JEFFERSON CITY, Mo. — State legislators passed a bill 25 to five Wednesday to allow police officers, firefighters and other public safety workers to live outside the City of St. Louis if they want to work there.

Gov. Mike Parson is expected to sign the bill, which will lift the residency requirement that mandates public safety workers to reside within the city limits for at least the first seven years of their employment.

The issue has been a controversial one for years, as city aldermen have repeatedly struck down efforts by the police union and others to rescind the residency requirement. Opponents have said allowing police officers to live outside the city would give them less of a sense of connection to the city they patrol as well as make the city less safe if officers leave their own communities.

Meanwhile, union leaders and proponents, including Chief John Hayden, have said the requirement hinders the city’s ability to recruit – and retain – officers. Only being able to recruit among city residents limits the department’s ability to fill its 150 or so vacancies, proponents have said.

Repealing the residency requirement has been one of Mayor Lyda Krewson’s priorities.

"Thank you to members of the Missouri House and Senate for finally approving HCS HB 46, which lifts the City's residency requirement for police, fire, and EMS," Krewson said in a statement. "This is a positive step toward leveling the playing field and allowing us to be more competitive in hiring, retaining, and recruiting public safety employees from a larger geographic area.

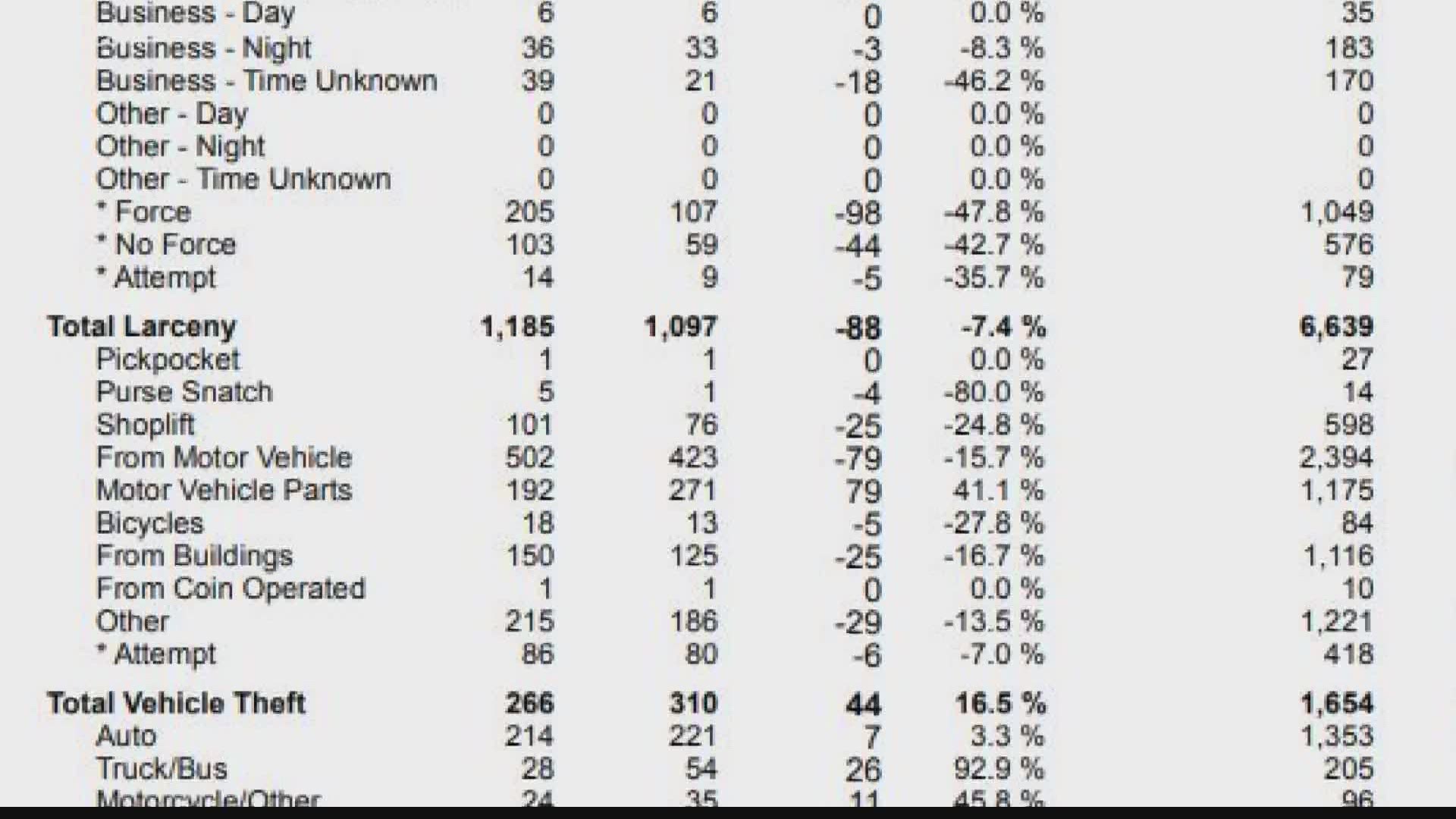

"HCS HB 46 brings the City of St. Louis in line with every other law enforcement agency and jurisdiction in the entire St. Louis region that do not have residency requirements," Krewson said. "It is also one tool we can use to address public safety at a time when the City of St. Louis has already seen more than 180 homicides this year while our police department remains stretched thin by a continued shortage of more than 140 officers."

PREVIOUS COVERAGE: State lawmakers set to repeal 'residency requirement' for St. Louis police despite upcoming city vote

Missouri Attorney General, Eric Schmitt issued a statement, which read, in part: “The St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department will be able to recruit from a wider, more diverse applicant pool, fill empty officer positions, and put more boots on the ground to help curb rising violent crime rates in the City of St. Louis.”

Other attempts to lift the residency requirement at the state level have also failed, as the idea has often been attached to other legislation.

But the measure passed Wednesday during an extra session convened by the governor.

The residency issue has focused mainly on police officers for decades.

Before 1956, prospective officers had to live in the city for a year before they could apply to become a city police officer.

In April of that year, the city's department was facing a shortage of about 150 officers, so officers were allowed to live in the city or St. Louis County.

Then, in May 1973, the St. Louis Board of Police Commissioners required all city police officers to live in the city or move to the city within 90 days of their hiring.

In 2003, the city adopted a rule allowing police, firefighters and other public safety workers to move out of the city after they had worked there for seven years. It's known as the "seven and out rule," said Jay Schroeder, president of the St. Louis Police Officers’ Association.

Now that officers can live where they chose, union leaders expect the number of the city’s officers to increase, Schroeder said.

“I’ve even heard from some guys who said if they do this, ‘I’m back,’” Schroeder said.

Education is the most common reason officers want to live outside the city, as school districts outside the city fair better academically. Others have family who live outside the city they want to be closer to, and some want to decompress away from the city where they work, Schroeder said.

The governor is expected to sign the measure, which includes an emergency clause so it can take effect once he signs it.

Schroeder insists it won’t lead to a blue exodus from the city.