DETROIT — Few American cities understand the struggles of St. Louis better than Detroit.

The Motor City reached its heyday in the 1950s and 1960s as the post-World War II industrial economy roared to new heights, bringing middle-class jobs and wages along with it.

The decades that followed brought crime and corruption, decline and despair.

But sworn officers and civilian analysts working at the Detroit Police Department have made significant progress, rapidly closing the gap in their pursuit to identify and arrest people committing crimes.

The strategies that made that possible could provide a path to improvement in St. Louis.

Live video feeds from cameras installed in highly visible locations all over the Motor City stream high-definition images into a real-time crime center at police headquarters. While surveillance video is hardly revolutionary, the way Detroit markets the program has caught on with companies and consumers alike.

Police Chief James White said officers were taking reports on carbon-copy notepads when he was first sworn in during the mid-1990s.

“The criminals are getting smarter, so we have to be smarter," White said. "Technology is here. You can’t run from it.”

His officers hope their suspects can't escape it either.

“It feels good to catch the bad guy," Assistant Chief David LeValley said.

They've been doing a lot more of that these days because of Project Green Light, a public-private partnership that prioritizes safety and swift police responses around businesses that invest in the camera equipment and internet router.

“We had a lot of carjackings that were occurring at gas stations in the city,” LeValley said.

The city started small in 2016 and arranged for eight gas stations to purchase camera equipment and bright green lights that flashed outside of their stores. The gear belongs to the business, but the video feeds directly to police.

Eight years later, a map of the city of Detroit shows green light cameras have been installed virtually everywhere.

“You look for those (green lights) when you’re going to specific places to stop if they have it," Kaytea Moreno Elst said. "Absolutely, they're safer."

The mayor's office says 866 businesses have invested in the equipment since its inception in 2016. Five years later, the police reported a 44% reduction in carjackings. They attributed the progress to Project Green Light.

The color flashes a warm, inviting signal to customers, and a warning to would-be criminals. Not only are they more likely to get caught, but they're also less likely to fight charges and accept a plea deal, according to the chief.

“Oh my God, I mean it’s a game-changer," the chief said.

For a total price tag of roughly $11 million, the city installed a Real-Time Crime Center where analysts review precision surveillance network to rapidly track suspects in criminal acts. Separate software programs monitor alerts from sensitive sound receptors that feed into the ShotSpotter system.

Captain Matthew Fulgenzi showed us video of one woman police arrested within minutes after she fired off a gunshot outside a gas station.

"In this particular case, we had no 911 call, so without ShotSpotter technology, the police would’ve never been alerted to this location," Fulgenzi said.

Other hidden cameras set up around the city can detect motion or scan license plates. The images flash across a massive video wall in a control room where detectives, dispatchers, and analysts work to crack down on illegal dumping or follow suspects' movements.

“The areas are a lot cleaner, so we’ve got the convictions, we’ve got the arrests, we’ve got less dumping occurring in these areas," LeValley said.

Second Chances

As the city expedites the swift delivery of justice and its consequences, a team of lawyers is writing its redemption story one person at a time from city hall.

“We believe in second chances,” said Shayla McElroy, the community outreach manager at Project Clean Slate. “When you have misdemeanors or felonies on your record, you come across a host of barriers. Specifically, as it comes to employment, housing and educational opportunities.”

Pointing to academic research that shows ex-cons often experience lost wages and a higher risk of repeat offenses, Mayor Mike Duggan's office opened a small office in the city's legal department back in 2016 to start processing expungement applications for former felony convicts who live in the city.

McElroy had just moved back home to Detroit after working in a California jail where she saw the same people coming back to jail as repeat offenders.

“Over and over again. Sometimes, like within a 24-hour time period," she recounted. "And a lot of times, my question was, 'What’s going on? Why do you keep coming back?' And they’re like, 'It’s harder outside than it is in here.'”

Hiring a private attorney to fill out the papers, process fingerprinting with the Michigan State Police and to apply for expungement can cost up to $3,000. The cost barriers are so high, a recent study from the University of Michigan showed only 6.5% of convicted felons pursue expungement within the first five years of their eligibility. Those that do complete the process see an immediate uptick in earning potential. Research shows the average former convict with a felony sees a 22% jump in wages in the first year after expungement.

McElroy refuted any argument that giving someone a clean slate meant the policy was going "soft on crime."

“It’s not soft on crime to set somebody up for success, so they don’t have to return back to a life of crime," she said.

U of M researchers published the first-of-its-kind study examining expungement and recidivism data and found just 2.6% of the people who received an expungement went on to commit a violent crime afterward. Those rates of recidivism are lower than the rates of the population of Michigan as a whole, according to the study.

Demand for a fresh start in Detroit is growing faster than they can manage.

A city budget that started out very small has grown into nearly $1 million per year, bolstered by hundreds of thousands of dollars in grant funds from the U.S. Department of Justice and charities like The Ballmer Group.

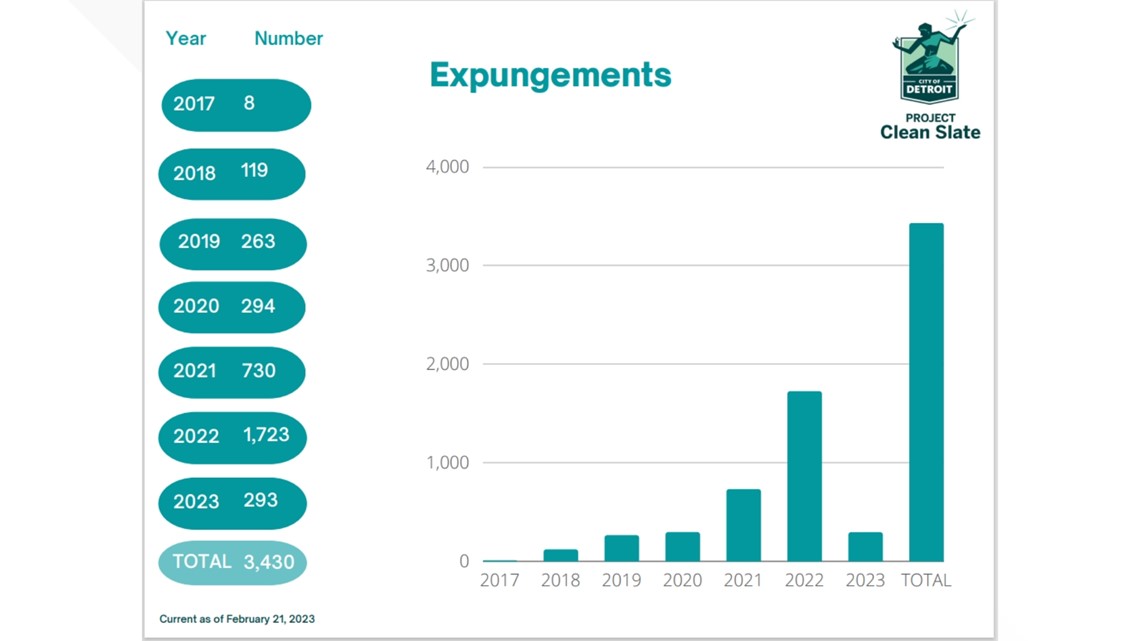

"The first year we had this program going, we got eight expungements," Executive Director Stephani LaBelle said. "Over the years, we’ve really expanded and grown exponentially since 2019."

Last year, they processed 1,723 expungements, and have thousands more applications coming through the pipeline.

For Nick DuBose, expungement came just in time.

“After I got my record clean, the sky’s the limit,” he said with a smile. “I can do anything.”

But for years, DuBose ran into obstacle after obstacle, both in his professional and personal life. He felt that pang of guilt on a trip to Niagara Falls.

“My daughter points across and she’s like ‘Oh Daddy, what’s over there?’ And I was like, ‘Oh, that’s the Canada side.’ And I’m like ‘We’ll go there one day.’”

Except that was a promise he couldn’t keep. Two non-violent felony convictions meant he couldn't cross into Canada.

“Immediately when I said it, I’m just like, ‘Oh…’” he said.

One month after his expungement, an unexpected tragedy struck his family. His 2-year-old nephew suddenly needed a place to live, and very nearly became a ward of the state.

“He literally had no other option," DuBose said. "It was my house or the state.”

Had that felony still been on his record, his family wouldn't be whole today.

"He's living with me now, and so they squared that away," he said. "They vet you for that, though. If I got a felony on my record, my nephew goes to the state.”

DuBose provides for his family at a higher level, too. His clean record unlocked job opportunities he was previously denied. He eventually opened his own trucking company and hauls freight for clients in Michigan and Canada.

“I keep on bumping into these areas that it was just like, 'Oh, I've just never had this available for me before. Clean Slate did that,'” he said.

When it occurred to him that the same government that once branded him a felon had built him a bridge back to a brighter, safer, more rewarding future, he says the emotions were overwhelming.

"When I thought about that, that meant that I had my mayor, his team, Project Clean Slate and the team of lawyers, the Detroit Police that was doing the fingerprinting and all of that stuff, my governor's office, all working with a common goal of this for me.

“There has never been a point in my life where I had that type of team working for me,” he said. “When you think about stuff like that, it really hits you. It’s humbling.”