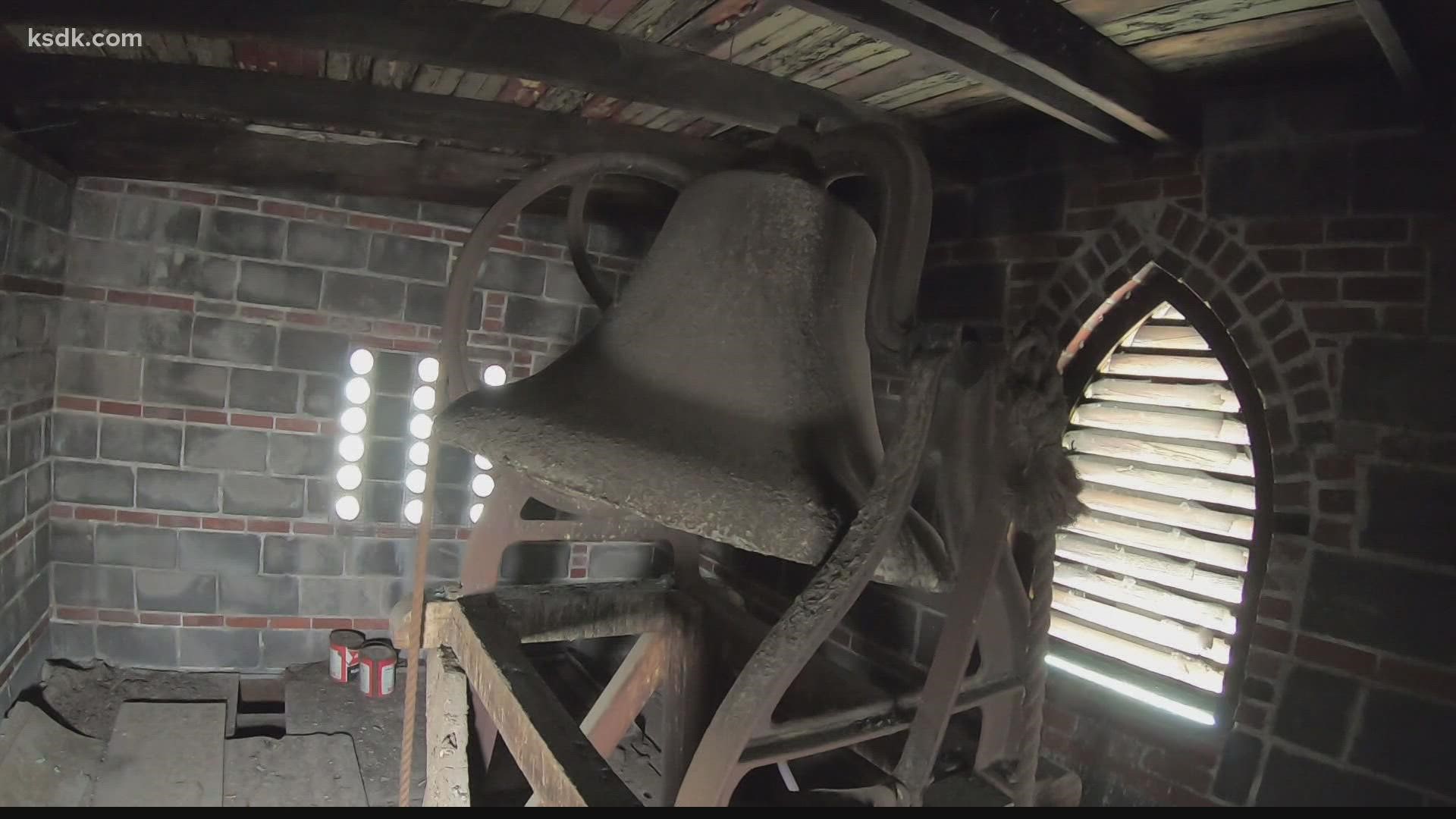

EAST ST. LOUIS, Ill. — The bell at Truelight Baptist church hasn’t been rung in years and still, it’s a beacon of hope for the city.

During “The Great Migration”, six million African-Americans left the deep south in search of better jobs, less racism and a fresh start in northern states. Between 1900 and 1910 the black population in East St. Louis tripled. By 1917, the city was divided, blacks in the south, whites lived up north.

“It had to be most comparable to sitting on a powder keg,” Illinois Appellate Judge Milton Wharton said.

He’s spent years studying the East St. Louis Race Riots.

Tensions over housing, schooling and a changing demographic were simmering. Propaganda against blacks spread; they were blamed for everything from voter fraud to a failed worker strike. On May 27th, a mob made it clear to city leaders they weren't happy with the direction of the city.

“Their aim was to impress upon the mayor this was a white town, we need to keep it a white town,” Wharton said.

For months, groups of whites terrorized and shot up black neighborhoods.

On the night of July 1, a group of black neighbors shot two white men in a car. they turned out to be undercover police officers in an unmarked vehicle. The next day a white mob razed black neighborhoods.

“It didn't matter if you were innocent, it didn't matter if you took no part in it,” Wharton said. “There were babies incinerated in their homes. I guess there was a message that Black Lives didn't matter, even back then.”

The only thing breaking the sound of violence was the bell at Truelight Baptist Church warning the city of danger.

“Just by the ringing of the bell, it symbolizes the church's role in the community,” Wharton said.

Judge Wharton said a mob destroyed, burned and killed while many more stood by idly.

But there were some who stepped in to help.

“There was some prominent white people in 1917 that saved some lives, we need to recognize that too,” Reverend Timothy Chamber said.

Chambers is the third pastor in Truelight Baptist Church’s 112-year history. He believes it’s a story about division, that should bring us together just like it did on the city’s darkest day.

“When you look at it, even now it just kind of takes your breath,” Chambers said. “Like wow, the history right here in this church.”

“The urge for a better life was stronger than the violence that occurred in 1917,” the judge said.

In the 1950s and 1960s, East St. Louis was the fourth largest city in Illinois with a thriving economy and population. Times have changed and through the years the city has suffered the loss of industry, investment and compassion. But the pastor said there’s still hope.

“You have the history, but then you have to look at how we go further,” Chambers said. “I would be lying if I didn't say Truelight needs to rise up and do more. We need to get back to the beacon of the community.”