ST. LOUIS — The next mayor of St. Louis will face the same overwhelming challenge that has haunted the current mayor and many of her predecessors: Violent crime is rampant and efforts to address it have failed.

The city known for its gleaming Gateway Arch is filled with charming neighborhoods, great restaurants, and top-rated hospitals and universities. St. Louis lists a world-class zoo, art museum, science center, symphony orchestra and botanical garden among its many gems.

But the crime is relentless. The St. Louis homicide rate has been among the nation's worst dating to the 1990s. The city reported 262 killings last year, 68 more than in 2019. Seventeen victims were age 17 or younger.

And the crime is taking an economic toll. Block after block of once-stately homes have been left behind in the flight to the suburbs. The city had 856,000 residents in 1950. It has about 300,000 now. Major employer Centene Corp. announced in June it would add thousands of jobs in North Carolina, rather than at its St. Louis County headquarters. CEO Michael Neidorff made it clear that crime has made the company skittish about St. Louis.

The four mayoral candidates offer differing plans to contain the violence, but agree it’s the top priority.

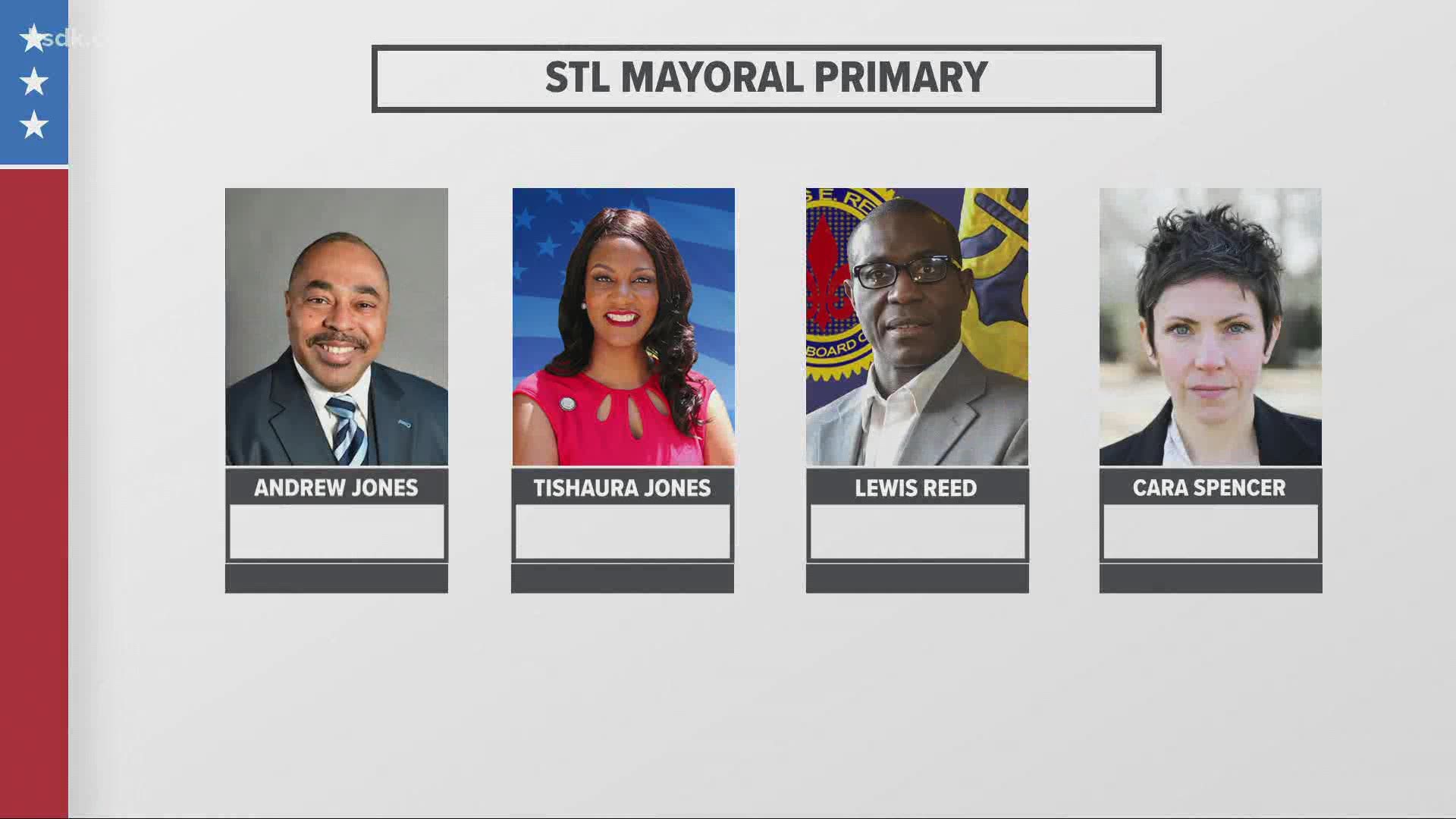

Democrats Tishaura Jones, Lewis Reed and Cara Spencer and Republican Andrew Jones will compete in a primary Tuesday under a new nonpartisan format. The top two vote-getters will move on to the April 6 general election. Incumbent Democrat Lyda Krewson isn’t seeking a second term.

Krewson, 67, was elected to be the city’s first female mayor in 2017. Her husband was killed during an attempted carjacking in 1995, and Krewson campaigned as an anti-crime advocate.

Krewson put her own immediate mark on the police department. Former Chief Sam Dotson abruptly retired on her first day in office in 2017 and she picked department veteran John Hayden as chief. But the violence hasn't abated.

Krewson announced her decision not to seek reelection in November, saying elections “are about the future.” She said at the time that challenges posed by crime, COVID-19 and other issues were not factors in her decision.

Recent St. Louis elections have favored progressive Democrats so Krewson, a self-described moderate, may have faced long reelection odds.

Kim Gardner was elected circuit attorney in 2016 and reduced incarcerations, stopped prosecuting minor crimes such as marijuana possession and frequently butted heads with police. She easily won reelection last year.

Racial justice activist Cori Bush now represents St. Louis in Congress after her stunning defeat of 10-term Rep. William Lacy Clay in the August Democratic primary.

For Reed, the 58-year-old president of the Board of Aldermen, crime is a “personal issue.” His brother, Eugene, 32, was shot to death in 1989 in Joliet, Illinois.

“I know what those families are going through and I don’t want another family to live through that,” Reed said.

Spencer, a 42-year-old alderwoman, picks up bullet casings on her daily jogs. It took only a few months to fill a pint jar.

“I plan on addressing lots of issues but let me be clear: If we don’t address violent crime, nothing else matters,” Spencer said.

Tishaura Jones, 48, the city treasurer and a former state representative, wants to bring in more social workers, mental health counselors and substance abuse counselors, rather than adding more uniformed officers.

“The arrest and incarcerate model of public safety obviously isn’t working," she said. "And in cities where they have added more police to the mix, those cities are no safer than they were before. So we have to do something different.”

Andrew Jones, in contrast, wants more money for police. Jones, 60, a utility executive, said that most killings are connected to drugs and gangs.

“We know these people who are the problem, and it’s only a small population of people who are committing these levels of crimes,” he said. Andrew Jones and Tishaura Jones are not related.

Reed agrees underlying issues such as poverty and mental health must be addressed. He said the city also must do a better job of arresting and convicting violent criminals. Two-thirds of homicides go unsolved, according to the city's police department.

“What I plan to do is focus every available city resource, and leverage state and federal partners, in going after unsolved cases,” Reed said.

Spencer favors a “focused deterrence” model connecting those at risk of committing violence to self-help resources, but making it clear those who cross into crime will face the consequences.

There have been several fatal police shootings of Black suspects in St. Louis in recent years. Spencer and Tishaura Jones said those shootings have shaken public faith in police and made crime-fighting harder.

“When the witnesses and victims of crime don’t trust the police department, they don’t share with them the very vital information our law enforcement agencies need to solve that violence,” Spencer said.

That distrust was seen in demonstrations after a white officer fatally shot Michael Brown, a Black and unarmed 18-year-old, in nearby Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014.

Protests erupted in 2017 after former police officer Jason Stockley, who is white, was acquitted of killing Anthony Lamar Smith, who was Black. During one protest, police arrested more than 100 people, including journalists. Some of those arrested accused police of brutality.

Streets filled with protesters again last summer after George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis. Krewson’s home was the site of demonstrations that prompted her and her husband to temporarily relocate.

Washington University political scientist Betsy Sinclair said the new election format offers hope for a turnaround. She believes candidates are more focused on issues rather than politics, and voters are more engaged.

“I feel like this is a great moment for the city of St. Louis," Sinclair said.