ST. LOUIS — It was lost in plain sight: a Chinatown in downtown St. Louis that existed for nearly a century. It never made it to the history books and barely made the news. Now there's a widespread effort to honor these stories in light of recognizing the city's shared past.

It came about after a series of 5 On Your Side reports from the Chinese Collecting Initiative on the history of Chinatown and the discovery of old graves of Chinese residents who were not allowed to be buried in most cemeteries in St. Louis except one.

5 On Your Side has featured the work of life-long St. Louisan and architect Peter Tao, who helps lead many of the volunteer efforts of the Chinese Collecting Initiative at the Missouri Historical Society. He's written several blog posts from discovering old newspaper clippings or yearbooks and connecting the dots to uncover the rich history of this St. Louis community.

"I'm involved in many ways, just because someone has to be involved and help represent," Tao said humbly.

Tao is also the current president of OCA-St. Louis and uses his architectural skills to help in this newish accidental historian role. In his downtown office at Tao + Lee, you'll find poster-sized, historical maps and newspaper clippings backed by custom foam boards, piecing together nuanced stories of Chinatown as it stood from 1869 to 1966.

The work Tao and others have done with the Missouri Historical Society points out the rich history of the Chinese migrants to St. Louis, many of whom left California for a better life after working in harsh conditions on the West Coast to build railroads.

"The first Chinese-American immigrant to come to St. Louis came here in 1857, right before the Civil War," said Christopher Gordon, Director of Library and Collections at the Missouri Historical Society. "I don't think people quite understand how that community really developed."

That first Chinese resident was reportedly 24-year-old Alla Lee, who came to the city and married an Irish woman named Sarah Graham in September of 1858. Nearly a decade later, hundreds of folks of Chinese descent came from San Francisco and New York to work in a bustling St. Louis. At the height of its use in 1904, Union Station saw more than 100,000 passengers each day.

The St. Louis Chinatown itself was compact. It sat between South 7th and South 8th streets, from Walnut to Market Streets. It became known as "Hop Alley" but these days, many in the Asian American community avoid that term since it was a derogatory way to describe people who were "hopped up" on opium. Though opium was legal back in those days, news reports showed outsiders that Chinatown was a seedy and dangerous place.

Tao's work now shows how Chinatown was a place for community and innovation. Most of the city's laundry services were once taken care of in Chinatown. The sweltering St. Louis summers and the humid climate gave way to food entrepreneurship, including reports of a Chinese American farmer named George Lee who thrived as a regional supplier of vegetables like long beans, Chinese broccoli, and watercress.

Later, in the 1940s, a Bronze Star Medal recipient named William Hong built a $2 million bean sprout business through an early form of hydroponics with the help of the scientists from University of Missouri-St. Louis.

Urban Renewal took hold of the nation from 1949 to 1974, and Chinatown met its demise for a baseball stadium project in the late 1960s. After it was demolished, it sat empty as a parking lot for more than a decade, and by then, many in the community were gone. Volunteers with the Chinese Collecting Initiative have tried to track down many of Chinatown's descendants as few remain in St. Louis.

"In the photos that you see in articles — just like traditions of sitting on your stoop and your brownstone — everyone would just be sitting out in the alley, conversing," said Tao, walking along 8th Street where the current Spire building sits now. "It was a community."

Other triumphs include the story of a Chinese boy named Hop Leong, who lived off 8th Street and made the newspaper for excelling in all-American baseball.

"He learned every single pitch, literally possible," said Tao. Leong's skills also included the curveball and the spitball, which eventually became outlawed by Major League Baseball because it was known for giving a batter a "wet one" by altering the ball's movements. St. Louis Cardinals player Bill Doak was grandfathered in and allowed to continue using the pitch, and Leong bought a book about Doak's "spitting ball."

Leong was featured in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat in 1927 when his school team won the Public School League Championship. His team later received a visit from Branch Rickey, then vice president and general manager of the St. Louis Cardinals. Rickey was instrumental in breaking MLB's color barrier by signing Jackie Robinson and creating the framework for the modern minor league farm system.

Unfortunately, Tao discovered Leong's obituary in the summer of 1931. The boy died after getting swept away in a strong current in the Meramec River.

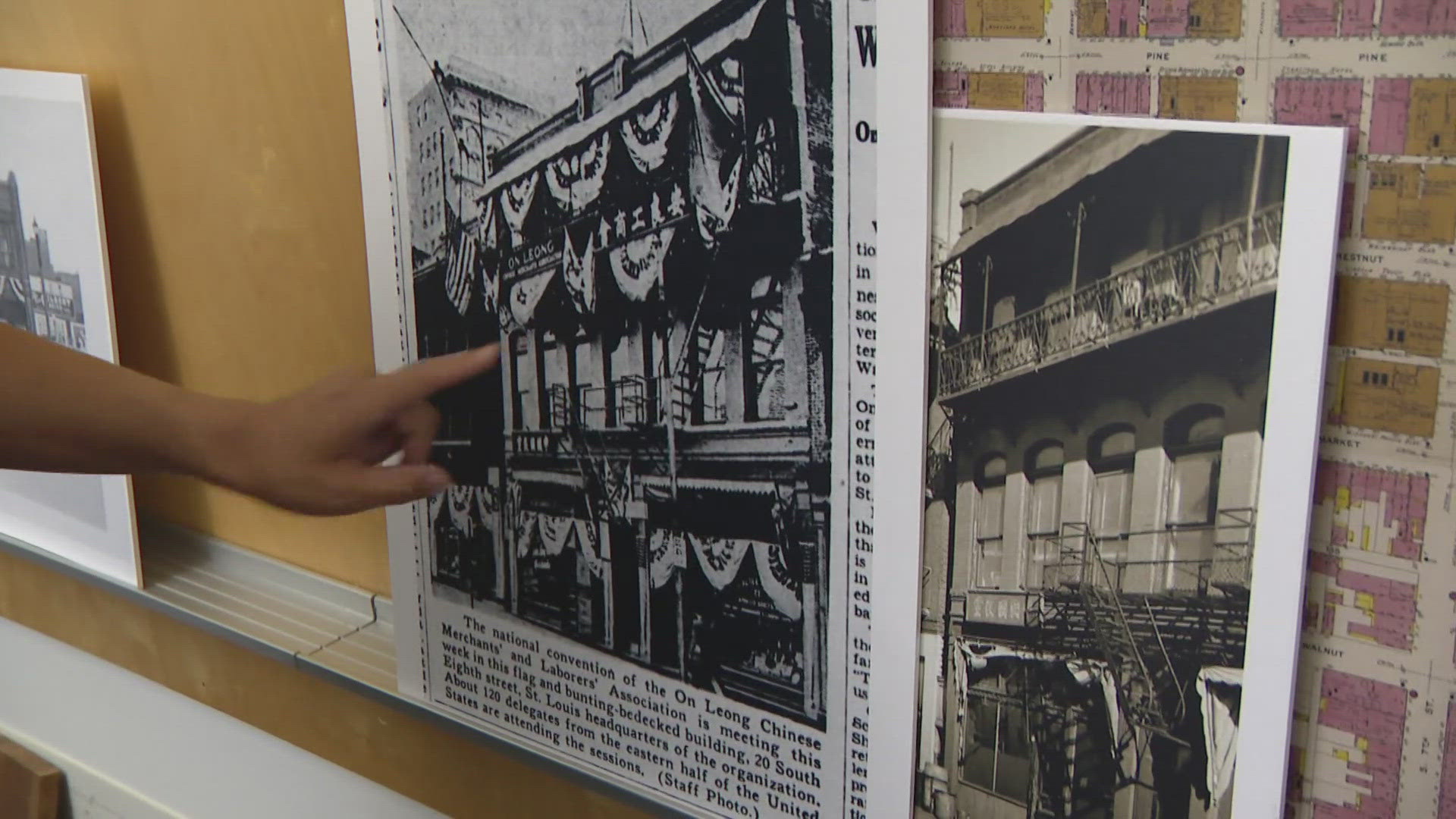

Nonetheless, from laundries to restaurants, to tea rooms, there was one famous building called the On Leong Merchants and Laborers Association, which even hosted national conventions. Because of these community legacies, it's often a pain point for many Chinese St. Louisans and other Asian Americans to see this history left out.

"There's a deep history going back to 1857 of the Chinese in St. Louis, but no one knows about it, " said Tao. "So it needs to be told."

That chance could be on the horizon with Board Bill 32. The bill is led by alderwoman Cara Spencer, who represents parts of downtown. She is proposing that 8th Street between Walnut and Market be honorarily renamed to On Leong Way, after the community center that impacted so many in the neighborhood. On Leong means peace and benevolence.

5 On Your Side brought the issue to Spencer with a simple phone call. We asked her -- did you know there was a Chinatown? And, did you know there is an effort to reclaim some of St. Louis's history?

Several community members from OCA-St. Louis, The Very Asian Foundation, Asian American Civics Scholars, Japanese Americans Citizens League of St. Louis, St. Louis Pan Asian Coalition, Washington University, and the Missouri Historical Society all worked together to form a coalition to create opportunities for some recognition. A street renaming project seemed to be fitting since 8th street served as a main street for Chinatown.

"As a lifelong St. Louisan, I didn't even realize that we had Chinatown here in our city," said Spencer. When Spencer introduced the bill on May 10, every board member present at the meeting supported its introduction.

When the bill went to the public infrastructure and utilities committee two weeks later, Tao testified and a 91-year-old community member named Don Ko shared his experiences as a former president of the On Leong Merchant and Laborers Association. Ko, who still says he works part-time appeared jubilant to share his experiences of where he worked, talked about his father's laundry business from the 1920s, and recalled specific addresses and locations of the businesses where he used to work.

"On Leong has been in St. Louis for a long, long time," Ko said with a smile. His grin seemed to stretch from ear to ear.

Spencer read an amendment to the board bill and got emotional:

"Whereas in 1904, St. Louis and the United States would joyously celebrate the Louisiana Purchase, the World’s Fair, and invite China to participate in the Fair, yet confine," Spencer pauses and waves her hands as she steps back from the podium.

"I didn't expect to get choked up," she said.

She continued, "...yet confine their Chinese workers to the Fairgrounds, where due to the aforementioned Exclusion Act were granted temporary admittance to the U.S for only the duration of the Fair, and each worker with a $500 bond attached to their head to ensure their return to China upon the close of the Fair. The total of which would be handcuffed in pairs, regardless of illnesses, and marched to the Wabash train station to board the guarded trains to San Francisco.”

Spencer quickly paused again, visibly emotional.

"A dark portion of our city's history," said Spencer. "We often think of the World's Fair, and I still do, as such a triumph for our city-- an era of opulence and one of great success. But certainly, I think it's important for us to recognize on the backs under which tragedies that opulence was. I think this is an important admission to the board bill in recognition of all aspects of that history."

The amendment was not only adopted, but Anne Schweitzer, the committee chair and Ward 1 alderwoman asked to be added to the bill as a sponsor. Alderwoman Daniela Velazquez of Ward 6 also weighed in and said she was stunned when she first learned about Chinatown about a decade ago.

"I think it's important that we can't forget our past when we look at our future," said Velazquez. "When we talk about these conversations about housing and displacement, we're looking back on consequences of decisions made-- that I would imagine that we purposely displaced a community. And when we talk about growth and how important new Americans and immigrants are to the growth of the region and the growth of the country, we also have to think about and reflect on our actions to make sure we're not displacing communities -- not just immigrants--any communities."

Alderman Michael Browning, co-chair of the public infrastructure and utilities committee and co-sponsor of the street renaming project, said he encourages everyone to visit the Missouri History Museum to visit the newly updated 1904 World's Fair Exhibit along with supporting the bill.

"This will be a wonderful way to remember the history of St. Louis and hopefully spark that curiosity in others as they ask that question, 'What happened here?' said Browning. "I think that St. Louis' history is rich and wonderful, and it's all the people along the way that made it that way."

The board bill itself still has to move through a process that could take a few weeks, and there still could be objections. Tao hopes it's the first of many steps to reclaim Chinatown's place in St. Louis history. Tao is also working with professors at Washington University to create a digital experience that would allow users to see old buildings juxtaposed against modern buildings.

Spencer is also hopeful this renaming project is the first of many steps to recognize Chinatown.

"I'm hoping that with this effort, we can not only educate our policymakers, but provide some signage, and really some historical markers that can educate the general public on what was here," said Spencer. "And to help imagine that history."

Tao is already envisioning what could be.

"I think it'd be so cool to have just like the ghost of that building sitting here and then lit up at night," said Peter as he points above the Spire building.

What may have started serendipitously now has an intentional future as momentum builds throughout the community. It is becoming a united vision with a new understanding of a shared past. For Tao, he's just waiting for the day people will stop asking -- "There was a Chinatown in St. Louis?"