JEFFERSON CITY, Mo. — Proposed legislation to regulate intoxicating hemp products could potentially ban the majority of the Delta-8 drinks and edibles on the market in Missouri today, the state’s top marijuana regulator told an industry meeting late last week in St. Louis.

“This is really an unanswered question,” said Amy Moore, director of the Missouri Division of Cannabis Regulation.

Moore was among a panel of speakers at the National Cannabis Industry Association’s Missouri Stakeholder Summit who discussed legislation in the state House and Senate that would create the “Intoxicating Cannabinoid Control Act.”

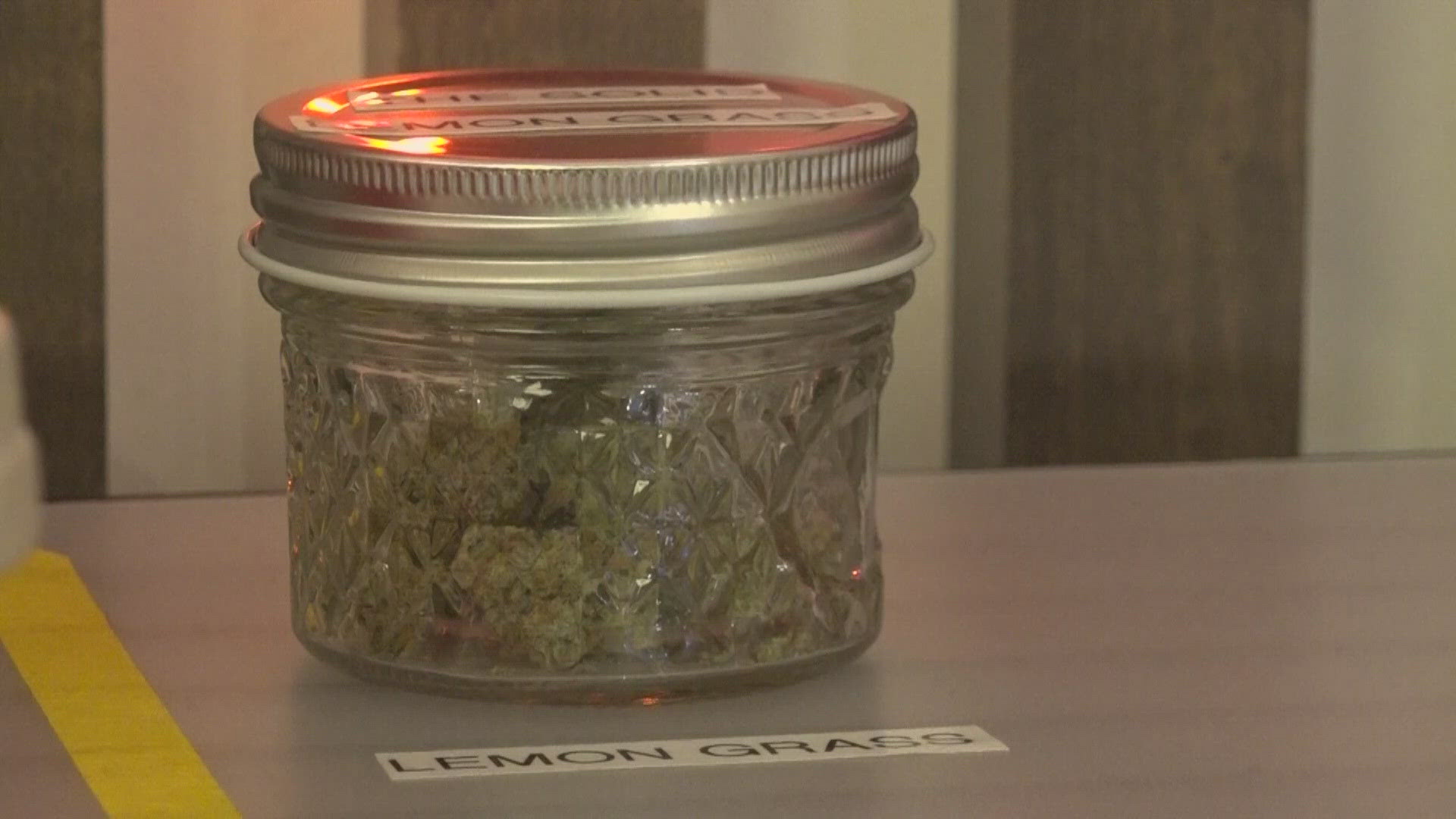

Currently, Delta-8 THC products — including a large variety of drinks that are popular at bars and available at gas stations throughout the state — can be sold in Missouri stores because the intoxicating ingredient is derived from hemp, not marijuana.

Hemp is federally legal.

There’s no state or federal law saying teenagers or children can’t buy them or stores can’t sell them to minors — though some stores and vendors have taken it upon themselves to impose age restrictions of 21 and up.

The legislation would place these products under the same constitutional framework and rules that the marijuana industry must abide by — including an age restriction, labeling and testing requirements and a mandate that products are only sold at licensed dispensaries regulated by the cannabis division within the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services.

However, the state’s rules also currently ban the “chemical conversion” process used to create the majority of hemp-derived THC products.

When asked how many hemp-derived THC products would still be left on Missouri shelves if the legislation passed and this rule was enforced, Moore said the department would have to take a hard look at the “intent” of the law.

“Everyone knows the rules are part of our regulatory framework,” Moore said in an interview with The Independent after the summit. “Does that indicate intent that chemical conversion, at least, remain prohibited?”

Or, she said, it could also be the law’s intent to simply put these products under the same guidelines marijuana products follow, and the state would need to adapt its rules to be able to keep them on the market.

“We don’t really have a position right now about what that would mean in the future,” she said.

Three weeks ago, Krey Distributing Company, the wholesale company for Anheuser Busch, released hemp-derived Delta-9 THC drinks, and it’s already selling them to nearly 120 bars, liquor stores and convenience across the state.

The products aren’t made using a chemical conversion process, so they wouldn’t be banned if the legislation goes into effect. But sales would definitely plummet if they could only be sold in dispensaries, said Steven Busch, the company’s president.

“This legislation would really hurt our business,” Busch said. “It would also limit the business our customers are doing already, and it would also limit consumer choice by forcing consumers to go into a dispensary to buy these products.”

Pushback from both sides

Hemp is often known for being the part of the cannabis plant that doesn’t get people high.

It’s full of CBD, a nonpyschoactive cannabinoid that helps people relax and often found in massage oils and sleep aids.

But much has changed since hemp was taken off the controlled substance list in 2018 by the last U.S. Agriculture Improvement Act, more commonly known as the farm bill.

Now state regulators can barely keep up with the constantly evolving ways that people have found to make intoxicating products from hemp — largely through a chemical process of converting CBD to THC. The market for things like Delta-8 drinks and edibles is one of the fastest growing markets in the country.

The fact that it is legal federally was the basis for St. Louis Democratic Sen. Karla May’s opposition to a bill sponsored by state Sen. Nick Schroer, a Republican from Defiance.

“The feds are not stopping the sale of this product,” May said, during a Senate floor debate last week. “What you’re saying is we need to shut down all the businesses that are currently selling this product and making revenue from this product, and then transfer them to all of the people that have gotten marijuana licenses.”

While May was the most vocal critic in the Senate last week, both Republican and Democratic lawmakers have pushed back on the idea of forcing the hemp industry under the umbrella of DHSS, saying that would allow the “marijuana monopoly” to take over this market given the limited number of licenses for dispensaries available.

After voters passed a constitutional amendment allowing medical marijuana in 2018, competition for licenses became fierce when the state capped the number of applications it would approve — initially issuing 338 licenses to sell, grow and process marijuana.

Widespread reports of irregularities in how applications were scored fueled criticism of the industry and accusations that insiders were building a monopoly. That criticism spilled into the campaign to legalize recreational marijuana in 2022, though the proposal still won voter approval.

Some applicants who didn’t land medical marijuana licenses turned to producing hemp-derived THC products.

May and others have expressed concern that because hemp is federally legal, lumping it in with the regulations of a controlled substance could result in lawsuits.

Schroer told The Independent in December that he’s closely watching the ongoing legal case of Robertsville-based marijuana manufacturer Delta Extraction.

Delta Extraction had its license to manufacture cannabis products revoked in November, months after a massive recall pulled more than 60,000 products off the shelves — which the state says were illegally made with a hemp-derived THC concentrate imported from out of state.

While hemp is federally legal, state regulators argue that once hemp-derived THC comes into the marijuana realm, they can regulate it.

The question currently before the Administrative Hearing Commission is whether or not Missouri regulators have the authority to prohibit licensed companies from infusing Missouri-grown marijuana products with hemp-derived THC.

If the company loses its appeal before the commission, then Delta will continue to fight in court, the company’s attorneys have said.

And Delta will be arguing the state has no authority to regulate hemp products at all.

“The Division of Cannabis Regulation’s authority to regulate is limited to non-hemp marijuana and does not depend on whether it is used to make THC,” Delta’s attorney, Chuck Hatfield, wrote in a recent letter to the state.

Interestingly, one of the processes the state cracked down on Delta for wouldn’t be banned under the Schroer’s bill. Delta was importing THC-A, a cannabinoid that’s extracted from the hemp plant the same way it is with marijuana. It did not go through the banned chemical conversion process, and Moore said the THC-A process would likely be allowed.

However, state rules also require that THC in marijuana products can only be derived from marijuana cultivated by a Missouri-licensed cultivation facility. Most hemp-derived THC is currently brought in from other states.

Cannabis summit

Hemp is often known for being the part of the cannabis plant that doesn’t get people high.

It’s full of CBD, a nonpyschoactive cannabinoid that helps people relax and often found in massage oils and sleep aids.

But much has changed since hemp was taken off the controlled substance list in 2018 by the last U.S. Agriculture Improvement Act, more commonly known as the farm bill.

Now state regulators can barely keep up with the constantly evolving ways that people have found to make intoxicating products from hemp — largely through a chemical process of converting CBD to THC. The market for things like Delta-8 drinks and edibles is one of the fastest growing markets in the country.

The fact that it is legal federally was the basis for St. Louis Democratic Sen. Karla May’s opposition to a bill sponsored by state Sen. Nick Schroer, a Republican from Defiance.

“The feds are not stopping the sale of this product,” May said, during a Senate floor debate last week. “What you’re saying is we need to shut down all the businesses that are currently selling this product and making revenue from this product, and then transfer them to all of the people that have gotten marijuana licenses.”

While May was the most vocal critic in the Senate last week, both Republican and Democratic lawmakers have pushed back on the idea of forcing the hemp industry under the umbrella of DHSS, saying that would allow the “marijuana monopoly” to take over this market given the limited number of licenses for dispensaries available.

After voters passed a constitutional amendment allowing medical marijuana in 2018, competition for licenses became fierce when the state capped the number of applications it would approve — initially issuing 338 licenses to sell, grow and process marijuana.

Widespread reports of irregularities in how applications were scored fueled criticism of the industry and accusations that insiders were building a monopoly. That criticism spilled into the campaign to legalize recreational marijuana in 2022, though the proposal still won voter approval.

Some applicants who didn’t land medical marijuana licenses turned to producing hemp-derived THC products.

May and others have expressed concern that because hemp is federally legal, lumping it in with the regulations of a controlled substance could result in lawsuits.

Schroer told The Independent in December that he’s closely watching the ongoing legal case of Robertsville-based marijuana manufacturer Delta Extraction.

Delta Extraction had its license to manufacture cannabis products revoked in November, months after a massive recall pulled more than 60,000 products off the shelves — which the state says were illegally made with a hemp-derived THC concentrate imported from out of state.

While hemp is federally legal, state regulators argue that once hemp-derived THC comes into the marijuana realm, they can regulate it.

The question currently before the Administrative Hearing Commission is whether or not Missouri regulators have the authority to prohibit licensed companies from infusing Missouri-grown marijuana products with hemp-derived THC.

If the company loses its appeal before the commission, then Delta will continue to fight in court, the company’s attorneys have said.

And Delta will be arguing the state has no authority to regulate hemp products at all.

“The Division of Cannabis Regulation’s authority to regulate is limited to non-hemp marijuana and does not depend on whether it is used to make THC,” Delta’s attorney, Chuck Hatfield, wrote in a recent letter to the state.

Interestingly, one of the processes the state cracked down on Delta for wouldn’t be banned under the Schroer’s bill. Delta was importing THC-A, a cannabinoid that’s extracted from the hemp plant the same way it is with marijuana. It did not go through the banned chemical conversion process, and Moore said the THC-A process would likely be allowed.

However, state rules also require that THC in marijuana products can only be derived from marijuana cultivated by a Missouri-licensed cultivation facility. Most hemp-derived THC is currently brought in from other states.

This story from the Missouri Independent is published on KSDK.com under the Creative Commons license. The Missouri Independent is a nonpartisan, nonprofit news organization covering state government, politics and policy.