HILLSBORO, Mo. — A crossroads formed in front of Lisa Flamion the day a mentally ill man shot and paralyzed her brother, Ballwin Officer Michael Flamion, from the neck down during a traffic stop:

Stay in the field of mental health, or leave it.

“I kind of felt like, ‘What am I doing in a profession where is this an epic failure? Or can I do something differently and make this more successful for people?’” she asked herself. “And so that's kind of where my drive comes from, just pushing that forward every day.

Lisa holds a question in her mind: "How can I make things better for people so it doesn't escalate to that point where somebody is getting hurt?"

Five years after the shooting, Lisa Flamion is now serving as the first-ever Mental Health Coordinator for the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Department in Missouri. She is in charge of identifying people who could be prone to use-of-force situations due to mental health issues and connecting them with services that could prevent violent encounters with deputies.

And her brother, former Ballwin Officer Mike Flamion, couldn’t be more proud.

“I was stoked, it’s so awesome,” he said of the moment his sister told him about her new job. “It gives law enforcement another resource when we're trying to diffuse the situation when they go to a mental health crisis."

Mike is glad officers will have more tools for these situations.

“But what do you do after that? You can diffuse it and then you send them to the hospital," Mike said. "They might stay for a couple of days and get right back out. And here you are again, doing the same thing over. So now it's a resource. Lisa can step in and maybe examine and see what's going on a little better.”

Mental health help in policing

Lisa Flamion is just the latest mental health professional to join a police department. Police leaders nationwide are seeing the benefit of having civilian mental health workers on the roster.

“People get picked up, they're taken to the hospital, they're kind of this revolving door, hospitals or jails,” Lisa Flamion said. “I want to stop that cycle and get folks the real treatment, the real help that they need to prevent those things from continuing.”

Her brother agrees.

“I think maybe a lot more agencies will see what's going on and start inviting people from the mental health community, the counselors, to come out and assist and work with them and hopefully continue the trend,” he said.

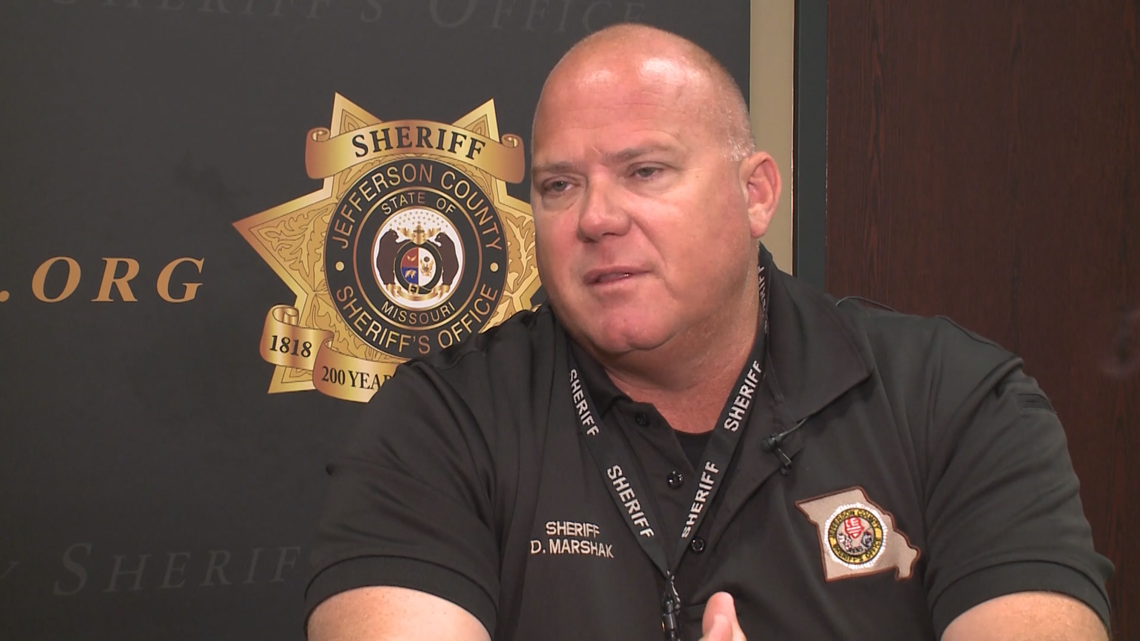

Jefferson County Sheriff David Marshak says it’s hard to measure the effect of the advent of mental health workers alongside the ranks. Lisa Flamion said she plans to keep statistics on how her interventions affect outcomes.

“It's tough to celebrate the negative and the things that didn't happen because we are doing things right on the front end,” Marshak said. “And I think there's many of these types of scenarios in which we do things right on the front end, we get the people the proper help they need, and, as a result, we don't have a crisis or a law enforcement encounter as a result of it.”

Marshak hired Lisa Flamion years after meeting her at a conference.

At the time, she was working for St. Louis County, and wrestling with all that had hit her family, and, in her mind, her profession.

“I really did almost quit counseling,” she said. “It was a struggle. And we were really, I think, just in shock for probably the first year or so.”

She wondered about the tragedy in her life and how she could make a difference.

“There were some very dark days. ‘How do we move forward? How we push out of this?’ And I went through a lot of counseling and I still do. To this day, we'll talk about the experiences I had, especially when I'm in a room full of police officers, because it's important for me to get that message out to them so they can see that yes, these bad things happen. And yes, they are exposed to trauma every day on their jobs. But you can heal from it and you can move forward.”

Mental health professionals in Jefferson County

Marshak said Lisa Flamion fills a void.

“I think the missing component that we've always had is the follow-up,” he said. “There's a number of different times where a subject will have law enforcement encounters frequently. We really need somebody that's a trained professional in that area that goes beyond the scope of law enforcement resources.”

Lisa Flamion is the second mental health professional Marshak has hired to work alongside his deputies.

Joshua White is the Mental Health Coordinator for the Jefferson County Jail. When he was a commander, Marshak oversaw the jail for several years.

"The jails have become the de facto mental health hospitals of our communities," he said. "The reality is we've got a high-risk population in there."

White says the system has a duty to inmates.

"Many of them are dependent upon or have dependency issues. And, for us, we really look for ways to mitigate the risk. We have a responsibility to protect their constitutional rights and to make sure that they have mental health resources in there as well."

White worked in the St. Louis City Justice Center and the Medium Security Institution sometimes known as the Workhouse since 2015 before taking the job in Jefferson County in February 2020.

"There's numerous stories about how Dr. White has helped out inmates in our jail," Marshak said. "He's a rock star."

White said his approach is simple: "They want to hear someone hear their story, make sure they feel like, 'I matter,' even though I'm wearing orange or stripes," White said. "So I just try to build a rapport with them first.

"And then if they're receptive, I try to give them some direction. But ultimately, it's their choice and it's their will to move forward."

He recounted stories of how he interacted with one inmate who was on suicide watch and started spreading feces all over his body and his cell. The man asked to speak with White privately and confessed: "I'm scared. I'm going to jail and I haven't been in there in a while. I've been doing good. And I feel if I have feces all over myself that maybe you guys will think I'm crazy, and send me to the hospital."

White said after further conversation, he got the man an appointment with a doctor to see if medication might help. By the end of their talk, the man told White: "Thanks for not just writing me off like I'm some loon."

"I was trying to get it, you're hurt, you're vulnerable, that's what I'm here for," White said.

Another woman recently threatened to hurt a jail staff member.

"She just wanted her diet changed because she wanted natural food and she knew if she startles you, she'll get a reaction," White explained to the jail staff member after meeting with the woman. "I told her, 'Let me help you find a way to better advocate for yourself."

Marshak said he envisions Lisa Flamion and White working together.

Expanded toolbox for officers

Some activists believe police departments should be defunded in favor of hiring more mental health workers to respond to calls for help. Marshak said he is not a supporter of the defunding movement.

“For us, this isn't about replacing police officers, this is really about enhancing our response to the community,” he said. “And I think that's an important difference for us.”

It’s a resource Mike Flamion said he wishes he would have had when he was an officer.

“There's been numerous times, as I've been on the call where the only thing they do is send them to the hospital because putting them in jail is not the right thing to do," Mike said. "So you take them to the hospital and drop them off, and let them be evaluated. And they go right back out after a few days.”

Lisa Flamion said she believes meeting people in need of mental health services alongside deputies is crucial.

“Letting them get to know me and see that just because I have a deputy with me or I'm from the sheriff's office, nobody's in trouble, we're just here to help,” she said. “That's kind of the biggest hurdle I face is getting people to understand and trust me on that level that I'm not here to take you to jail. I'm not here to take you to the hospital. I'm here to get you some services and get you the help that you need.”

Return to JeffCo

Lisa Flamion, a Jefferson County native, said her new job also makes her feel like her career path has come full circle. She and her brother grew up in High Ridge and graduated from St. Pius High School in Festus.

She went to Jefferson College for her first two years of college while she was working on her master's degree. She completed her internship in the school counseling program at Festus Middle School and at Hillsboro High School.

"This is home," she said.

Jefferson County has between 700 to 800 calls a year involving suicidal subjects.

“I'm really focused on identifying those folks that are high risk, that are putting themselves in situations where there's a potential use-of-force based on their mental health symptoms,” she said. “I want to make sure they stay safe.

“I want to make sure my deputies stay safe. If we can get in and get some interventions in place before it gets to that level, that's kind of where my focus is.”

She said her interventions will look differently depending on the situation.

While heading to work recently, Lisa Flamion said she heard scanner traffic about a deputy talking to a man who was a serial trespasser.

“That's kind of a trigger for me to realize that we maybe need to get some interventions in place for this person before it becomes a level where he's put kind of backed in the corner and is fighting,” she said.

Systemic hurdles for those with mental illnesses

The man who shot her brother was found mentally incompetent to stand trial.

Lisa Flamion said she has often wondered how the system failed him.

“There was some anger, but it was more anger at the system,” Lisa Flamion said. “This man was is obviously very sick.

“And how many interventions had missed or failed for him? How many times had he interacted with the police or how many times had he interacted with the mental health system and here he was still struggling to that level. So that's a lot of where my anger came from, just that that we hadn't been able to help this man before this happened.”

Lisa Flamion keeps a picture of her brother on her desk. It’s a selfie he took in his patrol car, in uniform months before the job he loved changed his life and his family’s forever. He’s smiling and giving a thumbs up to the camera.

Knowing he serves as her inspiration is moving to Mike Flamion.

“It's kind of a deeper emotional thing with it being my sister, to know that something that happened in our family is what inspired her is really neat,” he said.

He’s also found a new calling in mental health awareness.

He and his wife, Sarah, volunteer for a nonprofit called Code 3. As board members, they help oversee the organization that assists first responders critically injured in the line of duty or who have suffered catastrophic life events, such as cancer or off-duty injuries that affect their ability to work

Lisa Flamion is proud of her brother, too.

“For whatever reason, we were given this platform,” Lisa Flamion said. “And I think my brother has handled it very gracefully as well, to be able to push forward and reach out and help other folks who are struggling.”

So far, she's happy with the path she chose at the crossroads.