Walking into Total Wine stores in Missouri this summer, it was impossible not to see the display for hemp-derived THC infused beverages.

Total Wine, the country’s largest liquor retailer, set the tone for the alcohol industry in June when it began carrying the products at its seven Missouri stores.

“It has been amazing for us,” said Joshua Grigaitis, owner of St. Louis-based Mighty Kind Co., which makes various kinds of hemp seltzers. “When somebody like Total Wine comes on board, it helps the conversation along greatly.”

Hemp naturally has very little THC, the intoxicating component mostly associated with marijuana. But that potency can be increased with some science.

Now Mighty Kind and other similar products that contain low levels of THC have quickly become new revenue for bars, liquor stores and distributors statewide. These beverages are allowed to be sold in Missouri outside of licensed cannabis dispensaries because the 2018 Farm Bill legalized hemp.

Grigaitis said in some bars, his products make up 40-50% of their sales.

But that all may come to a halt after Gov. Mike Parson signed an executive order on Aug. 1 banning intoxicating hemp products and threatening penalties to any establishment with a Missouri liquor license or that sells food products for selling them. It also bans companies like Mighty Kind from producing hemp-derived THC beverages in Missouri.

The order takes effect Sept. 1. Details of how it will be enforced will be outlined in the emergency rules that are still being written.

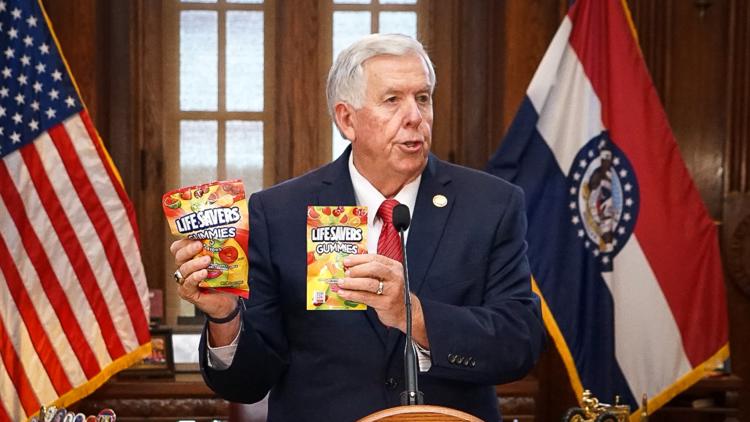

The hemp industry is calling the action an “overreach,” but Parson said at a press conference earlier this month that the main target of his order is companies that produce intoxicating hemp edibles that could be mistaken by children as candy.

Standing alongside Attorney General Andrew Bailey and other officials in his administration at his Capitol press conference, Parson displayed a Lifesavers package that contained THC gummies.

“These companies and these people that are profiting off of this type of material to give it to our children need to stop,” Parson said. “And no excuses. If they want to do it, do it the right way… like everybody else has to do.”

The “everyone else” Parson was referring to was the dispensaries licensed to sell adult-use recreational marijuana. Because hemp isn’t a controlled substance like marijuana, there are currently no federal or state standards to regulate intoxicating hemp-derived compounds, he said.

Parson did not address the fact that about 9,000 retailers statewide are currently selling hemp-derived beverages and edibles, a number that the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services estimated in a fiscal analysis in April.

“That’s a big hit to just make an executive order without any kind of voting or legislation,” Grigaitis said.

Steven Busch, owner of Krey Distributing, said everyone in the hemp industry agrees that those bad actors that Parson mentioned should be taken off the shelves.

But the governor failing to address the impact it would have on thousands of bars, liquor stores and grocery stores was “disingenuous” and “bordering unethical,” said Busch, whose company distributes 11 different hemp beverages in eastern Missouri.

“This executive order singled out any retailers that have a liquor license and said that they cannot sell the products,” Busch said. “So that’s pretty much all of my customers that are currently selling.”

Since March, Busch has led an effort to establish regulations for beverages and edibles by working with various lawmakers to write legislation. It’s set to be filed in December.

For the last two years, the marijuana-industry — which has been a major political donor to both Parson and Bailey — has led an unsuccessful effort to convince the legislature to ban hemp-derived THC products outright.

Grigaitis says he doesn’t believe the order will have the impact the governor is hoping for.

Under federal law, the governor cannot punish people for consuming the products, and Parson was careful to make that point during his press conference. The order only punishes retailers regulated by the state to sell alcohol or food.

Licensed cannabis dispensaries can’t sell these products either because the hemp used to make them has to be grown in Missouri and processed in licensed cultivation and manufacturing facilities – just as marijuana is. Nearly all of these products currently on the market are made from hemp grown in other states.

The order does, however, allow for Missourians to buy these products online from out-of-state companies.

“This is literally forcing everything out of the hands of the people that we have determined or given the licenses,” Grigaitis said. “Why would we take it out of that and put it into the dark? There’s no sense there.”

The response

There will be a response from the hemp industry on various fronts, Busch said. Immediately, he said he will begin circulating the proposed legislation in the hopes of gaining support from lawmakers.

Chuck Hatfield, a longtime Jefferson City attorney who has represented cannabis companies, said it’s “very unusual” for the governor to issue an executive order to do what lawmakers have declined to do for the past two years.

“There will be lawsuits over this, no doubt about it,” Hatfield said, “because it’s an aggressive regulatory strategy and it’s a little bit unprecedented. There are plenty of lawyers out there who are going to advise the industry that they have legitimate legal arguments to make.”

Hatfield believes the matter will be solved in the courts. But any legal action will have to wait until the emergency rules are released, Hatfield said, which will show the true impact of the law.

The emergency rules will be available before the Sept. 1 effective date, said Mike O’Connell, spokesman for the Missouri Division of Alcohol and Tobacco Control – the agency tasked with drafting the rules.

“Anything before we see those rules is kind of guessing,” Hatfield said.

While it is shocking, Grigaitis said he’s not overly concerned about the order.

“I’m pretty good at thriving in chaos,” he said. “The very weekend that we launched our first CBD seltzer into the world was the same weekend that the shutdown happened and the whole world stopped.”

Several of his products contain only CBD, which is a non-psychoactive compound of the cannabis plant and isn’t banned under the order. So the order doesn’t wipe out all of his “alcohol alternative” products completely, he said.

But moreso, he believes Missouri’s industry will garner national support because other states don’t want their governors to take similar actions.

“Everyone in the industry thinks it’s going to be stopped,” he said. “The rest of the country does not want to see this precedent set, where it could then snowball.”

Is it safe?

DHSS director Paula Nicholson warned families about the fact that these hemp products on the shelves are not regulated by any state or federal authority during the Aug. 1 press conference. So there’s no way to ensure they’re safe, she said.

“We have seen the negative impacts first hand,” she said. “Disturbingly, children in Missouri and across the nation have been hospitalized after ingesting these substances. This is unacceptable.”

Julie Weber, director of the Missouri Poison Center at SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital, told The Independent last year that more poison cases had been reported for edibles containing marijuana than the hemp-derived compounds, such as Delta-8.

In 2022, there were 25 cases for Delta-8 edibles for all ages, she said, compared to 125 cases for regulated marijuana edibles for only children 5 years old and under.

However, in a legislative committee in January, Weber testified that the center’s concern for Delta-8 products was increasing.

“It’s the packaging as well that’s a big concern,” Weber said at the time. “It’s attractive, has bright colors, mimics foods and candy. It also has cartoon figures on there.”

Products that mimic trademarked products meant for children are highly condemned by the hemp industry, said Justin Journay, CEO of Indianapolis-based 3CHI, which sells products in Missouri.

“Everybody hates those guys,” Journay said. “Nobody wants to see those guys in business because we get mixed up with them as if we’re the same.”

Busch, who’s company has been a major distributor for Anheuser Busch and other beer brands for decades, said he thoroughly vets the products he distributes – ensuring that they all have gone through third-party testing similar to marijuana products.

And his customers – more than 200 liquor stores, bars and restaurants – treat these products just like alcohol, incentivizing their employees to “age gate,” he said, to prevent underage consumption.

Brian Dix started his own distribution company, Craft Republic, in 2017 that specializes in craft beers and is based in St. Louis. He made the leap to start his own business after spending over 20 years in the beer industry.

One of his fast-growing products is Mighty Kind beverages – and it’s been a big reason why he’s been able to grow his business, he said.

The governor’s order was shocking, he said

“It’s an immediate stop to a significant revenue stream for our business,” Dix said. “More and more people are bringing this category on. So yes, it’s a significant impact that’s got me scrambling trying to figure out what to do.”

Like Busch, Dix ensures that testing is not only done but that results are easily accessible to consumers for the products he distributes.

And like his colleagues, Dix has advocated for better regulations in this space.

“The governor’s office took a very aggressive stance on this,” he said. “And I understand let’s keep the kids safe, but is that really what he’s doing here? Let’s get regulations in place. Let’s get whatever testing requirements. Let’s enable the state to receive taxation and licensing fees and regulate it like alcohol.”

This story from the Missouri Independent is published on KSDK.com under the Creative Commons license. The Missouri Independent is a nonpartisan, nonprofit news organization covering state government, politics and policy.