Rumors surround Illinois' 'haunted' Hartford Castle. The true story is much stranger

The real story of the Castle is, in many ways, even more remarkable than the rumors that have swirled for the past century.

St. Louis Star and Times circa. 1913

Every town has that one odd house everyone thinks is haunted. For generations who grew up in the Metro East, that house is, and always will be, the "Castle" in Hartford.

Teenagers throughout Granite City, Edwardsville, Wood River and Mitchell told tales of the ostentatious and conspicuously out-of-place mansion in the wide-open river bottoms of rural Madison County. The grounds inspired stories of intrigue and wild imagination, but none of the rumors come close to the property's true history.

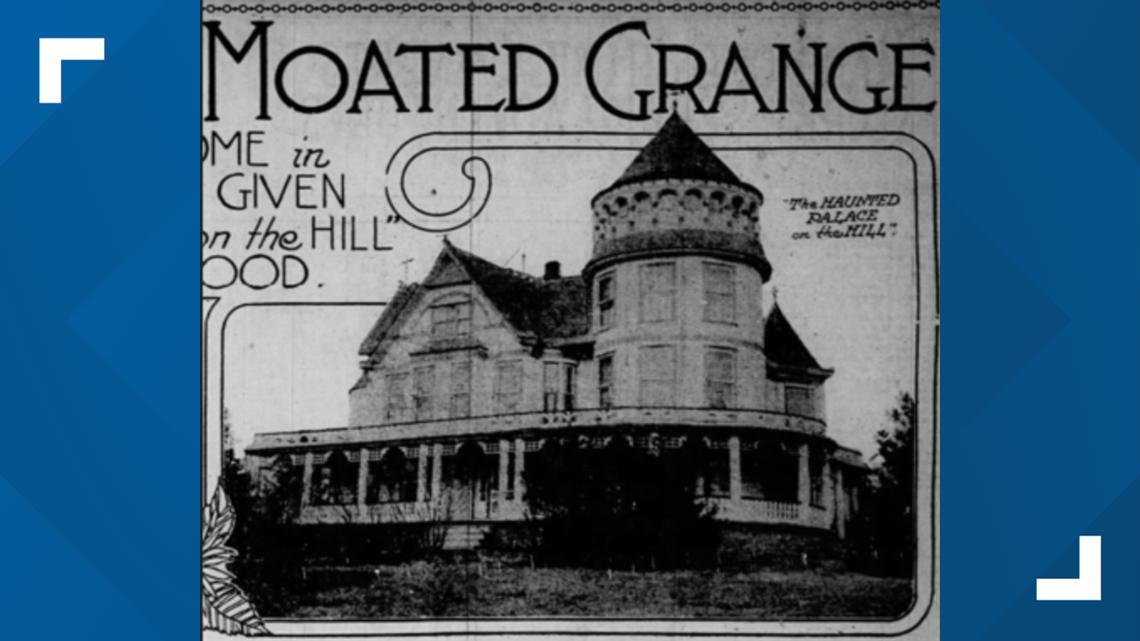

The fake tale that's stuck for more than 100 years goes like this: The Castle was built by an eccentric French man for his English wife who died before she could see the finished estate. Overwhelmed by grief, the wealthy builder abandoned his majestic manor while her ghost lingered to haunt the place.

None of that tale is true. The man who built the Castle was not from France and did not build the house for his wife, who was not from England.

The real story of the Castle is, in many ways, even more remarkable, as told by numerous local historians, public records and newspaper articles. The history is rooted in real-life incidents of dreams, death and deception surrounding spirits of the drinking and spirits of those passed on.

Love and loss Hartford Castle's origins

The Castle was birthed from the unbridled imagination and seemingly limitless means of one man, John J. Biszantz. His story begins not in France or England, but in Marietta, Ohio.

Biszantz’s grandparents immigrated to the United States from Germany in the 1830s and settled in southeast Ohio. Biszantz was born the day before the first shots of the Civil War in 1861. As a teenager, his family moved to Evansville, Indiana, where he became a carpenter, saved up his money and in 1882 set out to find his fortune in St. Louis.

St. Louis was the place to be, and Biszantz found more than work and money. He met a carpenter’s daughter named Lillie Black. Lillie was not from England, but Brooklyn Street in north St. Louis. Biszantz and Lillie hit it off, married in May 1883 and built a home of their own. Rather than settle in, they leaned into the red-hot real estate market of the time and sold the house for a profit. That experience set the couple on a prosperous path of buying and flipping property long before it was cool.

For the next 13 years, the Biszantzs would buy and sell real estate to amass a huge fortune. Along the way, they paused to add an adopted daughter named Edna.

Life was grand until August 1890, when Lillie died at the age of 29. Stricken with grief, Biszantz trudged along for a few more years before he decided to shut it down and retire at the age of 35. A single father with a lot of money and a lot of time on his hands, Biszantz started mulling his next project.

Construction How Hartford Castle was made

Back in the 1890s, the river bottoms between East St. Louis up to Alton and over to Edwardsville were just a few farms filling the space between countless trees. Biszantz found a 40-acre plot of land right in that area. Where most saw just another field to farm, Biszantz saw possibilities.

Biszantz’s purchase of the property is recorded in the Sept. 22, 1896, edition of the Edwardsville Intelligencer. More than a mansion, he envisioned a huge estate with grounds, gardens, pools and porticos -- something that resembled a luxury resort more than a private residence. There is no way to know exactly what inspired this grand vision: If it was a tribute to the memory of his late wife, a palace for his princess Edna or something for a rich guy with gobs of money to dump money into.

There was nothing subtle about this build. This was a home designed to be noticed.

Work started before the ink was dry. 60 teams of men and horses shoveled up a mile-long, 20-foot-wide moat around the property. Dirt from the dig was used to create a hill on which the house was built.

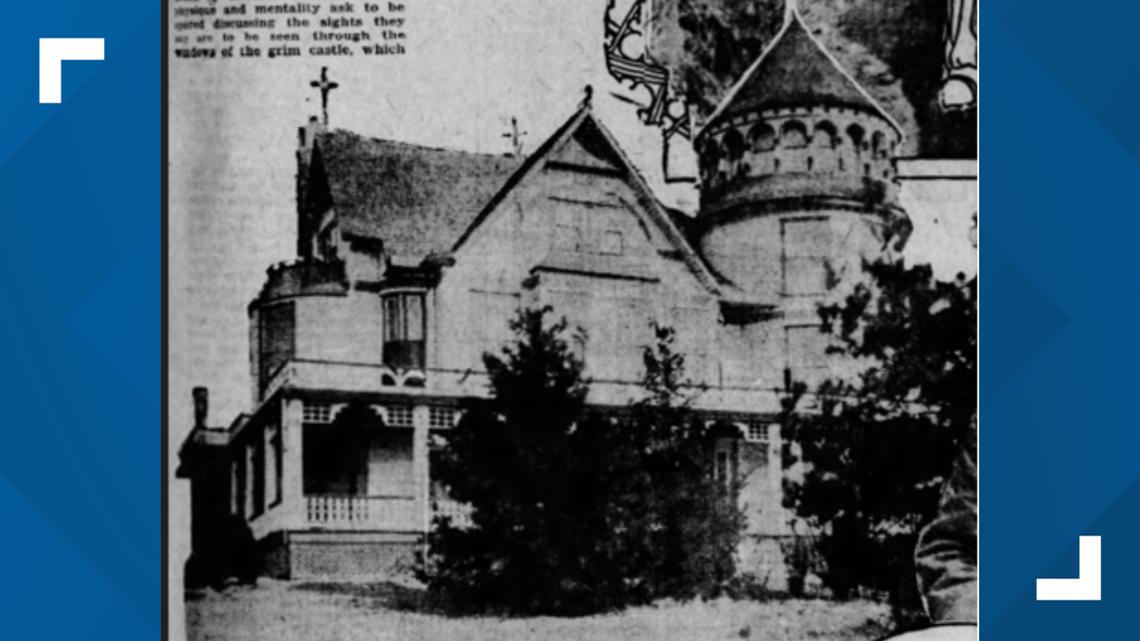

The three-story, 16-room mansion was made of wood, but crafted to look like stone. A bold red roof capped the bright white structure and a covered porch wrapped the first floor like a big belt. The most fascinating feature of the front façade was the outsized, four-story tower positioned on the southwest corner of the home, facing the railroad tracks for everyone clacking by on the trains to see.

Inside, fine wood floors were accented with expensive carpets. Walls were adorned with valuable textiles and paintings. The first floor was an open floorplan with mirrors strategically placed to reflect light into dark nooks and make big rooms appear even bigger. The second floor of the tower contained a pool hall, which sparked a lot of gossip in the community. An observation deck at the tip top of the tower gave an unhindered view of the grounds below and the wide expanse of nothing beyond the moat.

The grounds were a maze of pathways and babbling brooks, accentuated with statues, fishponds and stone gazebos. A three-story water tower was designed to look like a three-story Castle tower. The tower was topped with a windmill used to draw water up into a tank and provide pressure for the home’s indoor plumbing. A deep well and reservoir kept the moat full and the koi content. Streams flowing off the main moat created a chain of small islands connected by stone paths and arched footbridges. A statue of a reclining dog at the edge of one island stood, or rather laid, watch over one of two drawbridges. One bridge on the south end led to a long driveway, with the west bridge leading to the railroad tracks and a train depot built just for the estate.

Biszantz allegedly spent more than $100,000 on his new home, equal to more than $3.7 million in 2024. He called his mansion Lakeview, while farmers on the plains and passengers on the trains called it "The Castle."

Scandal How "Lakeview" became the "Castle"

Biszantz, his daughter, and their close friends lived at Lakeview year-round at first but later opted to migrate west to Los Angeles for the winter. While they were away for those long cold months, the Castle sat empty and began stirring rumors and filling local noggins with notions of the place being haunted.

The specter speculation went into overdrive when it was learned that Biszantz was attending séances in Los Angeles, trying to connect with the spirit of his long-lost wife. In 1912, a do-good citizen’s group called the Justice League persuaded Biszantz to help them debunk sketchy spiritualists working in Southern California. Biszantz went along with the plan thinking it would prove the paranormal parties were legit and the veiled apparition that he spoke with and even kissed on one occasion was truly the materialized spirit of his wife.

At a séance on the evening of March 3, the trap was set, the ruse revealed and the arrest of a larger-than-life medium named Carrie Sawyer made national news. The stories pegged Sawyer as a charlatan preying on the weak-minded and portrayed Biszantz as a grieving, gullible and wealthy chump.

Embarrassed, Biszantz hightailed it back to Illinois and took refuge at Lakeview. Reporters tracked him down and local newspapers reeled off long writeups about his eccentric experiences and his "creepy" Castle while juicing their stories with increasingly sensational, unattributed reports of ghosts on the grounds.

In February 1913, a burglar was arrested after breaking into and spending the night in the empty residence. While in jail, the bold bandit told any reporter that would listen a wild tale of being coaxed into the house by a mysterious ghostly woman. Once inside, she disappeared and left him trapped in the mansion with its maze of mirrors and frightening ghouls seen and unseen.

Most newspaper reports ignored the facts of the case and leaned hard into the ghost angle, resulting in stories that would be perpetuated and exaggerated for years to come.

Decomposition How the Castle was abandoned

The furor that followed the burglary was the last straw for Biszantz, who sold Lakeview to an educator from St. Louis named Eugene Rinaldo for $50,000.

Rinaldo and his partners turned the Castle into the Lakeview Military Academy, which lasted one year. Before the investors could pivot and reopen as a wellness spa, Rinaldo defaulted on the mortgage, prompting Biszantz to sue and retake possession of property.

A group out of Alton then bought the estate with plans to turn the Castle into a roadhouse. When that project failed, Biszantz repossessed and sold Lakeview again, to Eugene Rinaldo, again. By this time, Rinaldo was claiming to be a doctor with dreams of turning the compound into a sanitarium, which failed.

By the 1920s, Biszantz was out of the picture and living large full-time in Los Angeles while the Castle sat empty. Trains would come and go, and occasionally, passersby and the curious would cross the drawbridges to take a look around. Prohibition then went into effect and the legend of Lakeview evolved from spirits in the moonlight to spirits in the moonshine.

Most nights, Lakeview was very dark and very quiet until Nov. 15, 1924.

Local farmers saw the interior of the Castle glowing with lights, music echoed across the fields with cars lined up to cross the draw bridge. According to newspaper reports, 66 people were invited to attend a party for a wild night of drinking, dancing, and gambling.

The host of the get-together was a notorious east-side gangster named “Dressed Up” Jimmy Overstreet. Parking attendants were on hand to guide cars where to park, and guests were ushered into the house. Like something straight out of a movie, one by one they were led to a backroom, relieved of their cash and jewelry and held hostage until the next morning. Jimmy and his gang reportedly got away with $8,000, or about $140,000 in 2024. Years later when Jimmy was arrested in Detroit, he spoke of the Lakeview heist as his finest moment.

In 1930, a clerk at the Lakeview train depot was robbed, tied up, his head wrapped in tape and dumped in a muddy cornfield. The estate’s reputation suffered some collateral damage during the 1920s and '30s when the similarly named but totally different Lakeview Inn in Mitchell was grabbing its share of headlines with stories of moonshiners, gangsters and murder. Fairly or unfairly, these incidents plus the original ghost stories would be everything a big house with a moat needed to level up to local legend status.

Mato (Matt) Vidakovich, a Croatian immigrant and grocer from Wood River, purchased the property around 1925 and lived at the estate with his family. After the train depot was closed, getting to Lakeview was not nearly as convenient for the public, but the owners were always dealing with trespassers. The grounds and house were a lot to manage and maintain and eventually, Lakeview was abandoned for good.

In the years that followed, the Castle would be stormed by waves of teenagers and college students looking for a place to party. Set back in the trees, out in the middle of nowhere, it was the perfect place to raise a ruckus. Vandals prowled the estate and stole anything they could carry and busted anything they couldn’t.

In 1973, someone set fire to the house, reducing it to a pile of ash. Stone columns and arches that once ringed the observation deck at the top of the home’s tower fell 50 feet, landing with a thud in the ground, where they would be snatched up and carted away as souvenirs.

What remains "Elegant Reminder of the Past is Destroyed"

John J. Biszantz did not live to see the demise of Lakeview. The Castle creator died in June 1954 in Los Angeles at the age of 93. A man whose life went from simple to sensational outlived his daughter and her husband and died alone in a nursing home.

The funeral notice in the Los Angeles Times noted the services were “strictly private.” No other funeral announcement that day or even that week included such a notation.

Biszantz was cremated, his ashes returned to St. Louis and buried next to his wife, daughter, and son-in-law beneath a large marker in the Bellefontaine Cemetery.

For more than 125 years, the Castle has provided local residents with irresistible fodder for ghost stories too good to be true and true stories often too wild to be believed. Today, the site is private property and, according to Madison County tax records, still owned by the Vidakovich family.

Various YouTubers have documented visits to the site where all that remains of the once grand estate are a pair of stone gazebos, nondescript concrete foundations, a couple of unremarkable wells and an empty fishpond. Through the years, some of Madison County’s finest have paid their respects by tagging everything with graffiti and nonsense.

The old drawbridges are gone, and a felled tree is the only way to traverse the moat, outside of slugging through hip-deep, stagnant water. The statue of the dog, for generations a novel focal point of the grounds, has been nicked and now sits in the front yard of a house a few miles away on Meadowlane Drive.

It is impossible to see what was once Lakeview without trespassing, which was and still is illegal. Any trespassers will now only be greeted by mosquitoes, ticks and incredibly thorny shrubbery deftly weaved across any still-paved paths.

Lakeview may not have been any bigger or more elegant than some of the grand old homes along St. Louis Street in Edwardsville. But, location is everything in the real estate game, and Biszantz built his mansion in a place where you couldn’t ignore it, with a tower to be seen, and most importantly, that single feature elevating any residence to rock-star status, the moat.

The moat, remarkably, even more than 100 years later, is still visible on Google Maps, shaped like a giant triangle with rounded corners, nestled up against the railroad tracks on the north side of New Poag Road. That moat is the only reminder of one man’s dream and a lingering link to a local legend.