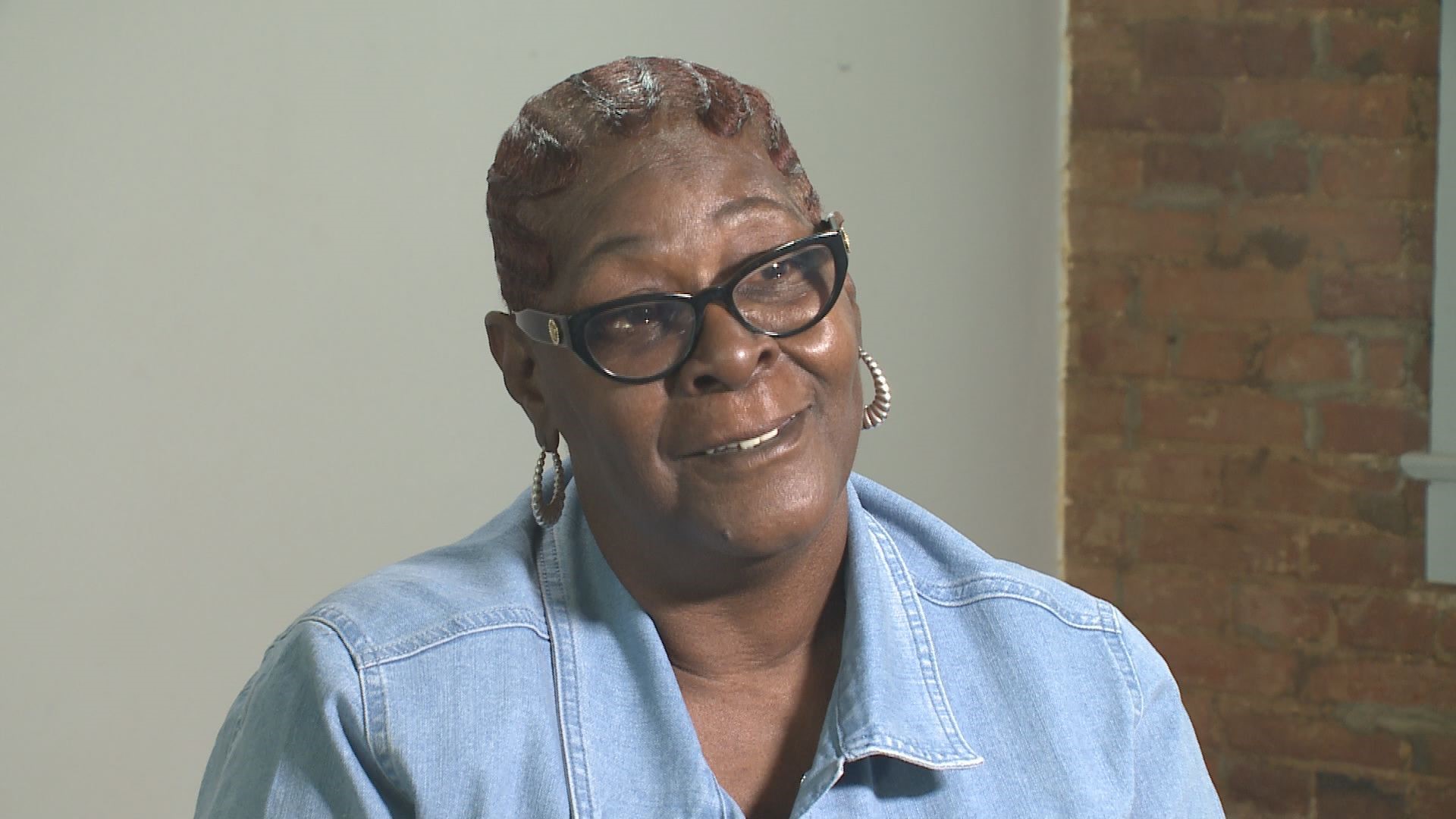

ST. LOUIS — Barbara Baker remembers walking out of prison on Oct. 3, 1995.

“God himself couldn't have made me believe this is where I'll be,” she said, as she stood outside a transitional housing facility for women trying to pick up the pieces of their lives after serving time just like Baker did.

“This is the Barbara Baker House,” she said, as she pointed to the sign that says so inside the door.

Baker, 70, said she was addicted to heroin for more than 25 years of her life. She has more than 18 felony convictions on her record. And she’s been arrested more than 55 times.

“And that’s not counting the misdemeanors,” Baker said.

Now she’s an advocate for women working to turn their lives around and one of nine people who will advise St. Louis Mayor Tishaura Jones on how best to run the city’s jails.

Having once been an inmate in them, Baker said her lived experience makes her qualified for the volunteer opportunity.

“I could be a voice for the women inside of the jails,” she said. “I filled out the application and to my surprise, I got appointed.

“I was shocked that I got appointed because, you know, men and women coming out of jails, we never quit doing time. I haven't been arrested in over 30 or 35 years ... but my record still is a sticking point in some things, so I didn't think I would get picked for it, but I did. So I'm humbled and thankful for that.”

A civilian task force formed under previous Mayor Lyda Krewson following riots at the downtown City Justice Center recommended a more permanent civilian oversight committee be appointed to keep tabs on the issues at the facilities.

The civilian oversight board has not yet had its first meeting, as unrelated controversies involving some of its other members have caused delays.

Baker said she is eager to get started.

“I’ve been in and out of the Workhouse so many times, I can’t count them,” she said.

The Workhouse—as some call it—is formally known as the St. Louis Medium Security Institution. It's located along Hall Street in north St. Louis.

Jones, U.S. Rep. Cori Bush and St. Louis Circuit Attorney Kim Gardner toured it last year and called conditions there “inhumane.” Jones ordered it be closed July 1.

That sent about 150 detainees into the City Justice Center, where faulty locks allowed inmates to get out of their cells and riot four times in just about as many months in 2021.

In addition to the riots there, corrections officers have been charged with allowing inmates to assault each other and bringing in drugs including fentanyl, which caused three nonfatal overdoses.

One inmate recently died of a pulmonary embolism.

The mayor’s office now calls the Workhouse a different name: the Annex.

It now houses all of the city’s female detainees, a number that hovers around two dozen.

Baker now walks in there on her own terms: to mentor the women there and tell them about the organization she has worked for during the past two decades.

The mentoring also helps Baker understand the staff’s concerns, too—another point of view she hopes to bring to the mayor’s attention.

She also sees a younger version of herself in the women who are being held there every time she goes.

Tears stream down her face as she relives the cycle of relapse she once lived.

“I would get out of jail, I would I would get a job, I would get a house, I would get my children, and I would relapse in that order,” she said, her voice never cracking despite her tears. “And that's because I was always running out doing what society said I should come out and do, and I didn't do the work that I needed to do on me.”

Baker then met a woman who was forming the Center for Women in Transition.

She’s now its advocacy director.

She has her own office.

Pictures of Baker standing with the area’s political leaders including former governors and local prosecutors adorn the walls.

“We work with women coming out of jails and prisons and we try to offer them something different, because if you don't give them something different, you can’t expect anything different,” she said.

The organization named one of its transitional houses in her honor seven years ago.

She greeted some of the ladies who live there on a recent afternoon.

“Hello, ladies, how you doing?”

“Good. How are you Ms. Baker?” one woman answered.

Baker said most of the women who live there have children, but they only come for visits.

The goal is to let the women heal themselves mentally from a lot of the trauma that drove them into a life of crime before they try to get their children back full-time.

Baker gave birth to her son in prison.

She vividly remembers how she was given five days to spend with him, nursing him and bonding with him until her mother came to get him.

“They went out one door with him and I went out the other,” she said, tears returning to the dried paths of the others on her face. “It felt like he had been snatched from me, like kidnapped.”

Baker also has a daughter, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. She is proud to bring the children to see the house named in her honor.

“This is something they can be proud of,” she said. “They don't have to be ashamed of who I was.”

Serving on the jail oversight committee is something else her family can be proud of.

“When I look back over my life and I look at where I'm at today, I had to go through what I went through to be where I am today, those lived experiences, you know, to give women hope that change is possible,” Baker said.

And she wiped away her tears.