ST. LOUIS — U.S. Rep. Cori Bush is hardly the first politician to take credit for someone else's work, but she may be the most audacious.

For almost the entire duration of her three-plus years in Congress, Rep. Bush (D-Missouri) has claimed credit for bringing home community project funds commonly known as "earmarks."

Some members of Missouri's Congressional delegation, such as Republican Senators Josh Hawley and Eric Schmitt opt to forgo the discretionary pork projects, while Schmitt's predecessor Sen. Roy Blunt was well known for his hustle in bringing home the bacon.

Across the country, members of Congress routinely return home to their districts and cut ribbons, sign giant checks or stage photo ops to demonstrate tangible evidence of their work on The Hill.

In March 2022, Bush joined in the Congressional chorus. In a post online, she boasted bringing home $9 million in federal funding. Later that year, it had doubled to "over $18 million in federal funding."

Last November, Bush's earmarks had grown to $27.4 million. In March, she announced another $13.7 million.

A few days later, she tallied up all the allocations and told her supporters she had secured "more than $41 million in direct funding" for Missouri's first congressional district.

She repeated that total again just last month. She even used taxpayer funds to spread the message with Facebook ads. Then something changed.

Suddenly, an eye-popping claim started showing up on billboards, campaign signs and Facebook ads —some paid for by her campaign; others paid for with federal tax dollars.

"$2,000,000,000+ delivered for St. Louis," one sign read.

The staggering dollar amount had ballooned overnight to more than 50 times larger than all of her previous claims.

"Nothing changed," Bush's communications aide, Marina Chafa, replied. "We’re finally combining it all together."

Around the same time Bush rolled out her inflated claim, her colleague Rep. Jamaal Bowman, an incumbent progressive Democrat, was also testing the limits of political grandstanding. Politico said he was "really reaching" when he attempted to claim credit for more than $1 billion in federal funding for his district in New York.

Bowman's claim, like Bush's, relied heavily on federal grant funds, most of which he had "little to nothing to do with," according to Politico.

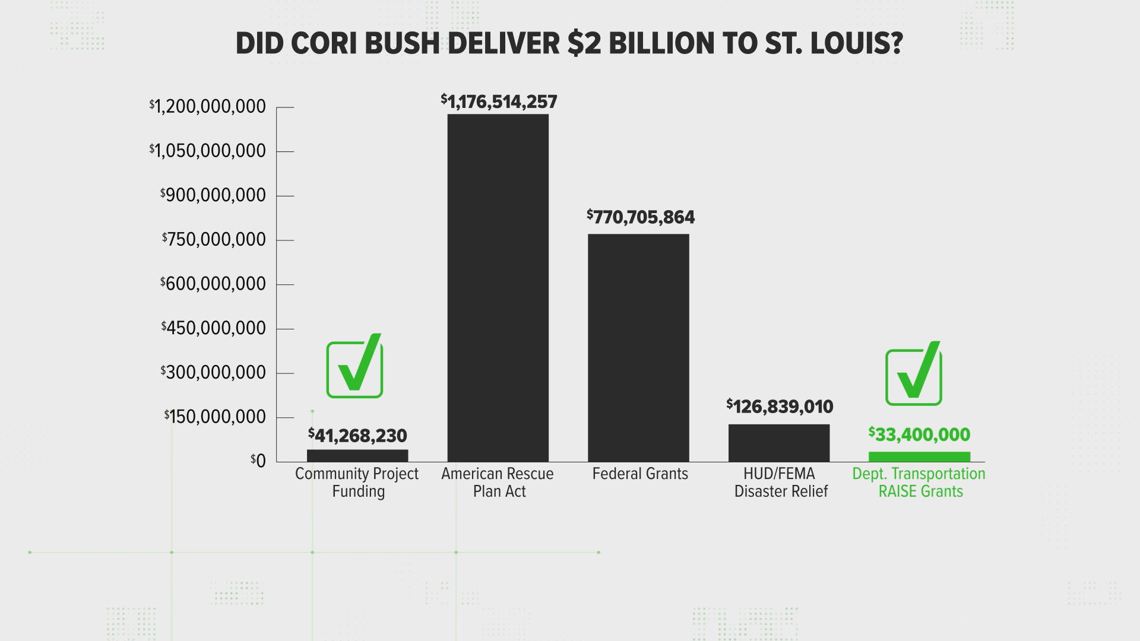

One month ago, 5 On Your Side reached out to Bush's office to ask how it arrived at that number. It sent a "snapshot" document that included five major funding categories, along with generic line item subcategories and a disclaimer that "funding totals change on a daily basis."

5 On Your Side was able to verify some of the smaller funding categories on Bush's initial list. For example, the $41,268,230 in traditional earmarks was properly accounted for.

A fraction of Bush's $2 billion claim also relies on $33.4 million in Department of Transportation RAISE grants. The Brickline Greenway Project was awarded $15.2 million and the West Florissant Avenue Great Streets Project won $18.2 million back in 2021 during Bush's first year on the job.

Blunt also helped to advocate for those funds at the time. Blunt and Bush both wrote letters of support to advocate for the project.

This claim requires some more context, however.

While the funds were appropriated under an old budget, the money hasn't technically arrived in the district yet.

"When you finish your construction, you send in your receipts and they pay for it at that time," Emma Klues, vice president of outreach for Great Rivers Greenway, said in a phone call. "It’s pretty common that you would win the award and then not use the money for years. The money just doesn’t come through until construction."

The project is slated to break ground next year. RAISE grants are now funded under the bipartisan infrastructure program that Bush voted against, but because this specific project was funded before that controversial vote, we can verify that she did help to deliver those funds.

In another instance, Bush's office lists almost $27.7 million for Bi-State Development, the agency that oversees Metro Transit, from Housing and Urban Development and Federal Emergency Management Agency funding. That claim relies on bad math and political spin.

The error is right there in the name. Funds for the "bi-state" are shared between Missouri and Illinois, not just for her district.

"Bi-State, the headquarters itself, is located in our district," Chafa clarified. "The way they get money is from us. I understand they serve others."

Further, Bush is also claiming credit in campaign materials for federal disaster relief funds, which first require a disaster, then a presidential declaration. Members of Congress do play a role in advocating for relief funds but rarely take sole credit for it.

"It’s not saying we and we alone did this. We would never say this," Chafa said. "Among this $2 billion, the congresswoman played a role."

Bush's draft list also claimed credit for $770,705,864 in federal grant awards for generic categories like "agriculture," "arts and culture" or "environmental and energy." Her office declined to provide any additional details.

Weeks later, Chafa and the congresswoman's chief of staff, Lynese Wallace, eventually agreed to meet in person to discuss our reporting. While they still refused to hand over specific line-item details, they did agree to review each grant line by line on their laptops.

Within the first few minutes of reviewing their list of federal grants, we started to spot duplicate entries that artificially inflated the bottom line totals. They deleted the errant entries and allowed us to take notes detailing the rest.

We reconstructed that list and found it added up to be $411,241,077, a lot smaller than the initial claim.

Upon closer inspection, only $208,773,512 had actually arrived in the district. The remainder could still be delivered at a later date.

"The duplicates is just an error on my end, but it doesn’t change the number because we have others," Chafa said. She added Bush's office intends to publish a new revised list on Tuesday morning that will show a full accounting to support the $2 billion claim, though it no longer includes $770 million in federal grant funds.

"It was never the final thing," Chafa said. "The over $2 billion hasn’t changed. It’s the makeup of it."

Some of the federal grant funds Bush's office included in their initial tabulation originated in 1994. Others began in 2001 or 2002, decades before Bush arrived in Washington, D.C.

"We could’ve pushed to discontinue those funds," Chafa said. In their view, because Bush voted to continue them, she's entitled to claim credit for them.

The bulk of the federal grants were research funds awarded to the top universities in the region like Washington University and Saint Louis University. Those pots of money were allocated by federal agencies like the Department of Education, Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy.

While it's technically true that Bush voted to approve federal budgets that steered money towards those agencies, when she voted to approve the spending, she would've had no way to know for sure which universities in her district might one day line up to apply for the funds or which ones might win the funding awards.

Many of the grant recipients were also surprised to hear Bush was claiming credit for the work they had done to procure federal funding.

Before he became a St. Louis alderman in 2023, Michael Browning (D-9th Ward) worked as a grant administrator at Washington University and helped to write some of the very grant applications Bush now takes credit for.

Browning and his colleagues "never had any contact with congresspeople or senators," he said. "At no point did these funds require letters of recommendation from members of Congress and that’s not something that we would ever handle."

He described a mundane process where a grant administrator would discuss grant renewals with scientists and they would determine how much more federal funding was required to complete a research project.

"The application process is very much centered on the scientist," Browning said. "There's no interaction between elected officials."

Bush's office pushed back on that characterization and insisted that representatives are often approached by industry lobbyists or special interests who ask them for support in the budget so that their clients' research can continue.

"Roy Blunt was well-known for getting lots of money from (the National Institutes of Health)," Browning conceded, "but he would lobby in general to fund NIH, and then that funding would 'find its way' to St. Louis because of its availability."

One Capitol Hill staffer who became familiar with federal budgets and grant funding allocations in Missouri said members of Congress started to look for creative ways to line those funds up for entities in their districts after earmarks went away.

"It became very difficult to direct funding back to your district," said the staffer, who requested anonymity to discuss a sensitive subject.

Some of the other totals also seemed off.

For example, under the American Rescue Plan Act, Bush's office claimed a clean, round number of $197,000,000 for the child tax credit. Weeks later, we learned they borrowed that figure from an internal House estimate, which appears to take approximate Census bureau population totals and multiply them by the dollar amount of the tax credit.

However, more precise data is available from the Internal Revenue Service. Some wealthier families did not qualify for that benefit; others might not have claimed it at all. The IRS data showed $155.6 million for the child tax credit in Missouri's first congressional district, a discrepancy of $41.4 million.

"If you don't advocate for these things, they don't happen," Chafa said.

Bush was hardly the lone politician advocating for them.

Before Congress could pass the American Rescue Plan Act, American voters had to elect a president who promised to pass it, then Georgia voters had to elect two Democrats to the Senate so they could send the plan to the President's desk. And before any of that, a global pandemic rocked the world's leading economies, snarled supply chains and zapped local governments of the sales tax bases they relied on.

"Cori Bush has never been someone to say she’s done anything alone," Chafa replied. "Yes, that involved working with a bunch of people. That’s politics."

Bush voted to approve the American Rescue Plan Act on March 10, 2021, two months after swearing the oath of office in her freshman term. Only once she faced the threat of a well-funded Democratic challenger did she begin to claim credit for all of the funding that arrived in her district because of it.

"We fought for certain things to be included," Chafa said.

The bulk of those funds were not unique to St. Louis, nor were the specific funding decisions steered by her office. Instead, they were made by local elected officials, school boards and public health departments. While the $1.1 billion she claims credit for has been set aside for the region, it has not all yet been "delivered," as her billboard claims. More than half of the $498 million intended for the city of St. Louis has not yet been spent.

At a recent press event, Bush acknowledged to reporters that she was worried some of St. Louis County's $193 million in ARPA funding might expire at the end of next year and be reclaimed by the federal government.

One member of Congress, a Republican, texted, "That is some crazy accounting."

Another, a Democrat, joked, "I'd better start hustling."

“In theory, we could be claiming credit for every single dollar that came in," Chafa insisted.

Underlying all of this rhetoric is some perspective: every penny of these funds belonged to federal taxpayers to begin with.

According to the IRS, taxpayers in the first congressional district payed a total of $5.3 billion to the federal government in 2021 alone. Over the course of Bush's career in Congress, that total tax bill likely accumulated to more than $20 billion.