ST. LOUIS — Lou Brock Jr. was not the only son of Lou Brock nor his first-born child, but he was the first son of the Hall of Fame ballplayer and he bears the man’s name. Perhaps that is why, when offered a chance to talk to him about his father (who passed September 6 at 81), I wanted to start by telling Brock a story about Confucius and his son.

Confucius’ wisdom has survived the ages in books, but he was not a writer. He was a musician and what today we would call a musicologist who made a living advising princes and warlords. He was a political consultant. He was so good at his day job, however, that people wrote down what he said. He attracted students and acolytes who were responsible for the survival of his ideas. Confucius himself focused on keeping alive, in memory and performance, the Odes, the ancient Chinese folk poems that survive as folk songs.

When Confucius died (479 years before the birth of Jesus Christ), the font of wisdom died with him. He lived and died in a deeply patriarchal culture that highly prized sons, so Confucius’ students and acolytes descended on his only son in search of wisdom that the great man must have taught his one and only son.

“Leave me alone,” the son told them. “He was my dad. I didn't follow him around like you did writing down everything he said. We played music together. He was my dad. Leave me alone.”

The students and acolytes would not leave him alone. They continued to seek out the son and pester him. The master must have told his only son something he only told his only son that he never told anyone else, that he never told us. What was it?

Finally, the son gave up, and he told them, “My father always told me: Know the Odes. That is all.” Know the Odes. Know the old songs. That is all.

I told this story to Lou Brock Jr., then I asked him, “Your father must have told you something he only told his son that he never told anyone else, that he never told us. What was it?"

“Wow,” Lou Brock Jr. said. “That’s a beautiful question. I never knew that about Confucius. Thank you for telling me that. That would be something really personal. Let me come back to that.”

What he wanted to talk about, first, was what it was like having a father who was a universally beloved global celebrity. The son was struck by, no matter how many other global celebrities were in the room (or at, say, the opening of a new shopping mall in Indiana), the conversation would always arrive at his father.

“I guess you could call him a star among stars,” his son said. Even the most famous people in the world most preoccupied with the problems of being famous asked Lou Brock how he dealt with being famous. They wanted his life hacks as a famous person.

Lou Brock Jr. grew up watching his father play baseball on television, so he knew his father was famous as surely as he knew that he was his father, but that fact never struck the son harder than when he visited Japan in the 1980s with the University of Southern California football team (Brock played defensive back). Strolling the streets of Tokyo, Brock and some teammates gravitated to the sound of spoken English and ended up visiting with some tourists from the Netherlands. When Brock told them he was from St. Louis, one of the Dutch tourists said, "St. Louis: Anheuser-Busch; Lou Brock.”

“And I’m half-way around the world in Tokyo,” Brock said.

His buddies later goaded him, “Why didn't you tell them you are Lou Brock Jr.?” and Brock replied, “They never would have believed me.”

The unbelievable yet true was a routine feature of life as Lou Brock, senior and junior. As the son warmed up to the interview and we established some trust, I mentioned that in the final years of his father’s life he was surrounded by protests of police violence against Black people. Did his father ever tell him stories about dealing with the police?

“Yes,” Brock said, “though I don't think this is what you are looking for.”

The Chicago Cubs traded Lou Brock to the St. Louis Cardinals (one of Major League Baseball's most notorious trades) in 1964, two months after his namesake first son was born. Lou Brock was then a poorly paid, no-name prospect, and his new team did not provide him with lodgings in St. Louis. He could not afford two homes. Brock was traded to St. Louis on the June 15 trading deadline, and for the rest of the regular season he commuted to home games from Chicago on Interstate 55.

On one of these drives, a man traded to St. Louis for the speed of his legs was pulled over by a police officer for the speed of his automobile. When the cop did not believe this 25-year-old Black man that he was speeding to St. Louis to play baseball for the Cardinals, the cop took him into the station. There, a supervisor actually called the Cardinals, where management vouched for their new left fielder and lead-off hitter and begged the police to get him to St. Louis as fast as they could.

“All of the sudden, he had a police escort going 125 miles per hour the rest of the way to St. Louis,” his son said.

During that game, Brock got on first base and was thrown out stealing second. (In 1964, Brock finished second in the National League with 33 stolen bases, but he led the league in being caught stealing with 15.) When Brock questioned the umpire about the call, the ump said, “Shut up, Brock. This is the second time you got caught speeding today.”

The son exclaimed, “It turned out the cop who pulled over my father was the umpire’s son in law!”

Brock shared no story of police abuse concerning his father, but he suffered through a tremendous amount of racism along his father, who was the son of sharecroppers raised in the Jim Crow South. Brock senior was 8 when Jackie Robinson broke the color line in Major League Baseball, and neither the league nor the nation was desegregated during Brock’s early years in the game.

“Absolutely, my father had to stand up to racism,” Brock said. And not only the routine racism of segregated public facilities and widespread disrespect. “He encountered death threats as a Black man breaking Major League Baseball records,” his son said. (Lou Brock broke most MLB records for stolen bases and remains the career leader in the National League.) Bomb threats were phoned into Busch Stadium. The family was accompanied to the stadium by personal bodyguards. One trailed Brock Jr. to school when he was in elementary school.

Surely, this helps to explain why the other most famous people in the world – Ed McMahon and the Olympic athlete then known as Bruce Jenner were two names that came up – turned to Lou Brock for answers about how to cope with fame.

“Mental toughness,” Brock summarized his father. “Mike Shannon talked about it at his funeral. He was never on the Disabled List for 19 years. That was all mental toughness. That was not only what made him a Hall of Fame baseball player. It also helped him cope with things in a gentlemanly fashion that make other people come unhinged. How he approached baseball was the same way he approached racism.”

He related another life hack from his father that he must have passed onto many other people, famous and not famous, helping them to cope. “One of his business partners asked him one day: What makes a Hall of Famer?” Brock said. “His answer was: You come out of your slumps faster.”

All players slump. Hall of Famers come out of their slumps faster.

By then, the son finally had thought of something he could say in the spirit of Confucius’ son giving an answer to the acolytes who wanted to hear something that the master only had said to the son.

Brock Jr. was in the prized position of being recruited for two sports coming out of Ladue High School in 1982. USC offered him a football scholarship, and the Montreal Expos offered him a contact to play professional baseball. The financial support was better for football at the collegiate level and education was a priority, so in the end he did not follow in his father’s fleet footsteps. His father did not push or persuade him, other than to tell him one thing Lou Brock may have never said to anyone other than his son: “Baseball is a career, but football is a job.”

At that point, I felt that my story was complete, but this is not my story.

“I thought you were going to ask what my father’s greatest accomplishment was,” Brock said.

“For the 56 years I knew my dad, his answer was always: Saying yes to the lord Jesus Christ and the way he grew in Christianity. Please put that in your story. He thought baseball only set him up for his work in Christ's name.”

I felt that was the end of Lou Brock’s story, but his son texted me early the next morning: “Got a dad son Confucius one liner that you may like better. Call me today whenever you can.”

I called him when I could.

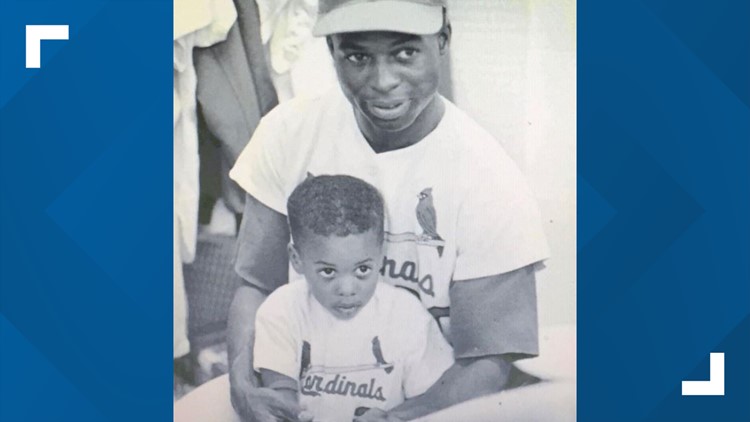

“I was 12 years old at Spring Training with my dad, working as a bat boy in Cardinals uniform for an exhibition game against the Mets, and my dad was the leadoff hitter,” he said – as, indeed, only the son of Lou Brock could say.

“The umpire motioned to me for the number of fresh balls he needed. It was the 1st inning, and I was running the balls out. Then I turned to go back to the dugout, and the Mets pitcher was warming up. I saw this white streak, and the ball hit the catcher's mitt with a big "POW!"

His father, the leadoff hitter, was standing in the on-deck circle.

The son said, “Dad, do you have to play today?”

The son remembered, “He looked at me quizzically and said, ‘Why?’”

The son said, “Because the pitcher is throwing 100 miles per hour.”

The son remembered: “And my dad said, ‘Yeah, well, I swing my bat at 135 miles per hour, so I ain’t worried about that.’”