ST. LOUIS — He had no pulse, no blood, no heartbeat.

He had been getting CPR for at least 12 minutes.

Then, a team of trauma specialists at Barnes Jewish Hospital saw all they needed to know St. Louis Officer Colin Ledbetter wasn’t giving up -- so neither should they, said Dr. Douglas Schuerer, Medical Director for Trauma at Barnes Jewish Hospital and professor of surgery for Washington University.

“We saw him try to take a breath,” Schuerer said.

The 25-year-old and his partner, 28-year-old Officer Nathan Spiess, were shot in the line of duty on Jan. 26 after pursuing a homicide suspect into Ferguson. Spiess took a bullet to his left leg, which he told 5 On Your Side shattered his femur.

Ledbetter was shot just below his vest. The bullet traveled through his groin and severed his femoral artery – which supplies blood to the lower extremities, Schuerer said.

Ledbetter’s family gave permission to the medical professionals who helped save his life permission to speak publicly about his rescue, and the recovery he has begun.

At 1:13 p.m. that day, a call for paramedics echoed inside Christian Northeast Ambulance’s quarters, near Interstate 270 and West Florissant.

Paramedic Robin Robertson and EMT Mark McDonough got into their rig. Their captain, Bryce Schindler, jumped into his emergency SUV.

Before they could get there, a dispatcher disregarded the call.

Six minutes later, another call echoed inside their vehicles. Officers were down at West Florissant and Lang Drive – one mile away from the team.

“It was just by sheer luck that we were in the area already,” Schindler said. “All the pieces kind of fell into place perfectly.”

The ambulance got there in less than three minutes.

“I was about 15 seconds behind the ambulance,” Schindler said. “They were carrying Officer Spiess to the ambulance and when I got out of my vehicle, they were lifting Officer Ledbetter over a fence and carrying him to the ambulance.”

The ambulance was crowded.

Spiess and Ledbetter were in there together along with Robertson and McDonough. A third officer, who was not injured, jumped in. So did Schindler.

“Normally we would have had to wait for another ambulance or one of the fire trucks to get there, who were coming from the firehouse, but luckily we were right down the road,” Schindler said. “My main concern at that time was stopping the bleeding.”

The third officer played a key role too, Schindler said.

“I can't thank him enough,” he said. “I'm not even sure who he was, but he was an extra pair of hands, so he kind of allowed us to do other things while we gave him other tasks to do, like putting pressure on Officer Ledbetter’s wound.

“He was a huge help.”

As the minutes ticked by, Ledbetter’s breathing slowed.

The team put in a breathing tube, and started bagging him. He went into cardiac arrest.

They started CPR – even though his heart had nothing left to pump. They started an IV and pushed fluids and drugs to keep his heart pumping something, at least, Schindler said.

All the while, Schindler said the officers’ radios kept chattering with sounds of fellow officers blocking intersections to let the ambulance get to Barnes Jewish Hospital as fast as possible.

Sirens blared past the ambulance as they raced ahead to the next intersection.

Schindler shouted instructions into a phone to the trauma team waiting at the hospital.

Blood, Schindler told them, lots of it. It was the only thing that could save his life, Schindler said.

“They said they had it ready and they were waiting for us when we got there,” Schindler said.

Only 12 minutes had passed.

“I'll tell you, it felt like a million years,” said Schindler, who is about to mark his 18th year in the profession. “It was one of the longest rides in my life. And I’ve probably taken that ride a thousand times over the years.”

Three teams of trauma specialists were waiting: one for Ledbetter, one for Spiess, and one for the man who shot them, who was shot by a third officer on the scene. That man did not survive.

Schuerer had seen patients in Ledbetter’s condition come into his ER before, whether from shootings, car accidents or other incidents.

“Unfortunately, in our city, it's quite often, and we have a lot of admissions that are this ill,” Schuerer said.

Barnes Jewish Hospital is a level one trauma center, and, in situations like this, Schuerer said it proves crucial.

“Being ready all the time is what a trauma system is,” he said. “You don't necessarily need three trauma surgeons or the E.R. full of people ready all the time, but you never know when.”

Ledbetter needed the system to survive, he said.

“He basically bled out,” Schuerer said. “Most people that have required CPR for as long as he did will not survive.

“And if they do, they usually have a pretty significant neurologic injury due to lack of blood flow or oxygen to the brain.”

But, Ledbetter tried to breathe.

“That’s why we started aggressive therapy,” Schuerer said.

They pumped 25 to 30 units of blood into Ledbetter’s body – enough to replace his total blood volume three times over, Schuerer said.

And they cracked his chest.

“I thank all of the people who have donated blood, because you needed units and units of blood to fill him back up,” Schuerer said. “We put a clamp on his aorta to help increase the blood flow to his brain, and then we were able to manually work on the heart at the same time.”

Meanwhile, Ledbetter’s parents were on their way.

His father, Steve Ledbetter, told 5 On Your Side they were speeding to the hospital from their home in Illinois hoping for – and expecting – to spend some final moments with their son.

Three hours after surgery began, Schuerer finished, and made the solemn walk toward Ledbetter’s family.

“I told them we got him out of that first phase alive, but I really don't know how well he's going to do,” Schuerer said. “And I wasn't very optimistic.”

Then, Ledbetter started defying the odds. He woke up, recognized his family, his fellow officers and his girlfriend.

One week after the shooting, nurses locked their arms in his and helped him into a chair, where he sat up and ate a popsicle.

A few days after that, Ledbetter swatted a blue medical glove someone had blown up like a balloon from side-to-side with his hands – an important sign of his brain recovery, Schuerer said.

“Some people, especially those with significant one-sided brain injury, especially with a trauma, won't be able to connect it,” Schuerer said. “They'll lose tracking as it goes across from one side to the other.

“And this just shows that his brain is functioning pretty well, and he can track with eyes and hands from one hand the other and be able to follow that action. And, to me, that's a great sign that he's able to do that so early. He doesn't show a focal side.”

Schindler, McDonough and Robinson have been keeping up with Ledbetter’s progress on social media, in disbelief that he is the same man who was in the back of their ambulance just weeks ago.

“The fact that he had lost that much blood and has had this miraculous recovery is a miracle,” Schindler said.

On Tuesday, doctors moved Ledbetter out of the ICU, and expect him to begin in-patient rehabilitation.

That will likely last several weeks, Schuerer said.

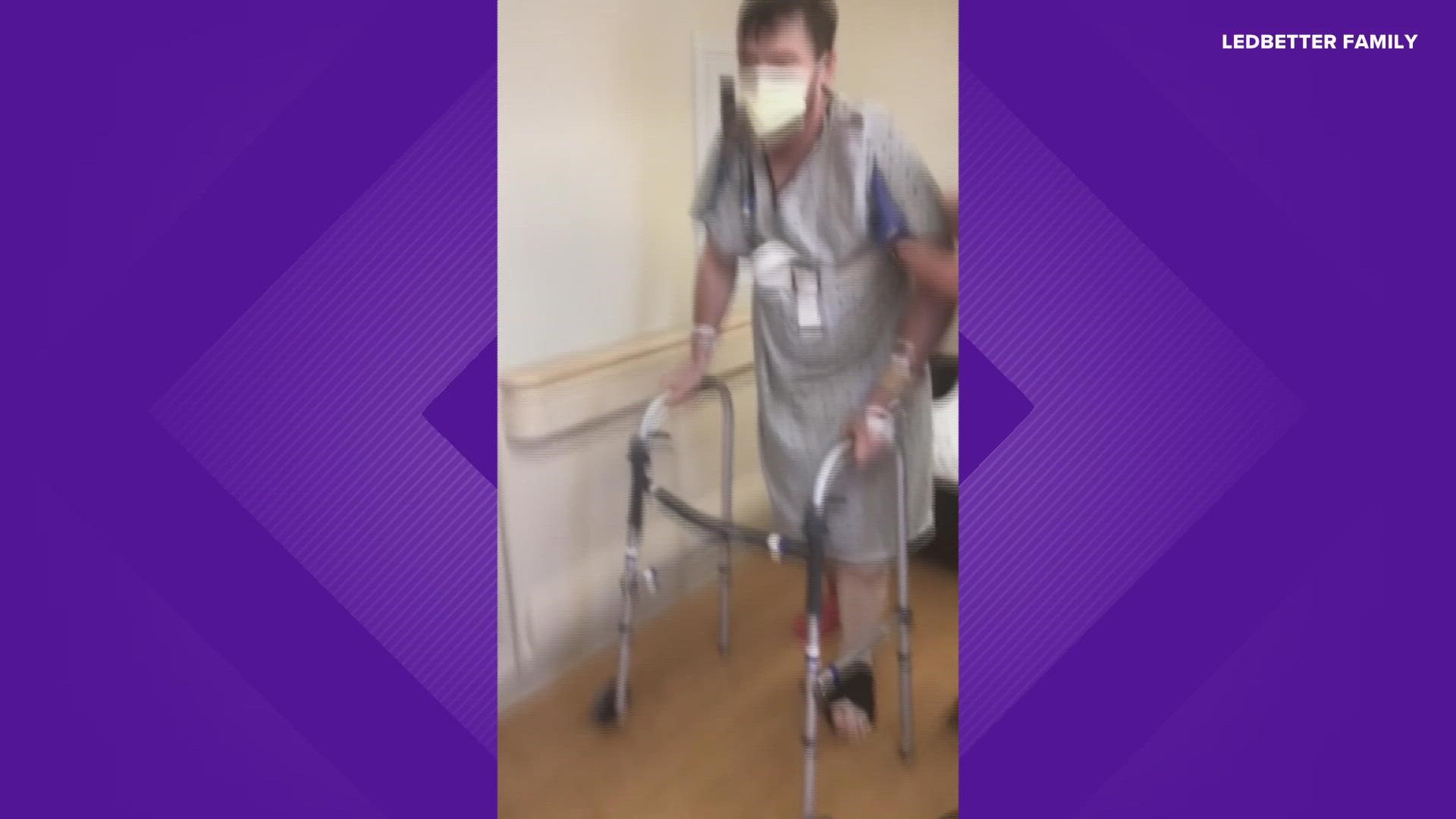

Wednesday he walked the hallways with a walker with a nurse standing beside him and a fellow officer, ever watchful, behind him.

His dad captured the moment on his cellphone.

“Mom’s going to want to see this,” he said.

So does Schuerer.

“Given how quickly he's gotten better here in just a week or two, I would anticipate continued improvement,” Schuerer said. “Long term, hopefully close to baseline.”

Which means close to a full recovery for a man who could only try to take a breath to show the doctor he wasn’t giving up.

Learn about donating blood

Impact Life: https://www.bloodcenter.org/

American Red Cross: https://www.redcross.org/give-blood.html