CARBONDALE, Ill. — New research from Southern Illinois University found the Mississippi River is three times older than originally thought.

The team of researched was led by Sally Potter-McIntyre.

According to the data they collected, they discovered the Mississippi River began flowing about 70 million years ago, about three times longer than previously thought.

The research even captured the attention of The Smithsonian Magazine. The magazine called the findings 'extraordinary.'

According to an article from SIU, as of 2014, geologists agreed that the Mississippi River began flowing as “recently” as 20 million years ago, keeping in mind that geological time is a bit different than what most of us use. But Potter-McIntyre’s team found evidence the river began flowing more than three times earlier — some 70 million years ago.

So how did they find this out?

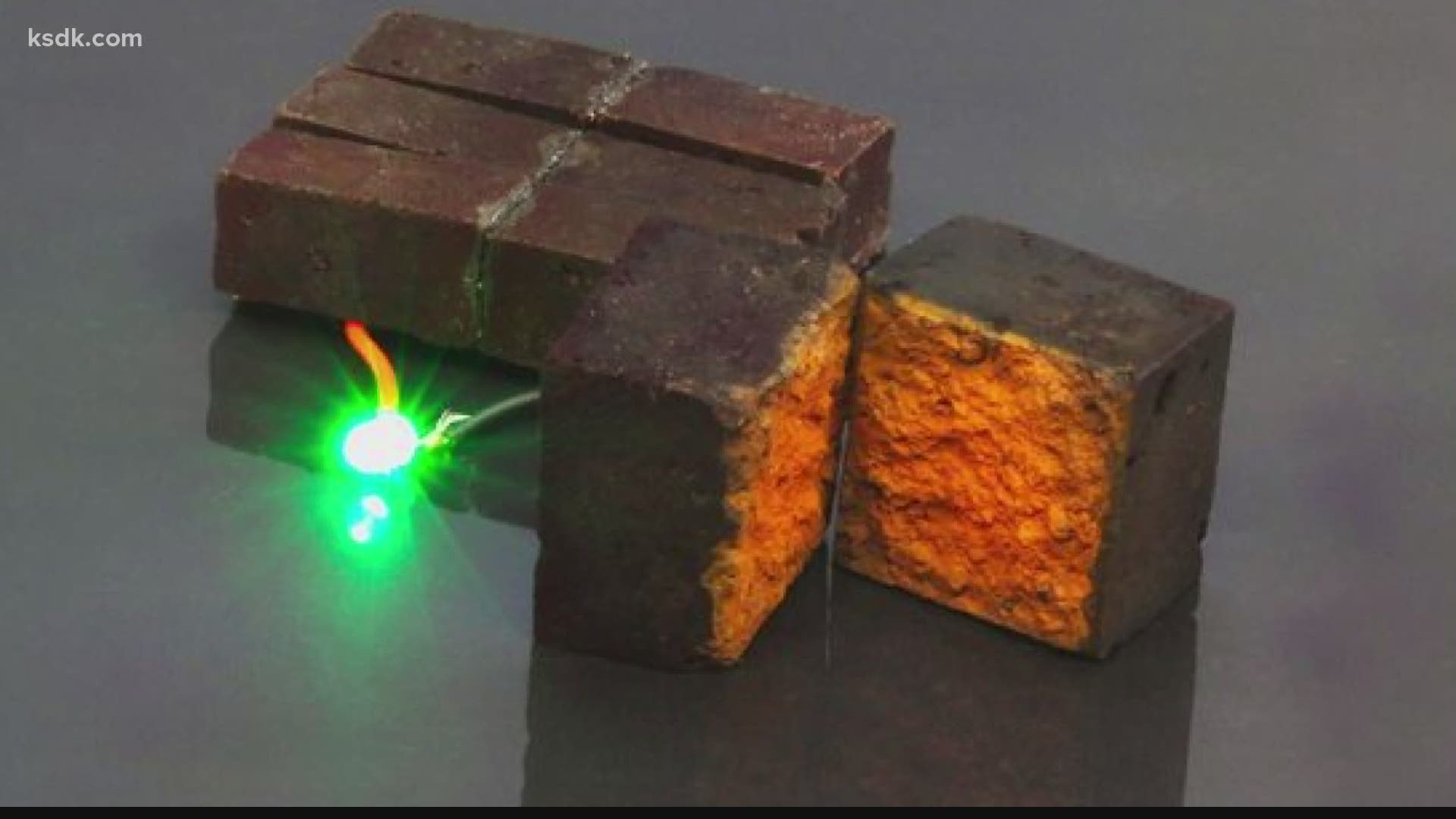

According to the article from SIU, researchers looked at the age of zircon fragments from sandstone found in Southern Illinois. They said zircons are very hard and don't weather away like other minerals and contain uranium that functions as sort of geological clock, said Potter-McIntyre, an associate professor in SIU’s School of Earth Systems and Sustainability.

“The uranium decays to lead at a steady rate that is not affected by chemical reactions, temperature or heat. So, we can measure the amount of uranium and the amount of the daughter product – lead – and determine when that grain was formed,” she said. “If you have zircons that formed recently from, for example, volcanic eruptions, then you can tell the maximum age of the sample. That is what we were originally hoping for.”

One of Potter-McIntyre’s graduate students, Jeremy Breeden, became interested in the Cretaceous deposits found at the most southern tip of Illinois.

The deposits were at least 70 million years old and were unusual because the sediments have never been buried and turned into rocks like other sediments that age, according to the article.

“He was hoping to find some way to refine the age of the deposits in order to better understand the history of the Illinois Basin,” Potter-McIntyre said in the article.

They then visited outcrops of the sediments, collecting gallon bags of sand and then separated the zircons out.

They sent the zircons to the University of Arizona, where there were mounted in epoxy and polished. Team members then used high-tech scanning equipment to measure the isotope decay in the uranium contained in the samples.

“We then compared these results with both published results and some data given to us by co-author Dave Malone from Illinois State University,” Potter-McIntyre said.