ST. LOUIS COUNTY, Mo. — St. Louis County Executive Sam Page has shown no proof that COVID-19 is spreading at restaurants and lacks the legal authority to declare indoor dining illegal, according to a class action lawsuit filed Wednesday by about 40 restaurants.

At issue is Page’s Safer At Home Order dated Nov. 12, which states indoor dining is illegal and restaurants could be subject to fines and criminal penalties should they allow it.

In their lawsuit, restaurant owners allege Page, his Acting Health Director Emily Douchette as well as St. Louis County do not have the power to issue such an order, and, by doing so “usurped” the power of the County Council and exercised “absolute executive power that casts fundamental principles of separation of powers to the wind.”

“Defendants view COVID-19 as conferring an unfettered power upon them to regulate private conduct in whatever manner they deem necessary without any procedural, substantive or temporal constraints on their authority,” the lawsuit states. “Defendants are wrong.”

Page’s spokesman, Doug Moore, has told 5 On Your Side he cannot comment on a lawsuit he hasn’t seen. And, the lawsuit was filed shortly before 1 p.m. Wednesday.

But during a press conference Wednesday updating the county's COVID-19 response, Page said he believes restaurants and bars are "part of the way this virus is spreading" based on "the science of how the virus spreads."

He also downplayed the number of restaurants objecting to his shut down order.

"I recognize the how our bars and restaurants are disadvantaged and I recognize their enthusiasm to stand up for their industry," he said. "All industries do that with an enormous amount of passion, as they should, but our public health experts are telling us that now is the time that we should limit the activity of indoor dining-in bars and restaurants.

"What we're seeing is a massive response in the restaurant community of compliance, a massive communication of, 'You're doing the right thing.' We will always have outliers in every business sector and they will sort themselves out and we will deal with it on a case-by-case basis."

In the lawsuit, restaurant owners ask a judge to impose a temporary restraining order on the Safer At Home Order and declare it null and void.

The lawsuit points to a quote the head of Page’s COVID-19 task force, Dr. Alex Garza, made during an October 28 interview with KWMU, in which he stated: “Even if we did shut down restaurants and bars, I don't know how much of an impact that would have on transmission, because there is so much now out in the community.”

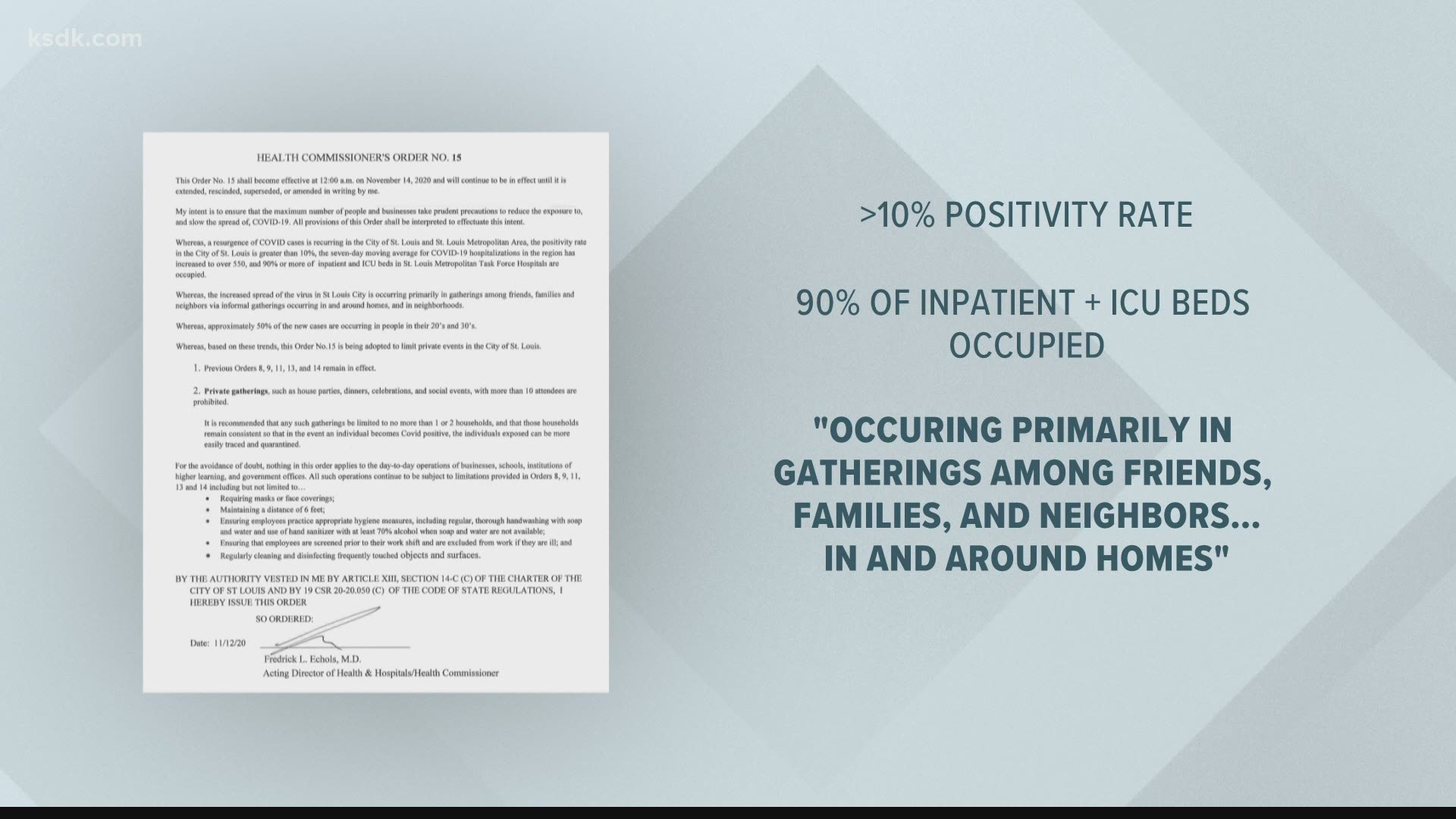

The suit also notes neighboring counties and the City of St. Louis have not shut down indoor dining, which means “restaurants doors away from each other face wildly different rules and restrictions.”

And other places in St. Louis County such as schools, churches, nail salons and malls remain open and casinos or concert halls can open if plans are approved ahead of time.

Restaurants are not given the option to present plans to the county for approval, which the lawsuit alleges is a violation of the Missouri Equal Protection clause.

“Defendants do not point to any instance of COVID-19 spread at plaintiffs’ institutions, whose owners and managers have worked hard to keep their employees and patrons. Instead, defendants prophylactically close the doors to plaintiff’s restaurants, without proper authority, because of their own unstated and undebated (unilateral) thoughts on how to fight the pandemic.”

During his Wednesday briefing, Page hinted that other shut down orders may be coming.

"That's where we're headed," he said. "We are headed past bars and restaurants and we are headed toward a greater shutdown unless we can stop the transmission of this virus in our community and we can get our hands around it."

But if Page wants to shut down restaurants, he can only do so with the permission of the County Council, according to the lawsuit.

The lawsuit points to St. Louis County Ordinance 602.020(3), which authorizes the Director of Health, or the Medical Director, to have “general supervision over the public health, and empowers the director, with approval of the council,” to make rules and regulations to promote or preserve the health of persons in the county.

“This continuing exercise of one-person rule violates the fundamental theory of separation of powers, it violates Missouri non-delegation law, and it violates the plain text of the ordinance,” according to the suit. “No one disputes that the exercise of executive power may be necessary in some time-limited, emergency situations.

“But the defendants’ sweeping assertion that they can rule by emergency powers, in unlimited duration and without any regard for the County Council, exceeds the scope of their statutory authority. This sets an extraordinarily dangerous precedent.”

You can read the full lawsuit in the document below:

The restaurants recommend Page submit his ideas on how to fight the pandemic through the County Council.

“Plaintiffs might not like what happens next, and there may be other battles at that point, but that is what democracy requires and the law says must happen,” according to the lawsuit.

Page didn’t always issue orders via his Acting Health Director. In March, he declared a State of Emergency, which allowed him to avoid the County Council.

The lawsuit called that initial order “flawed.”

St. Louis County Ordinance 703.030 permits the County Executive to declare a state of emergency only “in the event of actual enemy attack upon the United States or of the occurrence of disaster from fire, flood, earthquake, or other natural causes involving imminent peril to lives and property in St. Louis County.”

“COVID-19 is none of these things,” according to the lawsuit.

The lawsuit also alleges the fines and sanctions the order threatens as penalties for those who defy it are without merit because the Missouri Constitution “forbids the Medical Director from issuing orders that subject citizens to fines or imprisonment,” according to the lawsuit.

The suit also alleges the order violates the Missouri Constitution’s guarantees of freedom of assembly and association.

“Rent, mortgage and utility bills will not stop coming while plaintiffs’ restaurants are shut down, and there will be no sales to customers to pay those bills other than from takeout,” according to the lawsuit. “Plaintiffs will have to lay off staff, and ultimately may face permanent closure of their operations.

“Without the opportunity to safely operate their businesses, plaintiffs face an existential threat.”