JEFFERSON CITY, Mo. — Wednesday’s Midwest March for Life at the Missouri Capitol had a different tone this year. It was about fighting.

Nearly two years ago, the crowd celebrated Missouri becoming the first state to ban abortion after Roe V. Wade was overturned. But on Wednesday, a new worry loomed over the annual event: Abortion could soon be enshrined in the Missouri Constitution.

“If God doesn’t intervene in this process,” Paul Shipman, with the Christian radio program Bott Radio Network, said at a rally on the statehouse steps Wednesday, “it just kind of shows you the direction where the nation is going and the direction where the state of Missouri is going.”

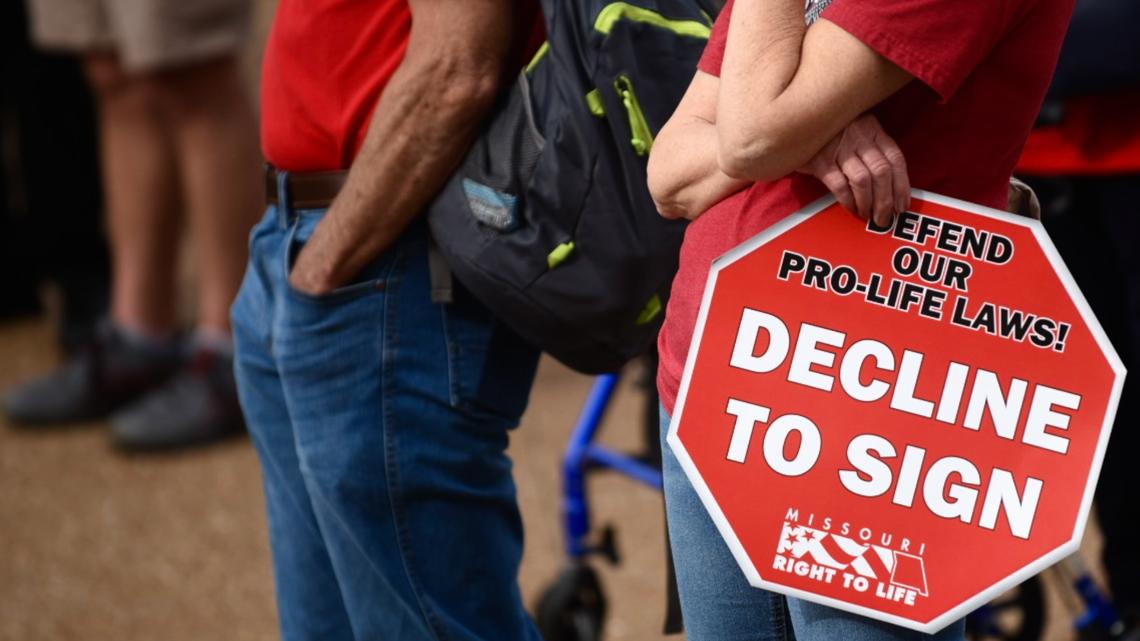

After recent losses in states like Kansas and Ohio, anti-abortion activists say they must take a more aggressive approach in Missouri, using a low-budget grassroots strategy to convince Missourians not to sign the initiative petition that would put a constitutional right to an abortion in the hands of voters.

They enlisted elected officials to publicly decry the ballot measure. They set up a hotline to report the location of signature gatherers so volunteers could show up and hand out “Decline to Sign” materials. And they stoked unsubstantiated fears about the initiative petition process, such as the notion that it could result in widespread identity theft.

And with a Sunday deadline to turn in signatures for proposed initiative petitions, their message and strategy is transforming from “decline to sign” to “withdraw your signature,” with fliers distributed Wednesday hoping to reach those “who regret signing – or who mistakenly signed.”

After signatures are turned in, anti-abortion advocates plan to pour over them to make sure anyone who opts out isn’t counted.

Anti-abortion organizers interviewed by The Independent, both in Missouri and nationally, say the biggest lesson they learned from a series of defeats across the country over the last two years is that they have to engage their supporters earlier in the process.

Missouri could be the first test of the new strategy, even as abortion-rights supporters are raising millions more to get the issue on the November ballot.

“It is the work that is being done on the ground in Missouri that has not happened in any other state across the entire nation,” said Brian Westbrook, CEO of St. Louis-based Coalition Life. “It doesn’t require tens of millions of dollars to get that ground game. That groundwork is already happening.”

Missourians for Constitutional Freedom, the campaign behind the abortion-rights initiative petition, has until Sunday to turn in more than 171,000 signatures from 8% of registered voters across six of Missouri’s eight congressional districts.

Mallory Schwarz, executive director of Abortion Action Missouri, which is a leader in the abortion initiative petition coalition, said she remains confident the campaign will hit its signature goal. She didn’t share where their numbers currently stand ahead of the deadline, but Schwarz said the tactics from the anti-abortion side boost her confidence that abortion is a winning issue.

“If they were confident that people were aligned with them,” she said, “they wouldn’t resort to tactics like blatant lies, disinformation and harassment.”

‘Our track record has not been good’

Anti-abortion groups interviewed by The Independent are focused on communicating three main points to voters: They believe the constitutional amendment goes farther than Roe; they say the amendment would harm health and safety protections for mothers; and they argue it will eliminate parental consent laws.

Abortion-rights groups have said these claims have no merit whatsoever. The decision to move forward with an amendment including viability limit, often considered to be around 24 weeks, rather than no ban at all was considered a compromise position rather than an extreme one.

Susan Klein, executive director with Missouri Right to Life, said her organization has teams across the state who will file requests under the state’s open records laws to obtain copies of all the signatures obtained by Missourians for Constitutional Freedom. They plan to make sure any names she says were scratched out by people who regretted signing are not counted.

Missouri’s messaging is consistent with the strategy being deployed in six other states with abortion measures heading for the ballot, said Kelsey Pritchard, state public affairs director at Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America.

Jamie Morris, executive director of the Missouri Catholic Conference, said the results in other elections made it clear that anti-abortion groups needed a new strategy. The Catholic dioceses in Missouri are helping spread the movement’s message and encouraging parishioners not to sign the abortion-rights petition.

“Our track record has not been good,” he said. “From the pro-life side, we’ve always kind of been used to making one particular argument. And obviously, that was not resonating in some of the other states.”

Morris said the movement isn’t changing its position, but rather it is rethinking its messaging to focus increasingly on mothers as well as the “unborn child.”

“We’ve done a good job of trying to limit the supply of abortions in the state, but what can we do to limit the demand?” Morris said.

In neighboring Kansas in 2022, the Catholic church donated hundreds of thousands of dollars in a failed attempt to pass an amendment that would remove the right to abortion from that state’s constitution.

So far, the Missouri Catholic Conference has been one of the main donors to Missouri Stands with Women, the only campaign focused solely on actively opposing the abortion initiative petition, contributing $5,001.

Morris said Missouri’s dioceses so far have not fundraised on this issue, but if the measure lands on the ballot, he imagines there will be more serious conversations about financial contributions.

Decline to sign

On a recent Saturday in late April, Republican state Sen. Mary Elizabeth Coleman stood outside her hometown library in Arnold and asked constituents not to sign the abortion-rights initiative.

Connie Doty, 74, a longtime Arnold resident and an escort with Abortion Action Missouri, was volunteering to collect signatures that day.

Doty said library staff eventually asked her and the other volunteers to stay on the sidewalk. When Doty stepped into the parking lot at one point to let someone take a picture of the ballot initiative, she says Coleman followed her and told the person in the vehicle not to sign it.

A short time later, after Doty refused to leave for stepping off the sidewalk, she said three police vehicles showed up. They told everyone to “be nice and be safe,” Doty recalls, then left.

Doty said she was not phased, thanks to her decade of experience as an abortion clinic escort encountering protesters who try to stop women from getting abortions. But she said she was alarmed to see her own state senator among the two anti-abortion protesters who showed up.

“Considering that Sen. Coleman was doing this to her constituents,” Doty said, “I found pretty deplorable.”

Doty said despite the interruption, they collected 143 signatures in a couple hours.

“They’re very much afraid that the issue will get on the ballot,” Doty said. “And if it gets on the ballot, people will pass it.”

Coleman could not be reached for comment Wednesday.

Kellie Copeland executive director of Pro-Choice Ohio, said anti-abortion advocates used similar tactics during their 2023 campaign, including instances where police were called on signature collectors.

“Everything about that frankly shows they know that they don’t have the will of the people,” Copeland said. “Why else would they do that?”

A more aggressive strategy

Sam Lee doesn’t want to talk about November. The longtime Missouri anti-abortion lobbyist has his sights set on May 5.

He said other states where anti-abortion groups have taken the approach of only trying to beat abortion measures at the ballot box have lost. That’s why in Missouri, efforts began much earlier.

“The Decline to Sign (strategy) overall has just been more aggressive in Missouri by a variety of groups,” Lee said. “Not just one group or even one church. It is THE strategy.”

Lee said Missouri’s approach has been much more grassroots, spread through social media, sermons and at dining tables.

“Tell your family member not to sign,” he said. “Tell your neighbor not to sign.”

When Lee is asked by some what he’s afraid of, he said it’s simple: “I just don’t think this should be on the ballot. I think it’s wrong. Why should you give people an opportunity to vote for something that is bad?”

Missouri Stands with Women, of which Lee is president, has been distributing messaging, including through paid Facebook ads, encouraging people not to sign.

One in particular depicts a man portrayed in a mugshot offering a pen in his hand. The word “felonies” is in quotes beside the drawing.

“It’s a pretty clever ad, actually,” Lee said. “Is there a guarantee these signatures cannot be duplicated and used for identity theft? Is it a real issue or not? Well I don’t know. It’s been raised elsewhere.”

JoDonn Chaney, a spokesman for the Missouri Secretary of State’s office, said he’s not aware of any threat of identity theft during the signature gathering process at this point. He said the office’s larger focus is ensuring people know and understand what they’re signing.

Lee said his campaign is leaning into a 2005 California law that prohibits the sale or transfer of voter data collected through initiative petitions to other countries after concerns were raised when an initiative petition campaign outsourced signature verification to a firm in India.

So far, Chaney said, the office has received “a handful” of applications to withdraw signatures from the abortion initiative petition.

According to records obtained by The Independent through Missouri’s Sunshine Law, the Secretary of State’s office has received about 140 requests for signature withdrawals from the abortion ballot initiative.

Most did not provide an explanation for why they changed their mind, but one Columbia resident wrote: “I let a very pushy person with a petition make me feel like I needed to sign. Immediately after, all the reasons not to sign flooded my head. Someone needs to speak for the unborn.”

On Wednesday morning, the crowd of at least several hundred people gathered on the front lawn of the Capitol, including many high school students, were encouraged to stall signature gatherers if they encounter them on a sidewalk or at their door in a final push to defeat the measure before it gets to a vote.

Michael Merchant, 31, based in St. Louis and with Students for Life, said it would be easier if the threshold to pass a constitutional amendment was more than a simple majority. Legislation seeking to increase the threshold for amendments to pass through the initiative petition process has cleared the House and Senate, but dysfunction in the Senate has put its chances at risk.

“As much as I like to be optimistic, I’m not 100% confident that we can get 50% (in opposition),” Merchant said. “The main thing we would have to do is convince people that it’s an extreme thing.”

Merchant said he may be able to sway more people who are on the fence by pointing out to them how few limits on abortion would exist under the amendment. Advocates of abortion rights have said limits on abortion access often harm those who are most in need of the procedure, including those with medically-complicated pregnancies.

Missouri Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft, who attended Wednesday’s rally, said he believes his party can defeat an abortion ballot measure whether a higher threshold for passing citizen-led ballot measures is ultimately passed or not.

“I’m not a political consultant,” Ashcroft said, holding an anti-abortion sign at Wednesday’s march. “I just want to make sure that people know what this amendment will actually do. That it’s abortion from conception until the very last second that the last toenail leaves the birth canal.”

This story from the Missouri Independent is published on KSDK.com under the Creative Commons license. The Missouri Independent is a nonpartisan, nonprofit news organization covering state government, politics and policy.