TROY, Mo. — September 11.

The opening of the U.S. Embassy in Kabul, Afghanistan.

Benghazi.

The Boston Marathon bombing.

The evacuation from Afghanistan.

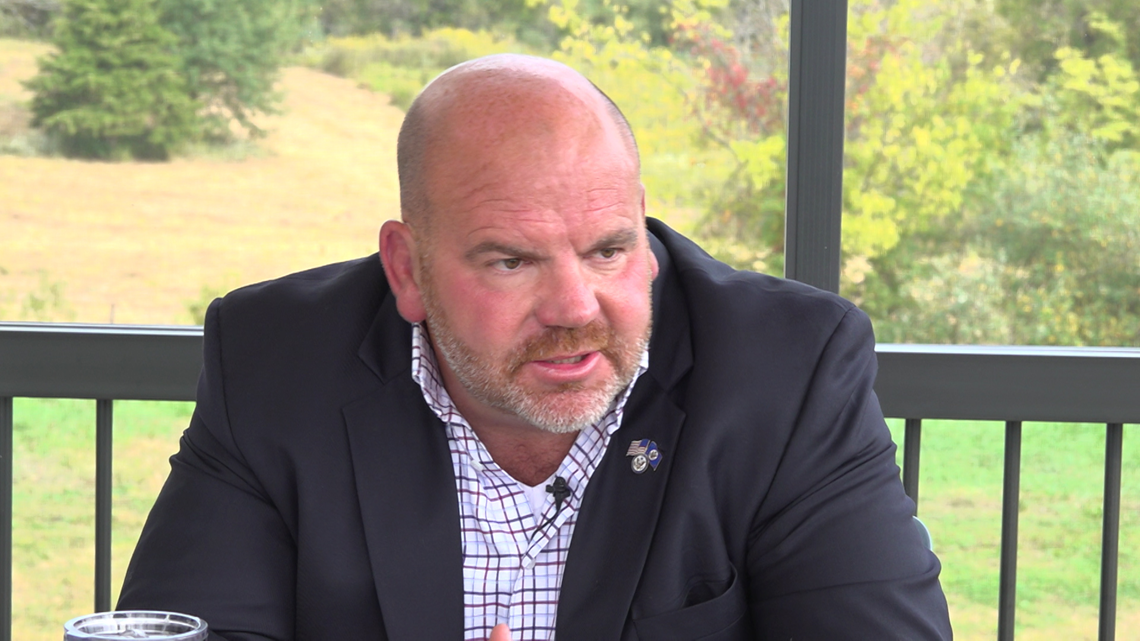

Name virtually any major historical event during the past two decades, and chances are, Bill Wommack has been a part of it.

His most recent assignment – and abrupt departure from Afghanistan – brought his career as a Diplomatic Security Special Agent for the State Department full circle in a way he never imagined.

“I got to see the flag go up and go down,” he said.

Wommack shared his personal experiences as one of about 2,200 Diplomatic Security Special Agents worldwide with 5 On Your Side to give a glimpse into the often overshadowed and little-known arm of federal law enforcement.

It’s their job to keep foreign dignitaries safe and protect the integrity of U.S. travel documents. Because of the agency’s international footprint, agents also investigate transnational crime including human trafficking, counterterrorism and cyber security breaches.

Federal law enforcement agencies like the FBI, CIA and DEA may be household names, but the State Department’s Bureau of Diplomatic Security has the largest global reach of them all.

Public affairs specialists from the State Department monitored Wommack’s interview with 5 On Your Side by phone to ensure he didn’t stray from sharing only his personal experiences and into policies, procedures or his opinions.

And there are plenty of experiences to share.

He toured ground zero with former Secretary of State Colin Powell. Helped investigate the Boston Marathon bombing. Lived with the late Ambassador Christopher Stevens who was killed in a terrorist attack in Benghazi, Libya. Testified during closed-door Congressional hearings about the Benghazi attack.

And most recently, Wommack helped during the United States’ evacuation from Afghanistan – an experience that has left him emotional as he nears the end of his career.

“I’m still pinching myself,” he said. “It feels like it was a bad dream.”

A career is born

Wommack was a Marine serving as an embassy guard in Geneva, Switzerland and Kuwait with dreams of becoming an FBI agent in the late 1990s.

“I was hoping to use my charm to get a foot in the door with the bureau,” Wommack quipped.

The FBI has legal attaches working at some embassies, but there weren’t any at the embassies where Wommack was stationed.

Instead, he learned about the Bureau of Diplomatic Security following the East African bombings, which rocked U.S. embassies there killing 224 people.

The attacks happened eight years to the day American troops arrived in Saudi Arabia in response to Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait – a deliberate move by Al Qaeda.

He ended his tour as a Marine in December 1998 and started the six-month academy to become a Diplomatic Security Special Agent that following year. The agency has offices in more than 270 locations throughout the world. Domestically, agents like Wommack work in 29 cities.

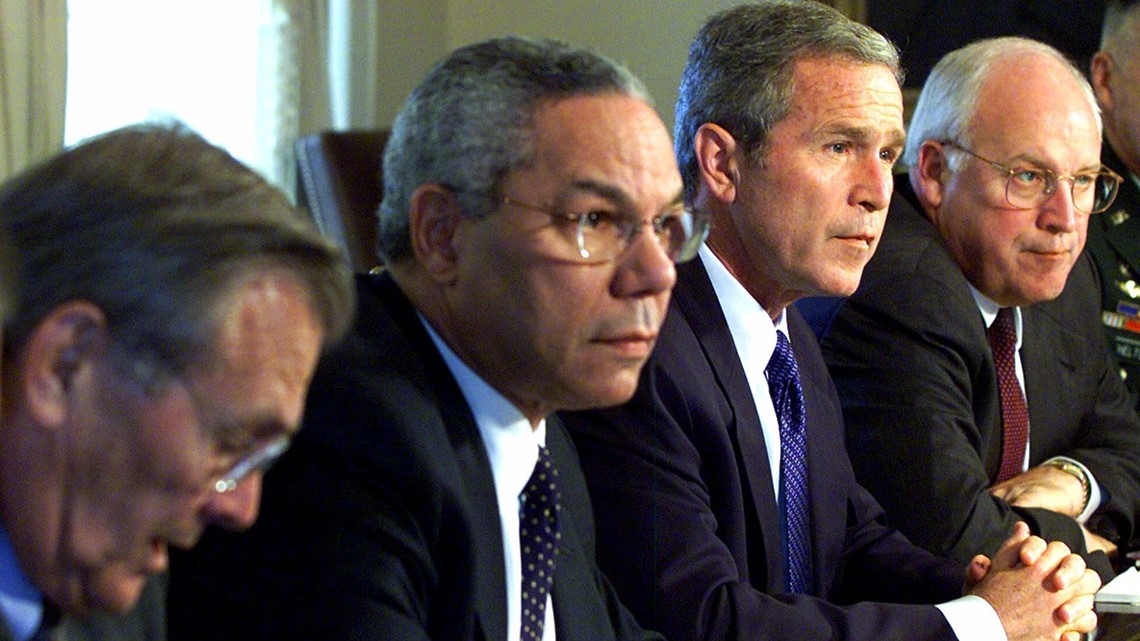

Upon graduation from the academy, Wommack started out stationed in Dallas. He spent a year assigned to then-Secretary of State Madeline Albright. He then spent two years with her successor, Colin Powell.

He was returning from a trip with Powell on Sept. 11, 2001 when they learned about the terrorist attacks. Days later, Wommack walked with Powell at ground zero.

“It almost felt like martial law, there were military checkpoints everywhere,” he recalled. “We had to do the coordination with D.C. Metro and Park Police to coordinate (Powell’s) arrival.

“It was surreal. There were all of these lights and monuments and not a person on the street. Nothing but our red and blues flashing through the streets. It was gut wrenching.”

Wommack said the smell has stayed with him.

“I'll never forget the smell of burnt steel or whatever it was, I don't know,” he said. “The flag was hanging up there and seeing all the police and fire and fire departments all working together, that’s the key takeaway, it was an awesome experience to see how everybody united for one focus.”

Just a few months later in early 2002, Wommack was with Powell for the opening of the U.S. Embassy in Kabul, Afghanistan.

“From a U.S. veteran's perspective, it was nice to see us going in and raising the flag,” he said. “The embassy had been there years before, so there was already a structure in place, but we clearly had to do some work to fortify it.

"It was just a cool moment, even from a State Department perspective, because now we were kind of putting a placeholder in a country that needed our assistance.”

Changing scenery

His assignments changed about every two years.

He was the Assistant Regional Security Officer in Madrid, Spain, when the train bombings happened.

In Bagdad, he was the deputy to the High Threat Protection Office within the Regional Security Office, managing all of the security contractors, including Blackwater. He also got married to his wife, Brandi, there.

“I was the No. 2 in that office,” he said. “I had 30 teams of contractors.”

After that, he went to Atlanta to serve as the liaison from the State Department to the FBI Joint Terrorism Taskforce. It was his job to provide the State Department’s resources to any kind of counterterrorism case work.

He also served as the Regional Security Officer in Lahore, Pakistan.

He and his family then moved to Atlanta, Georgia, in 2010 to work domestically. But when agents like Wommack are stateside, they could be called up at any time to help with security details for all foreign dignitaries.

Sometimes, that means planning security for visiting dignitaries, ambassadors and royalty – such as Prince William and Duchess of Cambridge Kate.

“That was great,” Wommack said of meeting the royal couple while working on their security detail in California. “I got to go to this fancy polo match and rub elbows with the Bushes.”

In 2010, duty called him to Benghazi.

One year and one day before Ambassador Christopher Stevens was killed, Wommack moved into the complex where Stevens was living. The first thing he did was change Stevens' morning routine.

“We can’t do things time and place predictable,” Wommack said. “So, the first thing I did when I met Chris Stevens, I said, ‘I’ll tell you, boss, I hear we run every day at 6:30.’ And he said, ‘Yeah, that's what we've been doing.’ I said, ‘Well, how about tomorrow, we do something different?’”

Wommack changed the timing on the runs and the routes for the two months he spent there and coordinated Stevens' travels throughout the region.

“I was responsible for getting him out and about and meeting locals,” Wommack said. “He was somewhat of a rock star. He knew the language."

By the end of his 60-day deployment to Benghazi, Wommack said he had grown close to Stevens – especially during their runs together.

“I’m not a runner, but he was one of those guys you kind of do what you’re told,” he said. “And on my last day with him, we ran eight miles.”

Wommack paused recalling the moment as tears welled in his eyes.

“I think the biggest kick in the shorts was he asked me to be his (Regional Security Officer) because he had gotten the nod to become the Ambassador in Tripoli,” Wommack recalled.

But the timing wasn’t right for Wommack, who had just spent a year in Lahore, Pakistan not long before his assignment with Stevens.

“I couldn’t do that to the family,” Wommack said. “He kind of let me be me.”

Thoughts of "what if" still haunt him.

“I think that I would’ve done things differently and maybe it wouldn’t have…” Wommack said, trailing off. “Maybe it wouldn’t have happened.

“But that’s water under the bridge.”

International travels

Another assignment brought Wommack to Boston. He was the Acting Special Agent in Charge when the Boston Marathon bombing happened, and his team helped identify and bring the Tsarnaev brothers to justice.

“It was an awesome experience from a service standpoint,” he said. “I was able to leverage headquarters into giving us extra money.

“So we got 30+ agents and analysts to come in to help the FBI investigation. Never, and to my knowledge, has this ever been done before in the States. We worked 24/7 at the command post. The FBI and our analyst section was instrumental in identifying potential suspects.”

Wommack then got word that a position had opened in Barbados. He called his wife asking if she thought it would be a good place to move with their kids.

“It was March and it was snowing and he’s like, ‘Do you want me to put in for Barbados?’” she said. “And I'm like, ‘Why are you even on the phone with me?’”

There, Wommack served as the Regional Security Officer for all of the Eastern Caribbean, one of the largest regions from a security perspective in the world, he said.

“There was a lot of challenges because each of those islands were different and they were all managed by different folks and different perspectives and different backgrounds and different capabilities,” he said.

In addition to those duties, Wommack said some of his most rewarding work on the islands was working with some of the hospitals and schools, which were in poor condition. His division helped start "stranger danger" types of safety programs in the schools.

From there, it was back to the United States – to work in Washington, D.C. as the Personal Recovery Section Chief. In that role, he was responsible for overseeing the recovery of American hostages worldwide.

“There was a huge push by Congress to find out why the United States at large wasn’t able to identify who had our people,” Wommack said. “President Obama set up a new endeavor to have the White House and the FBI formulate a task force and interagency called the Hostage Recovery Fusion Cell.”

Wommack went to regular meetings at the White House, letting himself in and out with a swipe of his badge.

“It was pretty neat,” he admitted. “We were fortunate we were able to bring home a couple captives while I was there on assignment.”

He deployed again to Afghanistan for about a year, where he said he recovered two more hostages.

Coming home

By June 2019, Wommack got another chance to move back to Missouri. He and his wife built a home just a few hundred yards from the home where he grew up in Troy.

As the United States’ deadline to leave Afghanistan approached, Wommack volunteered to help.

“I went over there primarily because I just got back and I knew the lay of the land and I knew lot of the key players and I went over there to oversee or kind of manage the retrograde of the military because we knew that they were pulling out,” he said.

But he had no idea how abrupt the departure would be.

“I, having been there just a year prior, would have bet my salary that we wouldn't have ever had to go through that process," he said. "It was just confusion.”

He landed in Kabul, Afghanistan on Aug. 10 for what was supposed to be a 90-day assignment.

It lasted five days.

He then unexpectedly boarded a C17 headed to the military base in Doha, Qatar – 1,155 miles away from Afghanistan.

“We loaded that bird like a bunch of cattle,” he said using slang for the massive military aircraft. “We had to line up and they put a tarp strap over your lap.

"There were no bathrooms and they gave you a bottle to pee in. There were babies born on those planes.”

For three weeks in Doha, Wommack facilitated the arrivals of thousands of refugees from Afghanistan.

Many were seen clinging to military planes as they took off from Kabul.

“A lot of those folks didn't ever have a clue what was going on,” he said. “I mean, they knew that they were going to the mothership or going on to the land of milk and honey, but they had no idea how they were going to get there.”

He said donations started coming into the tent cities, including dollar-store types of toys for the children.

He noticed as one little boy clung to a plastic horse.

“He thought it was the best thing ever,” he recalled. “And I thought, ‘Surely this, this excitement will go away. This is an anomaly.’

“And fast forward about a week. He was still there. He was at a camp. I went to this camp to check in with somebody, and he still has that little plastic horse.”

Emotion returned to Wommack’s eyes recalling the moment.

“It was touching to see some of their eyes, their faces,” he said. “Bewildered might be a good word for that. Maybe bewildered optimism.”

Wommack said he wasn’t fearful for his own safety.

Back at home, his wife was in knots.

“I still have to sit on the couch and watch a movie with the kids and pretend that like, everything's great and I'm not freaking out and crying and texting and dying on the inside,” she said.

She told their children not to complain about their Internet service being spotty when their dad got home — given all the struggles he had just seen other children endure.

“They didn’t listen,” he quipped.

He’s now working for the St. Louis field office, which supports the Chicago field office.

His phone could still ring at any moment, with another temporary duty assignment to another country. For now, he’s content working from home.

“It was interesting to be part of that history,” he said. “I've had a good, good run.”

A run, he added, that wouldn't have been possible without the support of his family.