hall.

“We believe in second chances,” said Shayla McElroy, the community outreach manager at Project Clean Slate. “When you have misdemeanors or felonies on your record, you come across a host of barriers. Specifically, as it comes to employment, housing and educational opportunities.”

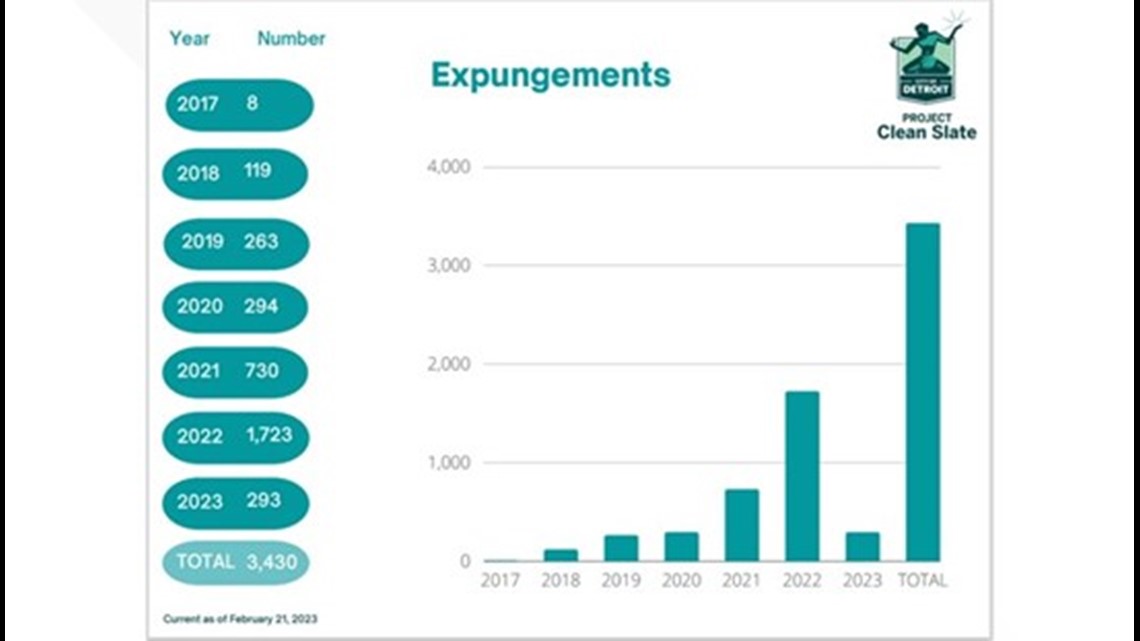

Pointing to academic research that shows ex-cons often experience lost wages and a higher risk of repeat offenses, Mayor Mike Duggan's office opened a small office in the city's legal department back in 2016 to start processing expungement applications for former felony convicts who live in the city.

McElroy had just moved back home to Detroit after working in a California jail where she saw the same people coming back to jail as repeat offenders.

“Over and over again. Sometimes, like within a 24-hour time period," she recounted. "And a lot of times, my question was, 'What’s going on? Why do you keep coming back?' And they’re like, 'It’s harder outside than it is in here.'”

Hiring a private attorney to fill out the papers, process fingerprinting with the Michigan State Police and to apply for expungement can cost up to $3,000. The cost barriers are so high, a recent study from the University of Michigan showed only 6.5% of convicted felons pursue expungement within the first five years of their eligibility. Those that do complete the process see an immediate uptick in earning potential. Research shows the average former convict with a felony sees a 22% jump in wages in the first year after expungement.

McElroy refuted any argument that giving someone a clean slate meant the policy was going "soft on crime."

“It’s not soft on crime to set somebody up for success, so they don’t have to return back to a life of crime," she said.

U of M researchers published the first-of-its-kind study examining expungement and recidivism data and found just 2.6% of the people who received an expungement went on to commit a violent crime afterward. Those rates of recidivism are lower than the rates of the population of Michigan as a whole, according to the study.

Demand for a fresh start in Detroit is growing faster than they can manage.

A city budget that started out very small has grown into nearly $1 million per year, bolstered by hundreds of thousands of dollars in grant funds from the U.S. Department of Justice and charities like The Ballmer Group.

"The first year we had this program going, we got eight expungements," Executive Director Stephani LaBelle said. "Over the years, we’ve really expanded and grown exponentially since 2019."

Last year, they processed 1,723 expungements, and have thousands more applications coming through the pipeline.

For Nick DuBose, expungement came just in time.

“After I got my record clean, the sky’s the limit,” he said with a smile. “I can do anything.”

But for years, DuBose ran into obstacle after obstacle, both in his professional and personal life. He felt that pang of guilt on a trip to Niagara Falls.

“My daughter points across and she’s like ‘Oh Daddy, what’s over there?’ And I was like, ‘Oh, that’s the Canada side.’ And I’m like ‘We’ll go there one day.’”

Except that was a promise he couldn’t keep. Two non-violent felony convictions meant he couldn't cross into Canada.

“Immediately when I said it, I’m just like, ‘Oh…’” he said.

One month after his expungement, an unexpected tragedy struck his family. His 2-year-old nephew suddenly needed a place to live, and very nearly became a ward of the state.

“He literally had no other option," DuBose said. "It was my house or the state.”

Had that felony still been on his record, his family wouldn't be whole today.

"He's living with me now, and so they squared that away," he said. "They vet you for that, though. If I got a felony on my record, my nephew goes to the state.”

DuBose provides for his family at a higher level, too. His clean record unlocked job opportunities he was previously denied. He eventually opened his own trucking company and hauls freight for clients in Michigan and Canada.

“I keep on bumping into these areas that it was just like, 'Oh, I've just never had this available for me before. Clean Slate did that,'” he said.

When it occurred to him that the same government that once branded him a felon had built him a bridge back to a brighter, safer, more rewarding future, he says the emotions were overwhelming.

"When I thought about that, that meant that I had my mayor, his team, Project Clean Slate and the team of lawyers, the Detroit Police that was doing the fingerprinting and all of that stuff, my governor's office, all working with a common goal of this for me.

“There has never been a point in my life where I had that type of team working for me,” he said. “When you think about stuff like that, it really hits you. It’s humbling.”

Chapter 3 Detroit becomes Demo City

Vacant homes were once one of the largest obstacles that stood between Detroit and a safer city. Tens of thousands of empty houses invited danger around nearly every corner.

Deputy Mayor Todd Bettison carries around a folded-up piece of paper in his pocket as a reminder of all the blight.

"Let me show you something real quick," Bettison said, unfolding the document covered in red ink.

"If you look at this map right here, you can zoom in," he told our cameraman. "This just shows you in a glance the number of abandoned houses or abandoned structures that were a real eyesore and creating blight in the city of Detroit."

In an hour-long interview, Bettison rattled off a long list of issues plaguing Detroit. Many of those problems are the same troubles we see in St. Louis.

"Abandoned houses," he said. "We had roughly 80,000-some abandoned houses in the city of Detroit at the time. They complained about garbage pickup. It was just so much."

You can still find boarded-up windows, crumbling rooftops, and graffiti-covered brick walls in portions of the city. But these days, you're more likely to see construction workers and excavators knocking down the old buildings as the city has rapidly accelerated the process of tearing them down.

“This is the nation’s largest demolition program," contractor Brian McKinney told us outside of an active worksite last month.

All that demolition creates jobs, and the city has steered most of that work to local companies.

"The city of Detroit was able to create economic opportunity for its residents, which then created more upward social mobility for the people who actually work at these companies, and that's been a very transformative thing that I think will pay dividends long after the blight is gone," McKinney said.

His company is one of several to experience exponential year-over-year growth in business. He moved back home to Detroit for the opportunity to invest in his hometown.

“Whenever you have these structures, you can have dangerous crime," he explained. "The city has really done a great job of making sure removing blight is also a way to make the community safer.”

The abundance of vacant lots has also allowed the city to sell real estate at incredibly low prices, giving priority to local residents over out-of-town developers and creating prime opportunities to reinvest in their neighborhoods.

“We’re really helping people in a tangible way," Alyssa Strickland with the Detroit Land Bank Authority told us.

The city recently started offering Detroit homeowners exclusive rights to purchase vacant lots next door to their property for $100.

“We’ve sold over 21,000 side lots for $100 exclusively to Detroit homeowners," she said.

"Our side lot program has been a major asset of transferring a tremendous amount of city-owned property back to the residents of Detroit," Bettison said.

"What's beautiful about it is that the city doesn't have to maintain it," he added. "The residents will do creative things with the lots."

In the city's east side, a local block club director started buying up vacant lots on her block and turning them into community gardens and safe spaces for kids to play.

"It is a lot of work, but it's so worth it," Kaytea Moreno Elst said. "The houses in our neighborhoods have very small backyards."

"Green space is hard to get in a city," she said. "I mean, it's hard to come by. And to own property? Land? That's something that every person wants to do."

During the colder months, she turned one of the vacant lots into a makeshift ice rink and organized donation drives to give neighborhood kids their first pair of skates and something fun to do in the winter.

In the spring, the kids will see the fruits of their labor as the first flowers start to blossom. Moreno Elst plans to help the kids organize a flower sale.

Before the city started handing the real estate over to local residents at nearly no cost, the vacant lots would sit and morph into unofficial dumping grounds.

Now, the parcels of land have someone tending to them, and one by one, the city's overall look is starting to feel more like home.

That policy sparked a sense of hope, a sense of ownership, that living in a shrinking city comes with perks for people who stay and call it home.

Journalist John Gallagher covered urban development for the Detroit Free Press for decades. In one of his recent books, he challenged city leaders in Detroit to see their shrinking city as a rare chance to spread out.

The message caught on at City Hall. Now, the Land Bank, often called the 'owner of last resort,' has become a design hub where planners strategize the next chapter of economic development with a keen eye for vacant lots or empty homes in close proximity to others.

"We offer small bundles of property," Strickland said. "If we've got a lot of inventory in one neighborhood, we might package four, five, six properties together."

A construction manager for the city stopped in the middle of applying foam insulation inside one home to discuss the bigger picture.

"We're very strategic about where we do these renovations," Robert Saxon Jr. said. "It's not by accident that we're doing this particular house."

In more than 20,000 cases, the Detroit Land Bank decided vacant homes were a total loss and knocked them down. But in other instances, especially when there was historical significance to the property, the city brought in renovation teams and prepared the homes to hit the market at affordable rates.

When the city first started to see its comeback, Saxon said, "The progress was in the downtown."

Now he sees signs of progress as renovations start to pay off.

"We're trying to do properties near stronger neighborhoods so all that development over there bleeds into some of the weaker neighborhoods. We're trying to get all of that good stuff to start happening over here."

The land bank strategy to coax investors or home buyers to move in just next door to hot areas built up and gave people a sense of momentum.

"The beauty of it now is that it's bleeding into [weaker neighborhoods], and what the land bank's been able to do with other city agencies is bleed it out so everybody feels like they're getting a taste of that comeback," he said.

Since we've returned from Detroit, the city of St. Louis rolled out plans to start adopting the side-lot program, which means homeowners will soon have the option to apply online and purchase a vacant lot next door to their home for just $100 plus application fees.

Chapter 4 Overcoming Corruption

Massive financial assistance was just about to arrive when corruption scandals rocked City Hall.

Bribery and pay-to-play schemes landed public officials in prison, gave the city a black eye and cast a shadow of suspicion on the politicians who promised to deliver results in the public interest.

The same storyline playing out in St. Louis in 2023 happened a decade ago in Detroit.

Instead of massive cash infusions from the federal government and a settlement with an NFL team, Detroit had a massive financial burden lifted when it entered the largest municipal bankruptcy in American history.

Before the Motor City could spark its comeback, it had to clean house.

“One thing I would say is don't put off reform, don't put off the tough decisions,” veteran journalist John Gallagher said.

After decades of covering City Hall for the Detroit Free Press, Gallagher sat down at an independent coffee shop and recalled the embarrassing era when the Motor City finally started to turn things around.

“Detroit's comeback is a mosaic,” he said. “There's about 100 things that have to happen.”

The first thing that had to happen was for city leaders to come to grips with the stark reality of corruption choking the city.

"We failed. We did not police ourselves,” former Detroit bankruptcy judge Ray Reynolds Graves told NBC News at the time.

“We as voters have failed to discipline our elected public officials. We were very glad to ride the gravy train as long as everybody could borrow more money and keep this thing going. Now we have to face the fact that those were all bad decisions."

Reynolds Graves guided the city through its bankruptcy proceedings in the same year federal prosecutors brought the former mayor Kwame Kilpatrick to justice.

Kilpatrick hadn’t just saddled the city’s ledger sheet with more than $2 billion in debt, he was also sentenced to 28 years in prison for stealing $500,000 from a civic fund to spend on himself.

Trust in government was at an all-time low.

“People gave up. That's part of the problem,” turnaround consultant Larry Gardner told NBC News in 2013.

"Folks had really lost faith in city government,” Deputy Mayor Todd Bettison recalled.

Bettison was a city cop for nearly three decades before Mayor Mike Duggan tapped him to take over as deputy mayor.

Now, “there's definitely hope,” Bettison said. “When folks have hope, they're going to protect what's theirs.”

During a wide-ranging interview, Bettison said the city’s strategy to restore a sense of trust in government was quite simple.

“We're working to deliver what they want,” he said. “And when you deliver on promises? Promises kept?

“It was fast, but you have to show them something,” he said. “You have to do something big. If the lights are out, you got to get the lights turned on.”

To be sure, bringing a shrinking city back from the brink of bankruptcy and out from under the cloud of corruption wasn’t just as simple as flipping a light switch; but it did take effort and relentless focus on improving small, seemingly insignificant problems that had piled up or gone ignored for decades.

“Starting with the biggest problems, the essential things, and as you work through that, you can fix it,” Bettison said. “You will build competence, you will build momentum, and you can completely turn it around just like we did.”

When we first arrived in Detroit, we found Mayor Duggan standing at the bottom of a public amphitheater fielding questions from hundreds of voters, one by one.

"I appreciate his style of being able to handle the crowd," nonprofit director John Cromer said. “He allows the citizens to vent and he responds to those vents and he does it on a factual basis."

The city had recently re-written its charter documents to require the mayor to answer directly to the public for at least one hour eight times a year. While some politicians might view such a painstaking exercise as a distraction from their duties, Duggan handled each problem as another opportunity to show voters that government can have a customer service department, too.

"I picked the right time to become mayor, there's no doubt about that,” Duggan remarked.

Duggan readily admits he didn’t bring the city back on his own. He had help from the bankruptcy court, Congress, several presidents, and from the philanthropic community who pitched in to help boost Detroit’s burgeoning revival.

But that in itself showed some political skill. Forging alliances wasn’t easy at the outset.

“The leadership has to align in some ways,” Gallagher said. “At first there was almost no one to align with. I mean, city government in Detroit was so broken.”

"It's the job of the mayor to bring the city back,” Duggan said.

Before big businesses and donors bought into his pitch, they had to see effort from him. So elected officials shouldered the initial load and started racking up wins wherever they could find them.

"We talked about, 'Here's when you can expect your streetlights on. Here's when you can expect your police response time to be cut,’” Duggan said.

When we asked Duggan’s deputy mayor to describe the secret to the city’s resurgence, he didn’t refer to Census Bureau statistics, jobs report data or wage growth. Instead, he pointed to the number of vacant homes the city had demolished and underscored the importance of repairing broken streetlights.

"When a place is dark and dimly lit, it's a problem for crime,” Police Chief James White said.

The addition of regular street lighting was just the start. Duggan persuaded hundreds of business owners to purchase high-quality surveillance cameras, wire their video feeds directly into police headquarters, and advertise their presence with bright, flashing green lights, which send subconscious signals to potential customers and criminals all over the city.

With each flashing set of green lights that go up across the city, one more business displays that its owner buys into Duggan’s safety plan, and the sense of hope and collaboration starts to spread.

“When you promise it and you deliver it, before very long, people stop talking about the past and start talking about the future,” Duggan said. “And I'm sure you saw here: right now everyone in Detroit is talking about the future."

Crime is down. Jobs and wages are up. And people like Big Keith the Barber are moving back home.

"It's definitely getting better,” Keith said.

Billionaires are buying in, too.

Philanthropist Dan Gilbert recently pitched in half a billion dollars to boost development in the city's neighborhoods.

Henry Ford's great-grandson invested a billion dollars in restoring Michigan Central Station.

"If you have an idea, people are going to buy in,” Michigan Central Innovation District CEO Josh Sirefman said. “There’s a common goal.”

There’s also a sense that the city’s collective goals benefit everyone, not just the wealthy and well-connected.

"What Ford is doing is really great,” Big Keith said. “It's going to bring a lot more diversity to Detroit."

Duggan's office aggressively advertises expanded opportunities for former felons seeking expungement, small businesses seeking grant funds, unemployed workers seeking jobs or homeowners seeking equity. In each category of Detroit's comeback, specialists at city government help first-time job-seekers, business owners, homeowners, or returning citizens speed through red tape and overcome hurdles inherent in the system.

"That's where wealth comes from,” Keith said. “Sticking together."

“We built on our strengths,” Duggan said, “and that’s what every city has to do: build on your strengths.”